Apr 18, 2024

Apr 18, 2024

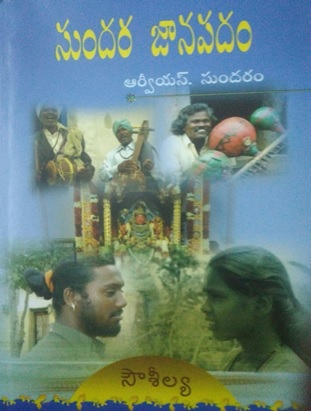

Sundara Jaanapadam, Prof R V S Sundaram,

Sausheelya, Keerthana Graphics, Mysore, April 2017,

pages 310 Paper Back, Price Rs. 200/-

Prof RVS Sundaram is a renowned academic who served in the universities of the South, Telugu Viswavidyalayam and Mysore University. For this book Prof SaLva Krishnamurty of Presidency College , Madras wrote in 1976 a brief note of good wishes and blessings called traditionally mangalaashasanam to Prof Sundaram for the first edition of this book. It was written by Prof Salva that folk literature is basically produced by many. The fruit of its study as per the societal view of acquisition of knowledge in several fields like anthropology, sociology and psychology. In many aspects of folklore writing polygenesis, propounded by Andrew Lang, is pertinent as also plausible.

Prof RVS Sundaram is a renowned academic who served in the universities of the South, Telugu Viswavidyalayam and Mysore University. For this book Prof SaLva Krishnamurty of Presidency College , Madras wrote in 1976 a brief note of good wishes and blessings called traditionally mangalaashasanam to Prof Sundaram for the first edition of this book. It was written by Prof Salva that folk literature is basically produced by many. The fruit of its study as per the societal view of acquisition of knowledge in several fields like anthropology, sociology and psychology. In many aspects of folklore writing polygenesis, propounded by Andrew Lang, is pertinent as also plausible.

The book under review contains two parts and as such is best reviewed in two parts. In this book, the first part contains introduction and five sections: folk poetry, narrative prose, poetic/lyrical narratives, adages and finally riddles. At the end are source book lists and a list of technical words. The introduction lists various areas of folk lore, folk knowledge and folk writing and living – all of which get conjoined in the term folkloristics. Folk are not merely villagers. Prof Sundaram quotes what Alan Dundes says: “The term folk can refer to any group of people what so ever who share at least one common factor. It does not matter what the linking factor is – it could be an occupation, language, or religion – but what is important is that a group formed for whatever reason will have some tradition which it calls its own.” (p.2) In this volume as noted earlier all the five sections are explained in that order so that they give adequate information about each very briefly to both Telugus and Kannadigas. Culturally in the south there are four languages, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam. Telugu and Kannada are closely related both linguistically and sociologically. Prof Sundaram writes about how all the five sections of compositions and their excellence in revealing how the people who express their joys and sorrows with flair and great concern. They have the talent of self-expression and as such they remain a treasure trove of traditional life and living. In the first section, folk lyrics, songs and poems are dealt with.

Narrative poems are in the second section. One of the important facets of these is that their authorship is not established or remembered. They become just public property. And they shine with their impersonality. These can be divided in several ways. One readily plausible is the division being inter-traditional. The author mentions C.P. Brown’s interest in their composition by making a Jangama, itinerary or mendicant singer at his place and listen to narratives like Bobbili Katha, Kamara Ramudu tales. These played an important in sustaining public interest in this kind of narratives.

Prose narratives are in the third section. These are perfect tools to study and explore our ancient traditions and culture in distant parts of our country. Talking about these it is important and useful to consider them in their motifs and types. Prof Sundaram praises the efforts of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson with which their book The Types of the Folk-Tale came out in 1928. Folk tales do not begin with a prominent action or conclude suddenly. As the two German brothers Jacob Grim and Wilhelm Grim view, Prof Sundaram propounds an Indo-European theory about folk prose narratives. In that motif index and type index are playing a great part in the study of Janapada, folk stories. Puranas are narrative tales including extra-human devatas, celestials and demons. The author says that as in linguistics, these narratives also must be elaborated at three levels, descriptive, comparative and historical.

Adages and proverbs are listed in the fourth section. We are told that Roger D. Abrahams defined these which we call saamethalu in Telugu thus: “Proverbs are short and witty traditional expressions that arise as part of everyday discourse as well as in the more highly structured situations of education in judicial proceedings.” (p.45) Brevity is one of the essential features of these. We say pilliki chelagatam, elakki prana sankatam meaning ‘for the cat a funny game, for the rat imminent death’. Born as either narrative, descriptive of sociological utterances to express joy or grief, they convey feelings with subtlety, aptness and quickness. These are often used with a flair for retort. R.S.Bags , as quoted by Kenneth and Mary Clarke in Introducing Folklore, suggested a numbering technique from 1 to 7 to assess their variety. Bags differentiated 1. Proverbial Metaphor, (A new broom sweeps clean) 2. Proverbial apothegm, Maxim, generalizing (Seeing is believing) 3. Blason populaire, used about men or places (It takes nine tailors to make a man) 4. Wellerism is funnily illustrative (Every man to his taste said the farmer when he kissed his cow) 5. Proverbial phrase, like an adage, (To break the ice) 6. Proverbial comparison (As white as snow; wiser than Solomon.)

The fifth division is Riddles or stories, which could be ballads expressed in verse. These are primarily witty.

This book stands testimony to the writer’s extensive scholarship, particularly on folk lore related literature, wide experience, observation and research with deep analysis of folkloristic studies both in Andhra and Karnataka. The extensive list of Western writers since 1946 makes the readers enthusiastic to go into them for further understanding.

~*~

Doctoral dissertations may not be usually read by general readers. People joke (unceremoniously) that dissertations are not read by others except the examiner(s). But this book coming from Prof Sundaram is unique. Scholars and general readers fond of folkloristics read this book with interest for the subject, which has gained currency in the last few decades. It was in 1973 that the scholar Sundaram’s got recognition for his study of folkloristics. The work was on ever day spoken language called vyavahaarika bhasha, language used in daily discourse, by the general public. The thesis was printed in 1979and since then its circulation increased owing to its being a comparative study of the two south Indian languages Kannada and Telugu.

The second part of the book now under review starts with this geyam, a lyric, a popular song with rhythm, beating time as in music, as a dedication. Here is a rough and ready rendering of that:

When the hamlet sings there is rhythm

When the sea rises and spreads there is rhythm

When the koil of the heart raises it voice there is rhythm

When the full moon shines all over there is rhythm

When the flower born the day before laughs there is rhythm

When yesterday’s flower drops down there is rhythm

In the pace of Time Man there is rhythm

When thoughts sweet remain in my still heart- mind

Dedicated to this flower are all those.

-Sundaram

The researcher travelling in Nellore and Chittur in Andhra Pradesh and Kolar in Karnataka gathered five hundred folk songs and studied their content besides their sensitivity and wonderful perception. Folk songs express multitudinous feelings with delectable precision and subtlety. Folk songs and folkloristics have attracted the attention of not only our poets and scholars but also those in the Western countries. Among the Telugus Nedunuri Gangadharam and Sripada Goplakrishna Murty, and among Kannadigas Dr S.GaddageemaTha and Dr, Shivaram Karanth are just a couple of names cited from each state.

Telugu an Kannada are closely related and in a sense, they are cognate. Folk lyrics are an integral part of popular culture and ours is a country with splendid cultural variety. In our two languages, both in numbers and emotional variety, the most prominent are geyas. These electrify, relieve, pacify, cajole, and evoke very sensitive feelings. There are innumerable kinds conveying different feelings and sensitivities of both men and women. In the agricultural land in different contexts different kinds of songs are sung by both men and women. Love, beliefs, joy, and all kinds of feelings are roused and thy alleviate hardship in work. In different occupations, in different locations, different songs are sung. There may be any number of changes in the lyrics in places of work for relaxation. Women have their own songs while pounding grain in with pestles or turning the stone-wheels for grinding. There are subtle differences in the songs of women from different social strata. In metaphysical or philosophical ideas and feelings there are three different types, some laudatory some enthusing or correcting attitudes in the lyrics. Among the Kannadigas many are Shaivites while among Telugus many are Vaishnavites.

Women’s songs are of various subjects. Singing the babes to sleep there are cradle songs and lullabies. There are lyrics for various occasions for various times, birthdays, weddings etc and for children, men and women expressing various kinds of feelings and emotions. During the year there are many festive occasions like Samkranti, Bhogi and worshipping many goddesses like Bathukamma, Boddemma. For some kind of cultural or family festivities lyrics and singing are extensively used.

Love lyrics are sung on occasions for merry making like consummating weddings where the bride and groom are sent into the bridal chamber. Women’s lyrics are their own and special. There are lyrics of in merriment between women pulling one another’s leg. There are questions and answers in them and arguments relating to faith and philosophy. When the bride is sent to her in-laws’ there are songs to be sung by muttaiduvas, auspicious married women. Among the innumerable familial relationships, the most important are mother-son/daughter, relationships among in-laws, mother-in-law, father-in-law, sons and daughters, etc. The lyrics most of the time stem from close relationships. After a lucid and extensive study of these geyas this illustrious scholar listed the fruits of research of many scholars at the end of the text. These would enthuse readers of this book to make their own efforts to contribute more to folkloristics. Classification and analysis of their respective significance would be the study of folkloristics. These foster societal cohesions by promoting mutual understanding and cultural unity.

Here is just one sample of a geyam in Telugu, a song of a widowed daughter-in-law

Wish I had been a manche*

Wish I had been a tree that would be felled

Wish I had been a leaf for a goat to pick and munch

Wish I had been a pod for a crow to eat

Wish I had been a fruit for birds to peck at

Wish I had been a golden utensil to fill the milk my dad is milking

Wish I had been a churner for my auspicious mother to make butter milk!

(* a shed created on poles commanding seat for the one who watches the field)

The author of this book quotes this as an expression of heart-rending grief of the young daughter-in-law.

This researcher suggests that the distinctive features of all lyrics need to be listed, analysed and the statistical analysis is made available for further improvement. Broadly speaking among folk lyrics, the qualities of Kannada and Telugu compositions go on varying from group to group, family to family and their locations. They are context-based, gender-based and family based. No musical instruments are used for those songs and they may be in groups facing one another. The conclusion of this researcher is that folk lyrics in Kannada and Telugu have intense similarities. Some features found in Kannada are not there in Telugu and regional variations persist.

There is an extensive glossary of nearly a hundred scholars and researchers on the subject in various languages with an addition of technical terms translated from Telugu into English.

23-Jul-2017

More by : Dr. Rama Rao Vadapalli V.B.