Apr 25, 2024

Apr 25, 2024

by H.N. Bali

Continued from “Gravest Fault Line of our Polity”

Unresolved Military-Civil Equation – Part II

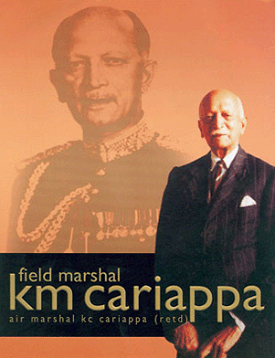

On Gen. Roy Bucher’s retirement, K. M. Cariappa took over as the first Indian C-in-C. A great honor indeed! He also shares another distinction with the Father of the Nation to have maximum number of roads and townships in the country named after him. (There are in all likelihood some half a dozen roads named after the General in metropolitan Delhi area itself.)

On Gen. Roy Bucher’s retirement, K. M. Cariappa took over as the first Indian C-in-C. A great honor indeed! He also shares another distinction with the Father of the Nation to have maximum number of roads and townships in the country named after him. (There are in all likelihood some half a dozen roads named after the General in metropolitan Delhi area itself.)

Before a brief assessment of Cariappa as the Army chief and his role in evolving a working civil-military equation, may I share with you a story I heard from an Army Commander about how he emerged at the top.

A meeting, presided over by Nehru, was organized soon after Independence to select the first future General of Indian Army. Thinking aloud the Prime Minister said: “I think we should appoint a British officer as a General of Indian Army as we don't have enough experience to lead the same.” (Possibly, it was a recommendation of Edwina!) Everybody seemed to support what Nehru said but one of the army officers had the courage to speak out his mind. “I have a point, Sir.” Nehru said condescendingly, “Yes, gentleman. You are free to speak.” He asserted, “You see, Sir, we don't have enough experience to lead a nation too, so shouldn't we appoint a British as India’s first PM?” There was stifling silence when a few seconds appeared to be a millennium.

Then, Nehru shot back, “Are you ready to be the first General of Indian Army?” He got the golden chance to accept the offer but he declined and said, “Sir, we have a very talented army officer, my senior Mr. Cariappa, who is the most deserving among us.”

The army officer who had the courage to counter suggest against the PM’s wishes was Lt General Nathu Singh Rathore, the first Lt. General of the Indian Army. Thus, Cariappa was appointed as the Deputy Chief of the General Staff with the rank of Major General.

Plea for Apolitical Role

To begin with, Cariappa restricted himself to military matters. However, as he grew into the job he began to offer his views on such questions as India’s preferred model of economic development. Nehru had to advise him not to play the role of a semi-political leader. Fortunately, the message sunk home.

When Cariappa demitted office in January 1953, in his farewell speech he ‘exhorted soldiers to give a wide berth to politics’. “The army’s job”, he said, “was not to meddle in politics but to give unstinted loyalty to the elected Government.”

This prompted Gen Sam Manekshaw to say authoritatively in his inaugural Cariappa Memorial lecture on Leadership in the 21st Century that Cariappa “taught the Indian Army to be completely apolitical. Ours is one country, where soldiers have kept out of politics. I think that was the biggest achievement of Field Marshal Cariappa, the greatest service to this country.”

Nehru in his life-time wasn’t too sure of Cariappa’s commitment to an unequivocally apolitical role of the military. He felt that the General was a loose cannon, who could not be completely trusted. Within three months of his retirement, Nehru appointed Cariappa as High Commissioner to Australia. The General wasn’t too happy. In fact, he told the prime minister, “by going away from home to the other end of the world for whatever period you want me in Australia, I shall be depriving myself of being in continuous and constant touch with the people.” Nehru is reported to have consoled the general that as a sportsman himself he represented India to a sporting nation. But the real intention, clearly, was to get him safely away.

Dalliance with Politics

By the time he came back from Australia, Cariappa was a forgotten man. Nehru’s forebodings about the General were confirmed by the naive statements the General made from time to time. In 1958, for instance, he visited Pakistan, where army officers who had served with him in undivided India had just affected a coup. Cariappa publicly praised them, saying that it was “the chaotic internal situation which forced these two patriotic Generals to plan together to impose Martial Law in the country to save their homeland from utter ruination”.

Cariappa wasn’t the type to be content to live a quiet life even when he was getting old. In late 1960’s, for instance, he sent an article to the Indian Express, in which he argued that the chaotic internal situation in West Bengal demanded that President’s Rule be imposed for a minimum of five years. Personally, I think the old man wasn’t too wrong. However the recommendation was in complete violation of both the letter and the spirit of the Constitution. The newspaper’s editor was wise enough to return the article pointing out to the General that “it would be embarrassing in the circumstances both to you and to us to publish this article”.

On the whole, the pattern set in those early years has persisted into the present. As Lieutenant General J. S. Aurora said, Nehru “laid down some very good norms”, which ensured that “politics in the army has been almost absent”. “The army is not a political animal in any terms”, and the officers “must be the most apolitical people on earth!”. It is a striking fact of our political history that no army commander has ever fought an election. Aurora himself became a national hero after overseeing the liberation of Bangladesh, but neither he nor other officers sought to convert glory won on the battlefield into political advantage. If they have taken public office after retirement, it has been at the invitation of the Government. Some, like Cariappa, have been sent as ambassadors overseas; others occupied state governorships. For years now the retiring Chief of Army Staff almost unfailingly gets appointed as Governor of Arunachal Pradesh.

However, over the years the story has been in circulation that Jawaharlal Nehru had a lurking fear in the 1950s that General K M Cariappa would engineer a coup against him? A recent biography of Cariappa, authored by his airman son Air Marshal K C Cariappa says that because of such an unfounded fear, his father was packed off to Australia as India's High Commissioner – out of sight, out of mind – in 1953! Though the first C-in-C of the Indian Army had a cordial relationship with Nehru and Indira, there was an “undercurrent” of suspicion.

However, over the years the story has been in circulation that Jawaharlal Nehru had a lurking fear in the 1950s that General K M Cariappa would engineer a coup against him? A recent biography of Cariappa, authored by his airman son Air Marshal K C Cariappa says that because of such an unfounded fear, his father was packed off to Australia as India's High Commissioner – out of sight, out of mind – in 1953! Though the first C-in-C of the Indian Army had a cordial relationship with Nehru and Indira, there was an “undercurrent” of suspicion.

“Father was perceived as being too popular, not only in the Army but among those in other walks of life too. Perhaps, there was a lurking suspicion that he might engineer a coup. Nothing could be further from truth.”

The author recalls that his father was asked on many occasions why the Army did not evict the frontier tribesmen who had attacked India supported by the Pakistani Army and why it was decided to have the ceasefire line dividing the State. The General used to reiterate that it was the Government who dictated policy. At the time, the Army had its ‘tail up’ and was confident of clearing most of Kashmir and taking back Gilgit. But orders were received to “cease fire midnight 31st December/1st January 1948-1949.” The General said that the Army was very disappointed, but orders were orders.

A few years later, General Cariappa is on record, his son chronicles, to have asked Nehru the reason of the ceasefire. “You see the UN Security Council felt that if we go any further it may precipitate a war. So, in response to their request we agreed to a ceasefire,” Nehru said, adding: “Quite frankly, looking back, I think we should have given you ten or fifteen days more. Things would have been different then.”

Both Gen Cariappa and later Gen KS Thimmayya, the biography brings out, warned against the threat from China. But Nehru was too much under the spell of his Defence Minister Krishna Menon to see the looming danger.

The book notes that in 1951, there were disquieting events in the North-Eastern region when Chinese troops were caught with maps showing some parts of North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) as part of China. Because the Army had no operational responsibility there, the region being under the Assam Rifles who were under the control of the Governor of Assam, General Cariappa asked Nehru for directions in regard to the responsibility of its defence. The General considered it his duty to caution the political leadership of the possibility of an attack in the region. He was ridiculed by Nehru with “it is not for the Army to decide who the nation’s likely enemies would be!”

Contribution

How great a military commander K M Cariappa was is moot issue. However, he did play a crucial role in the transformation of Indian Army into a stable and stabilizing institution of the polity. Indeed like many Indian officers of that generation, Cariappa was perhaps more British than the British themselves. He relished to be called by his nickname “Kipper”. Almost all Army commanders – and I had the privilege to know some of them – had English nicknames. Sam Bahadur and Charlie Murthy are not just stray examples. One of Caariappa’s first acts as army chief was to establish an Indian regiment of Guards. Obviously he had the British model in mind to perform ceremonial duties.

Cariappa, however, had the right instincts and adroitness to adjust to the new order he was called upon to lead. He was sharply aware that India’s military needed to reassure national leadership by being sturdily apolitical. He realized that the armed forces must reinvent themselves. So, he successfully persuaded Nehru not to readmit into the Army the officers and men who had defected to the I.N.A., which grossly violated much-prized traditions of discipline. He wasn’t the one to compromise military discipline at any cost. As army chief, Cariappa repeatedly emphasized the paramount need for the Army to remain aloof from any kind of partisanship.

“Understand politics, but do not get involved in its processes”, he told his officers in 1949. “I want to make it clear”, he informed the ranks, “that you are not politicians... You are Indians first and Indians last”. At another level, Cariappa worked at Indianizing the army and raising it in the politicians’ and public’s estimation. Whereas high ranking British officers remained in important positions in Pakistan’s armed forces way into the 1950s, the majority of Britons seeking to hang on in the Indian army were transferred out within a year of Independence. “The Indian army in independent India”, Cariappa declared in his first speech to the press as Army Chief in 1949: “was a people’s army and the gulf that previously existed between the army and the people was now a thing of the past”.

Isn’t a skillful work of nationalist re-imagining that despite all this indigenization the officers’ messes of the more traditional Indian regiments still display on their walls, paintings by British military artists of Indian troops fighting for Queen Victoria’s empire or prints of fearsome Indian soldiers in the ornate uniforms of the Raj? Such displays do not convey imperial nostalgia but are, nonetheless, a remnant of our inseparable British connection.

Continued to The Man Who Exorcised the Specter of Coups

26-Apr-2013

More by : H.N. Bali

|

>Such displays do not convey imperial nostalgia but are, nonetheless, a remnant inseparable British connection.< No ‘imperial nostalgia’, yet the ‘inseparable British connection’ is clearly a prevailing awe of British excellence of form finds continuity in all things Indian, in government and the armed forces, and in everyday life, in the modernisation Empire brought to India. It is as though the British Empire has outlived itself in the excellence manifested in the British image and likeness, colonies now self-governing would appropriate as their own, even something as basic as a national flag and anthem. This is generally the course of civilisation where Empire has been the means of spreading an ideal of one government over a diversity of peoples; a unifying influence that has always been viewed by the imperial power as providential, but that has always proved to be self-defeating in the persistence of a people to identify with a country to relieve them of what turns out to be the imperial yoke; but once shaking off the imperial yoke to appropriate the tried and tested imperial forms of government and military organisation as its own. Perhaps, herein lie the roots of corruption in these quasi-imperial regimes of national government – that everything is posed as for the good of all but directed to the interests of the few. |

|

.Your statement,"...The General considered it his duty to caution the political leadership of the possibility of an attack in the region. He was ridiculed by Nehru with “it is not for the Army to decide who the nation’s likely enemies would be..." was absolutely true. I have read that in one of the leading news papers of India as reported by a bold writer sometimes in 50's if I recall. He had advised Nehru to take action to throw out the Chinese out from Ladakh ASAP. Often, I wish if only Nehru - my immense respect and admiration for him withstanding- , had taken the advise of FM Kariappa before the Chinese occupied Tibet and then giving brave but Ill prepared and equipped Indian Army such a humiliating experience. One more recollection about FM Kariappa is as follows. We had invited him to our Engineering college in (Chromepet) Madras in 1957. He arrived on time unattended in the train and then walked all the way to the institute to deliver the lecture. It was a remarkable act of modesty for all to remember. Prabhu, Canada Thank you mr. Bali for writing and keeping memorable events alive for the current and future generations of India and writing a beautiful article too. |