Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024

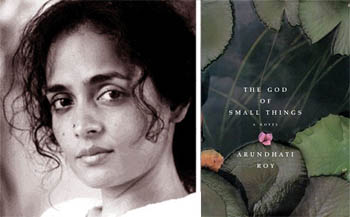

That Roy carves a fascinating story line isn’t so wondrous a reason for her writing — what’s most important is she sculpts an astonishing work from ordinary happenstance. She also emits a great sense of witticism — a potion of toxical hilarity. Her straight-line thinking works like sponge, absorbing pathos.

GOST celebrates bereavement, and just about every facet of life, in a way that is characteristically Marquezian. The novel also takes you on a transmigratory journey into the now, and beyond. In so doing, it emerges ever so sweetly — even heartbreakingly.

The novel is profound, and derisive, yes — sometimes, deliciously evil. It has tragic suffering, with more than an element of hope, and love, even if illicit — something that is quite ‘mesmeric’ to its ethos. Of final refuge — of life beyond human morality, inequities, or desires.

Roy is intensely mindful of her imagery, and allegorical resolutions, no less. She’s, therefore, wary with her choice of words — words which are delicately knitted to fit into every slot, angle, frame, and character. Her characters have a definitive sense of belonging, within each frame, word for word, too. And, they are all enmeshed within the gamut of their own feelings. They, sort of, belong — and, yet, they don’t belong.

They have their idiosyncrasies, no less: Ammu, with her own psychical traumas, Raphel and Estha, with their emotional twists, Chacko with his colonial hangover, and Velutha, with his low-caste label, or angst that goes with it.

What’s remarkably perceptive is Roy’s riveting mosaic vis-à-vis the unipolar tensions within the Syrian Christian community, juxtaposed by the radical Naxalite movement. Her surgical foray is more than exploratory. There is a definitive political underpinning, a multifaceted undercurrent flowing through her roller-coaster narrative, with Nature’s bounty — a veritable part of coastal India’s iridescent environ. This provides the novel a natural umbrella of sensuousness and refinement. A ‘feast’ of ephemeral ‘titillation’ — so to speak.

GOST evolves over just one day, and encompasses a few decades, back and forth. It X-rays how the little world of Ammu’s twins — Estha and Rahel — crumbles with the drowning of their cousin, Sophie Mol. It wades through the process of shock, human tragedy, disappointment, frustration, depression, and acceptance. It also illustrates dexterously how wreckages in family life distort perceptions and lead to making forecasts out of heretical beliefs.

This isn’t all. Roy brings out the high-handed, fragmented ways of the powers-that-be with Skinnerian panache, supplanted by a wacky sense of humour — even in the most serious, heartrending of situations. To cull one example: when Velutha, who’s falsely implicated in the tragic death of Mol, exists as a truncated vegetable — his life hanging on the edge of a whisper, followed by final silence — after the police ‘thrash’ him up. Even so, Roy gets her ‘punch-line’ right — a sombre political message that cannot be missed.

GOST has a delicate balance: a workable co-ordination of the mind-body process, brain, or insight. Not surprisingly, death, more than anything else, becomes a wobbling, terrestrial phrase in Roy’s raison d'être. It has shades of Schopenhauer: “Everything lingers for but a moment, and hastens on to death.” Of nirvana, where all individuals achieve peace — of wilfulness and salvation.

GOST smells of pickles, squashes, jams, and recipes, that could arouse your taste buds. It has rhapsodies reminiscent of The Sound of Music. At the same time, it has a morbid sense of unwanted ‘fun:’ of devastating homosexual fixations Estha is subject to, in the cinema hall foyer, for one. It also, perforce, goes without saying that Roy’s ‘harangue,’ at times, is an allusion to popular culture.

Nevertheless, GOST, in all its essence, has passion, precision, and an ancient reciprocity with the natural world — the breathing world, of sustaining relationship with life, human cognition, triumph, fallibility and, most importantly, intellectual intrepidity.

A novel that changed the landscape of Indian writing in English like never before, GOST is a fascinating, uncoiled lacework of human revelation and (un)certainty. Ten years on, it continues to be a marvelous work — a delicious nectar in print.

10-Jun-2007

More by : Rajgopal Nidamboor