Apr 24, 2024

Apr 24, 2024

By the second century AD, the great Indian empires like those of Ashoka, and that of the Mauryans, had given way to a succession of regional dynasties in north India and in regions such as Bactria, Gandhara and as far afield as central Iran. Thanks to the preceding rulers, these regions were under the sway of a form of Buddhism that had evolved from that originally preached by the Buddha, to encompass an entire mythology consisting of Bodhisattvas and tales from the Buddha’s earlier lives. Buddhism had also evolved from a religion of monks and hermits to that of the state, and it was the state that patronized the large-scale production of images of the Buddha.

This transition from ‘aniconic’ to ‘iconic’ Buddhism is usually referred to as the later phase in Buddhist art and literature. The origins of the Buddha images are hotly debated. While western historians have traditionally held that Buddha images were a result of India’s interaction with Greece and its Hellenic cultures, Indian historians like Ananda Coomaraswamy (1926) have debated that Buddha figures can be directly traced to yaksha cults within India and are thus an indigenous production. Still another line of thought holds that the transition from the aniconic to the iconic phase corresponds to Buddhism’s development from the Hinayana philosophy to the Mahayana.

This transition from ‘aniconic’ to ‘iconic’ Buddhism is usually referred to as the later phase in Buddhist art and literature. The origins of the Buddha images are hotly debated. While western historians have traditionally held that Buddha images were a result of India’s interaction with Greece and its Hellenic cultures, Indian historians like Ananda Coomaraswamy (1926) have debated that Buddha figures can be directly traced to yaksha cults within India and are thus an indigenous production. Still another line of thought holds that the transition from the aniconic to the iconic phase corresponds to Buddhism’s development from the Hinayana philosophy to the Mahayana.

Kushan Art and Kanishka

Perhaps the earliest and most striking use of Buddha images comes from the court of Kanishka (78-101 AD) and the Kushan Empire. The Kushan Empire also saw the appearance of Mathura as a cultural and art center, producing a great many images of the Buddha. A key work here is the Buddha image by the monk Bala. Other images were not directly of the Buddha himself, but those of the Bodhisattva, with a number of striking details. Chief among these are features such as princely attire, jeweled accessories and elaborate hairstyles which mark the sculpture to be of royal lineage. That these statues have clearly Hellenic origins is shown from the style of the drapery and robes, very much like its Greek contemporary counterparts. It is also clear that certain modes of narrative and convention were followed, with Buddha figures often using mudras as marks of identity. While Kushan art is influenced by Greece, it also shows a fusion of Bactrian, Gandharan, Persian and Indian elements in its production.

Perhaps the earliest and most striking use of Buddha images comes from the court of Kanishka (78-101 AD) and the Kushan Empire. The Kushan Empire also saw the appearance of Mathura as a cultural and art center, producing a great many images of the Buddha. A key work here is the Buddha image by the monk Bala. Other images were not directly of the Buddha himself, but those of the Bodhisattva, with a number of striking details. Chief among these are features such as princely attire, jeweled accessories and elaborate hairstyles which mark the sculpture to be of royal lineage. That these statues have clearly Hellenic origins is shown from the style of the drapery and robes, very much like its Greek contemporary counterparts. It is also clear that certain modes of narrative and convention were followed, with Buddha figures often using mudras as marks of identity. While Kushan art is influenced by Greece, it also shows a fusion of Bactrian, Gandharan, Persian and Indian elements in its production.

Buddhist Art from the Gupta Court

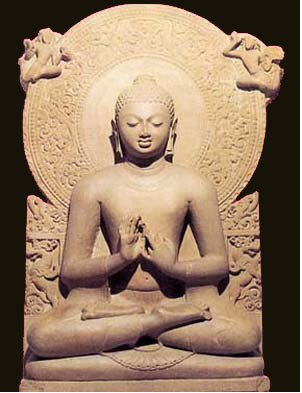

The Gupta court, generally regarded as the zenith of cultural achievement of ancient India, was also famous for its Buddhist art. Ambitious images of the Buddha, inspired by canonical texts on art by figures such as Yashodarman, show a fusion of the Gandhara and Mathura styles of art. Buddha images from this period are marked by oval faces, well defined eyes and noses, light transparent robes, as well as the delineation of the finger and hand mudras. Mostly commissioned by Buddhist monks, these images were perhaps the height of sculptural achievement for Buddha images during this period. It was after the Guptas that Buddhism in India, for lack of state sponsorship, went on the wane.

The Gupta court, generally regarded as the zenith of cultural achievement of ancient India, was also famous for its Buddhist art. Ambitious images of the Buddha, inspired by canonical texts on art by figures such as Yashodarman, show a fusion of the Gandhara and Mathura styles of art. Buddha images from this period are marked by oval faces, well defined eyes and noses, light transparent robes, as well as the delineation of the finger and hand mudras. Mostly commissioned by Buddhist monks, these images were perhaps the height of sculptural achievement for Buddha images during this period. It was after the Guptas that Buddhism in India, for lack of state sponsorship, went on the wane.

Cave Paintings at Ajanta

Buddhist art in India was not only restricted to images and sculpture, but also, as at Ajanta, produced magnificent cave frescos, many of which are still being analyzed by scholars for their picturesque beauty and artistic achievement. That these paintings followed canonical and a literary style is evident from the treatises on painting that date from this period. At Ajanta, the Buddha’s life and scenes from the Jatakas are painted in vivid color, along with ancillary paintings such as shipwrecks (attesting to trade links), romantic stories and war scenes. The narrative style employed at Ajanta prefers to eschew continuous movement, concentrating instead on individual frescoes that tell stories in ‘frozen’ movement styles.

Japanese Art

The later centuries of Buddhism in Japan saw the production of Japanese art that was heavily influenced by Zen philosophy – an offshoot of Buddhism.

The later centuries of Buddhism in Japan saw the production of Japanese art that was heavily influenced by Zen philosophy – an offshoot of Buddhism.  The same effect was aimed at with the production of Japanese gardens, where nature is approximated on a micro scale.

The same effect was aimed at with the production of Japanese gardens, where nature is approximated on a micro scale.

23-Jul-2010

More by : Ashish Nangia