Nov 04, 2025

Nov 04, 2025

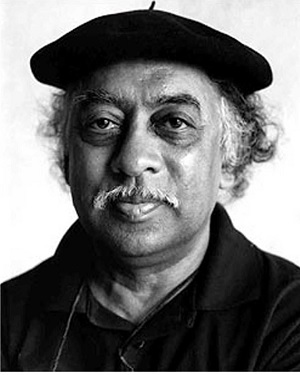

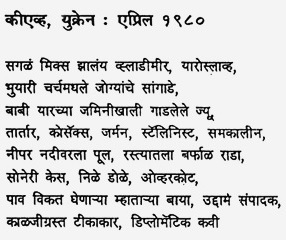

Kiev, Ukraine: April 1980, which has been translated from Marathi, is a superb poem dealing with Ukraine, topography and cartography of it, depicted through the cultural spaces, as marked by the poet Dilip Chitre, who was on a visit to the land, forming a part of the Soviet Union then and thereafter, registering his impressions and feelings, in the form of poetry let out, as the experiences formed by an outsider, which none the else but he could do it so, as for being adept in, translating from Marathi into English. The poem is celebratory of that tour.

Kiev, Ukraine: April 1980, which has been translated from Marathi, is a superb poem dealing with Ukraine, topography and cartography of it, depicted through the cultural spaces, as marked by the poet Dilip Chitre, who was on a visit to the land, forming a part of the Soviet Union then and thereafter, registering his impressions and feelings, in the form of poetry let out, as the experiences formed by an outsider, which none the else but he could do it so, as for being adept in, translating from Marathi into English. The poem is celebratory of that tour.

The poet visited Ukraine as a visiting writer of the delegation when en route to Europe journey. An editor, a visiting fellow, a traveller, what was he not? To arrange for poetry festivals, symposia and seminars was a part of his academic activity. Taking stock of the composite Soviet Union under which the land had been, feeling the pulse of man, he marks the geography, art and culture of the people, the historicity and religious allegiance of the populace. How the courses of history? What was it in the past? How the history and culture of it? How the belief of the people? Ukraine as a republic, how would it be? How had it been under the Soviet Union? How the domain and the territory? The history of Ukraine, how to know it? How will a visitor assess it? How a foreign tourist? How the legacy and heritage of it? The discussion about Ukraine reminds us of Lawrence’s visit of Mexico, Sardinia, Sicily and others. There is something of the travel material in it.

One may not understand the poem if one knows not the history of Ukraine, the history of the lands other than Western Europe. How to explain the meaning and significance of the word Yaroslav? How to explain it Vladimir? The names have several connotations and references. The historic churches and archives, caves and the places containing the skeletons of the monks tell of the land and its history, the faith which it upheld them, upkept them. The space dotted with the Tartars, the Cossacks, the Germans, the Stalinists and contemporaries tell of the scenario with reference to political and cultural contexts cutting the ice of each other, breaking the silence. The bridge on the Dnieper river reminds us of Wordsworth on London bridge. The Dnieper with the course of its own traverses strange lands and domains and pictures it before scenery of the towns and cities upon its banks. Golden hair tells of the blondes and beauties in the costumes and cosmetics, dressing and design of their own. Here the girls with the white hair, brown hair, golden hair and curly hair dance over the mind’s eye. The matter though aesthetic is so much regional and global too. Why are the eyes blue? This too has scientific explanation. How had it been the local folks’ reactions? What do the Western people think about the blue eyes? Are they ismic about it or not? What to say it? How to take to it? Today many mod girls like to brown their hair. Hardy’s A Pair of Blue Eyes too can be referred to in this context. The girl with the black hair the poet does not discuss it here. While reading the poem, the girl with the cat’s eye and the public’s reactions in our country too does the rounds. The line is beautiful, so lovely in expression, “Golden hair, blue eyes, the overcoat, / Old women buying bread, the arrogant editor, / The worried critic, the diplomatic poet.”

The old women buying bread represents our livelihood, the day-to-day affairs of our life, how bread and butter is important for a living. The bare realities, the ground realities can never be sidetracked. The arrogant editor may refer to the strict press. How do our liberties remain toned down during a communist regime? How is it censured the freedom of press? How is freedom restricted? How does the freedom of speech and expression remain it restricted? The communist press and the papers with their chosen editors and public correspondents may censor it all as a tool of the government. The worried critic may refer to the critic of communism as they dare not criticize fearing a backlash. The Tartars, who are they? What they to Ukraine? This too has perhaps a history. The Cossacks too adds meaning to the poem under our perusal. The Stalinists too cannot go unread as it too has a meaning. How did the Stalinists take to? How was their concept of communism? How the communist federation was lengthened? How their concept of revolution and rebellion? How did they oust Trotsky? How the contemporaries? The diplomatic poet reins in the picture of a democrat poet under a communist regime handling poetry diplomatically. To see it otherwise, a diplomat too can be a poet. Together with it, the image of a political poet can also be not denied. Does the poet not do politics? Do they not self-publish? Is poetry not propaganda? While discussing it, the pictures of Mayakovsky, Brodsky, Neruda, Seferies and others come before the eyes. When we read the poem, we think of the spies and their treatment during the Cold War. The ice and slush shows the difficulty faced during the snowfall and ice covering it up. At that time mud and slush put in hurdles to steer across. The talk of the Tartars takes us to the Crimean space and their settlements and the treatment meted out to them during the Stalinist regime apart from whatever be their history. Several things inter-cross us while reading the poem for a review and critique. During the winter time, frozen water and falling snow take us aback with its landscape and scenery.

The image of the old woman buying bread brings us to the ground. The poet as a visitor marks it all, tries to know the history of it cutting the cultural ice. It is a poem of Ukraine and his visit.

History of Poland, history of Hungary, history of Belarus, how to write it? How to know it as none taught us and we remained engaged in England, Portugal, Spain, France, Russia, Germany and America. There is also an alternative history. History of Ukraine, how to go through the ups and downs of it? Again to talk of Ukraine is to talk of Armenia and Azerbaijan and to talk of Crimea is to discuss Nagorno-Karabakh.

When we talk of the Stalinists, the ghosts of Trotsky haunt just like Hamlet on being haunted. When we talk of the Stalinists, the Marxists and the Leninists, the Maoists come down to us as a trail of imagery.

The Germans, how did they mesmerize history? What treatment did they mete out to the Jews? What to say it about? England, Portugal, France and others, they too had nothing but to find new colonies on their minds. What to say it about Turkey’s history so fraught with the victory of the sword? What to say about the nomadic peoples and races? Savage and barbarian people?

The poem is a history of the town and reading it, we feel it within to know the histories of other towns in the likely manner. The scenery of Kiev on the banks of the Dnieper he sees them at a glance, the landscape so lovely with the green cover of its own.

The word ‘Stalinists’ brings it before the image of the competition, the propaganda war in between the USSR and the USA as the broadcasts of the Voice of America and Moscow Radio used to do it then. How had it been the days of Pravda? But Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Yeltsin and Gorbachev toned it down town after another the harsher voice of blatant, belligerent communism.

It’s all mixed up: Vladimir, Yaroslav,

It’s all mixed up: Vladimir, Yaroslav,

The skeletons of monks in the underground church,

The Tartars, the Cossacks, the Germans,

the Stalinists, the contemporaries,

The bridge on the Dnieper River,

the ice and slush in the street,

Golden hair, blue eyes, the overcoat,

Old women buying bread, the arrogant editor,

The worried critic, the diplomatic poet.

05-Feb-2022

More by : Bijay Kant Dubey