Aug 19, 2025

Aug 19, 2025

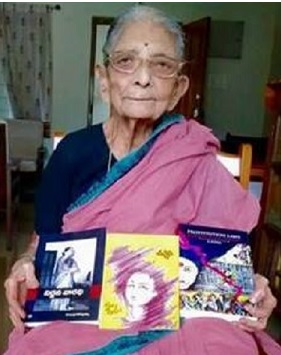

Nirjana Varadhi (2012) is an autobiography of Koteswaramma that runs against the backdrop of the communist party movement in coastal Andhra of the 1940s and 50s. It reveals how dispossessed and marginalized she was and yet how empowered and ready to accept the challenges and wither them away with passion, compassion and grace. Time and again, Koteswaramma, as a woman, a communist party activist, a deserted wife, and a bereaved mother waged a relentless battle with the firmest fortitude against the status quo in a stormy terrain of -isms and gender prejudices. Her undertaking the narration at the ripe age of 92 subtly shows how determined she was to ‘speak out’ for the marginalized. This paper shall now attempt to trace the ‘multiple selves’ of Koteswaramma from her ‘unmediated voice’ as echoed in Nirjana Varadhi coherently with purpose and significance.

Autobiographies in Telugu, a product of the influence of English literature, hardly count to a little over a hundred. Among them, only a few merit our attention (Datta, 1994), while autobiographies of women are often relegated to oblivion. This scenario has however changed with the publication of Nirjana Varadhi (2012)—Abandoned-Bridge—an autobiography by Kondapalli Koteswaramma, widow of Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, founder of the People’s War Group. It is a remarkable piece of work, to say the least. Narrating her endless ordeals, the biography also functions as a sociography, particularly throwing light on the communist party movement in coastal Andhra during the 1940s and 50s.

Autobiographies in Telugu, a product of the influence of English literature, hardly count to a little over a hundred. Among them, only a few merit our attention (Datta, 1994), while autobiographies of women are often relegated to oblivion. This scenario has however changed with the publication of Nirjana Varadhi (2012)—Abandoned-Bridge—an autobiography by Kondapalli Koteswaramma, widow of Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, founder of the People’s War Group. It is a remarkable piece of work, to say the least. Narrating her endless ordeals, the biography also functions as a sociography, particularly throwing light on the communist party movement in coastal Andhra during the 1940s and 50s.

Unlike a man’s autobiography, her narration of self is dotted with such revelations which, to borrow Stanton’s (1987) words, “essentialize women’s life experience.” Intriguingly, it is the communist party and its revolutionary movement that forms the backdrop of the narration about her “innermost gendered feelings.” Her story covers three generations of a communist revolutionary family that worked for the emancipation of marginalized and oppressed sections of society. It narrates the unexpected turns that Koteswaramma’s life took at various points in time and how those twists were negotiated by her, that too, without depending on anybody else, to move forward, and that is what constitutes the core of this autobiography.

In this autogynographical narration, we witness a visible tension between the conventional role of Koteswaramma as daughter, wife, mother, and another—the unconventional ‘self’ that had communist party’s ideological longings. In her long journey of more than eight decades through the stormy terrain of isms, movements and gender prejudices and the resulting ‘tension’ from those ‘conflicts’, we encounter ‘multiple selves’ of Koteswaramma that illuminates her personality as an ideal of self-sacrifice, nay an epitome of the struggle between a woman and her fate. We could also clearly see that this narration is not just confined to Koteswaramma’s multiple selves but the “lifelines” of her “‘I’ that came from and extended to others” too.

She penned this journey in an almost story-like narration of ‘self-making’— beginning with her childhood and progressing through various stages in life and ultimately ending with her moving out of the old-age home to her great-grandchild’s home as her age was no longer permitting her to carry on all alone. To a certain extent, this biography could also be seen as a political text of the Marxist movement in coastal Andhra of the 1950s—indeed throws light on the first generation of communists/revolutionaries in the making. Addressing her narration to the society at large, she says that she would feel happy if the reader perceives her book as though meant for refashioning the society, and if it anyway aids the growth of ‘goodness’ among people even a wee-bit. The very fact that she wrote this book at the ripe age of 92 is a testimony to her ambition.

We shall now take a critical look at some of the important events from her ‘self-narrative’ that not only showcases her multiple selves but also reveals how she managed to journey through the ‘tension’ created by the conflicting demands from different selves and through these incidents, we shall evaluate to what extent the narrative encompasses Cavarero’s (2000) configuration of the narratable self in the ‘I/you/we’ network of relations and the honesty thereof. We shall also examine how far the narration serves as a sociography.

1. Koteswaramma’s Biography

In her narrative, Koteswaramma gives a candid account of her personal life as well as her role in the communist movement of coastal Andhra of the 1950s. She presents vibrant images of her reminiscences that are well correlated to the external events and her inner emotions and resulting experiences. At every stage in her life, she appears to have been guided by Marxist philosophy. An element of concern for the overall welfare of the fellow beings could also be discerned in her orientation toward life. And, all this is very evident from the different phases of her life listed hereunder:

1.1 A Child-Widow with a Fervour for India’s Freedom Struggle

Koteswaramma was born in 1918 in Pamarru village of Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh, in a middle-class family. She was married at the age of five and became a widow at the age of seven. She went to school and won the affection of teachers with her all-round performance. She was however not aware of her widowhood till a girl in the school mockingly said, of course, more out of jealousy: “seems her husband died, hence teachers are treating her caringly”. When she was 10 years old, Mahatma Gandhi came to their village. Watching the women of her village devotedly offering their jewellery to Gandhiji, Koteswaramma, inspired by the scene, removing whatever jewellery that she could easily pull out from her body, put them in Gandhiji’s palms. Hopping and singing “Vande Mataram” as she came home, her amma shouted at her: “Whether or not India gets independence… this girl got it… given away jewellery without asking elders and came home fearlessly.” Her father however praised her. While studying 8th standard, she, quitting the school, joined the independence movement, actively participated in the rallies and sang patriotic songs in the meetings.

1.2 Marriage with a Communist Party Worker

Her mother was anxious that she be remarried. But fearing for society, her father could not take the idea forward. However, at the initiative of Comrade Chandra Rajeswara Rao, and with the encouragement of the teachers’ union and other progressive elders of the village, Koteswaramma, at the age of 18, got married to Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, an active worker of the Communist Party. After being through the usual teething problems of widow marriage, she could finally settle in her in-law’s house. Seetharamaiah, a devote follower of the Communist party dictates, sold his share of the property and gave the sale proceeds to the party. His mother was not happy about it. She was also not happy of Koteswaramma participating in party activities. Blaming, “It is on marrying you that my son became like this”, she used to curse Koteswaramma. To avoid these daily squabbles the party directed Seetharamaiah to shift himself with his wife to a nearby village. There she gave birth to a male child but he died within a few months, perhaps, “sensing that his mother doesn’t know how to nurse him”. In the meanwhile, as the government banned the communist party, Seetharamaiah went underground. In 1942 she gave birth to a male child. Two of the party sympathizers introduced by Seetharamaiah before he went underground, visited her regularly, and unmindful of the police threat, attended to her needs.

1.3 As an Active Communist Party Worker

With the lifting of the ban on the communist party, all the comrades came out into public. As her husband was asked to stay in Vijayawada and take care of the party affairs, they shifted to Vijayawada. The party decided to involve women folk of party activists to strengthen it further. They educated them in party philosophy by conducting classes. Of her own volition, Koteswaramma began working as a party activist. Besides working with Mahila Sanghams, she, as an active member of the cultural troupe, took part in party rallies. Reproducing party literature, sold it in villages.

Koteswaramma gave birth to a female child in 1944. Comrades named her, Karuna. Accusing that the communist party is supporting the armed revolt of Telangana peasants that started in 1946, the government banned the party and its publications in Andhra. As women activists of the party took out a rally demanding for lifting the ban, they were arrested and sent to jail. With continuous harassment from police, women activists felt highly insecure. Fearing police raids and imprisonments, even parents of party activists refused to allow them into their houses.

1.4 A Revolutionary Leading a Dreadful Underground Life

As the repression of active Communist party workers’ movement became severe, Koteswaramma was forced to go underground along with others for five years leaving her two young children behind in the care of her mother. She, moving from one safe den to another, spent five frightful years in seven towns—Bandaru, Eluru, Visakhapatnam, Poori, Nagpur, Rayapur and Gondia—under different identities. While in the underground, she used to cook food and feed the underground comrades besides copying the secret documents of the party for distribution.

1.4.1 Her brush with death

As a pregnant woman, being unable to undertake hard work, she worried that she might become a burden to the den. Perhaps, feeling the same, comrades suggested abortion. And being scared of taking her out to a hospital as that might pose a threat to the other underground leaders, they resorted to some crude practice. That caused profuse bleeding. Yet, they were not in a position to let any outsider know of her condition, for it may endanger the lives of other comrades in the den. She could not even hang the washed blood-stained clothes on the washing line. Owing to non-stop bleeding, Koteswaramma’s position deteriorated so badly that she could not even walk up to the bathroom which was located at a distance from the bedroom. In that trying period, a comrade attended to all her needs. As the bleeding continued, they finally managed to get a doctor, of course, in disguise into the den. On examining her condition, the doctor, declaring that had her visit been delayed by another hour, Koteswaramma might have died, warned the comrades not to resort to such crude practices henceforth.

1.4.2 Scary, grim and outrageous anecdotes from dens are not uncommon

Then she was shifted to a den in another town. There she heard about male inmates of a den asking women folk, in the absence of its manager, to fulfil their carnal urges. Despising them, the ladies could manage to bolt them inside the room and stayed outside for the arrival of the den-keeper. Learning about this incident, a lady comrade questioned Chandra Rajeswara Rao, party leader thus: “Without fearing the police and being fully aware of the consequences, but for faith in Party that we ladies came to serve the party. We are feeding the comrades like mothers. Is it for suffering such heinous crimes that we came? No difference between a communist and a lecherous fellow? Henceforth, you should keep all married women along with their husbands in the same den.” Discussing it threadbare, the party came to the conclusion that it is not always possible to keep wife and husband in the same den, as they are engaged differently in party activities. Citing the example of Koteswaramma’s husband, who is training the peasants of Telangana armed rebellion, he questioned, “Is it possible for her to be there?” He thus tried to pacify them.

1.4.3 Women-activists’ craving for children

Koteswaramma and Savitramma used to worry occasionally about the children they had left in the care of grandparents back home. Immediately, remembering the fate of those who are not having even grandparents to take

care of, felt comforting. They, retelling to themselves that revolutionary-women do not remember children, used to wipe out their tears. Yet their natural urge for caressing children cannot be suppressed totally. Believing that presence of the old people and children in a den make it less suspicious for the police, party housed a new lady with a child in the Rayapur den. That became a pleasant gift for the women inmates: they used to caress the child one after the other, despite the ill-health of the child who was suffering from diarrhoea.

1.4.5 A hapless communist party activist-mother

Party leadership of those days was more concerned about the safety of the den than that of the children of the party workers. In its pursuit, they did not even hesitate to use children of party-workers as cover against police suspicion.

Thus, surprisingly, even Koteswaramma’s children—Karuna and Chandu— once joined her in a den. Seeing them she was overwhelmed by pleasure and pain at once. Children too were shocked to see their mother all of a sudden. Of

course, that was not to last long. But the irony is: when her daughter, fondly recalling Hanumantha Rao uncle, an inmate of the den, and his narration of stories and his playing with them, asked her, “Amma, let us not shift to another

house, let us stay here”, Koteswaramma, being a party activist living underground, could not even say a word in reply except to stare in blank at them. Nor did her children enjoy that freedom.

1.5 Transition from Underground to Normal Life

On return from underground to her native place (perhaps, in 1951, for that was the year in which the ban on the communist party was lifted; unfortunately, Koteswaramma hadn’t paid much attention to record the dates), walking through Vijayawada streets she felt quite disheartened, for the streets were no longer decked up with red flags. Listening to the atrocities of the Congress government against communist activists, particularly gunning down of the leaders like Chalasani Jagannadha Rao along with his son and son-in-law, Chintapalli Paaparao et al., she wept silently. Watching the party leaders of the underground coming on to the public dais in Vijayawada amidst the cheering public, of course, gave her relief.

Later, she actively participated in the 1952 election campaign on behalf of the communist party contestants in coastal Andhra, North Andhra and Rayalaseema. During this journey, she encountered some unpleasant experiences from even communist party sympathizers’ families such as high caste people treating party campaigners of other castes as untouchables, an exhibition of male dominance even among communist campaigners, and unpleasant comments from the folks on the streets, such as, “you women, deserting husbands, with a bag slung around the shoulder, roam in the streets like foreign women and distribute party literature,” etc.

Intriguingly, Koteswaramma’s narration is silent about the normal trials and tribulations that radical activists, particularly women activists, who had gone underground faces on re-joining the mainstream life, for common sense tells that it would be more horrendous in the case of women activists owing to their lifestyle and aspirations that are different from men. May be, she left it to the imagination of the readers.

1.6 A Deserted Wife

Those were the days of hectic discussions about communist party splitting into two.As it was becoming more a reality, Seetharamaiah, her husband, enquired with Koteswaramma if it would be alright to house a woman who served the party both during the underground days and thereafter as she is suffering from epilepsy with no one around to take care of her. She, as a party activist, gladly agreed to take care of the martyr’s wife. Thus, Seetharamaiah brought that woman and her two children to their house.

But party members had a different opinion: they commented that she was looking after that woman with greed for her money. Over it, Seetharamaiah started accusing Koteswaramma that she was not looking after her well. Both these comments hurt her badly. Finally, that lady left their home with her children. Perhaps, smelling something fishy of this move of Seetharamaiah, the party asked him to go and work in Rayalaseema, hoping perhaps, that would resolve the issue, but as he refused to obey the orders, the party expelled him.

Thereafter, one day when children were not in, Koteswaramma asked him, “You are not coming home. Staying with that woman. What should I tell our visitors? How should I run the family?” Staring at her in wonder, he enquired: “Did anyone advise you to ask like this? Or, are you questioning me on your own? That lady actively supported the party even after her husband’s death. She extended support to the revolutionary movement of the party. Without caring for her own health, that ideal woman campaigned for the party. That is why everyone respects her. That is why you are jealous of her. Because I am moving closely with her, you are suspecting me. You were once a widow. Yet, I married you and took you on to party platforms, making people appreciate you. Watching you moving intimately with everybody, I too can doubt you, right?”

As a response to these words, all that she wrote in the narrative was: “Those words hit me hard”. Intriguingly, this is followed by an expression, which is unlike that of a Marxist activist but more like that of an average woman. Simply recalling what he said at their marriage function: “The purity of your heart is reflecting beautifully in your innocent eyes. That gave me the confidence that I could accomplish the goal I have set for myself. That is why I have given off celibacy deciding to live happily looking into your eyes”, she wondered, if he was the same Seetharamaiah! She wanted to ask him further… but without giving her a chance he went out, uttering: “don’t feel like seeing your tearful-face”. Later one night he came with a truck, picked up whatever he wanted and loading them in the truck went away declaring, “you and Karuna [daughter] stay in this house, me and Chandu [son] shall go to some other place… this is party’s decision.”

Later Seetharamaiah, sending Chandu for education to Madras, shifted to Warangal with ‘that woman’. Koteswaramma, staying back in Vijayawada with her mother and daughter, struggled to eke out her life. Karuna passed 9th class. But continuing her schooling has posed a challenge to her. One day Seetharamaiah sent a man to bring Karuna to Warangal for spending her holidays with him. The ‘mother’ in her raised a question: “How to send the child to a house in which that woman who is prone to frequent fits is staying?” But encouraged by her mother, she sent her to Warangal. Later he wrote a letter informing her that Karuna will join a school in Warangal and will come to her in the holidays. Here again, as a typical housewife she laments thus: “In spite of there being Seetharamaiah, I am widowed. Despite having children, I could not rear them.”

1.7 As a Student at the Age of 35

Seeing her plight, the party decided to return the value of gold that she gave to the party when the party was banned. But Seetharamaiah wrote to her directing not to take the money, threatening that if she takes money, she has to take care of children’s education. Knowing his stubborn nature and fearing that he might as well do what he wrote, she, in the interest of her children’s education, declined to accept the party offer. Life has become a struggle for her. Even her own party members castigated her for staying alone, citing the examples of women who put up with all the abuses from husbands in the interest of children. With no bitterness towards all these people, she, refusing to be cowed down, joined the home for destitute women maintained by Andhra Mahila Sabha in Hyderabad with the blessings of P Sundarayya, a communist leader, and enrolled herself for Metric examination. She earned a little money by writing stories, plays and participating in AIR programmes. Even under that severe economic strain, she continued to send Rs. 10 per month to party as the levy. Finally, she passed the Matriculation examination.

1.8 To Attend or Not to Attend Daughter’s Marriage

A fellow medico of Karuna and a sympathizer of the communist party, proposed to Seetharamaiah to marry his daughter, Karuna. He suggested that he better ask for Karuna’s opinion. Karuna in turn suggested Ramesh to take the opinion of her mother too. But party elders like P Sundarayya suggested to differ it till she completes her MBBS course. However, Koteswaramma, hearing that even parents from Communist Party are looking for dowry, gave her consent for the proposal. But as Seetharamaiah did not send her invitation card, she, as a revolutionary woman stayed back, sending a gift packet through a comrade friend to both the bride and groom.

1.9 A New Beginning as Matron

Later with the best wishes of P Sundarayya, she joined the girl’s polytechnic at Kakinada as a hostel warden. She proved herself a good mentor for the young students. As these young girls swarmed around her with affection, her suppressed womanly feelings used to surface occasionally: “Though I gave birth to children, I, having gone underground, could not nurse them when they were young. Even when they have grown up, by virtue of my staying away from them, I could not taste the pleasure of motherhood. To taste that at least in words, let me now write stories as though narrating to Karuna and Chandu”. Thus, Kakinada made her a creative writer.

On becoming matron of girls’ hostel, she lent financial support to her children for education. In the holidays, she used to go to her children in Warangal with gifts. In 1964, Seetharamaiah wrote her a letter asking for the divorce. When she shared this with children, her daughter, hearing it, remained quiet (p77). The tenor of this statement gives a feeling to the reader that she was not comfortable with that silence of her daughter. Her son had however asked her not to accede to his request but to remain as Kondapalii Koteswaramma, which request, of course, she finally honoured.

1.10 A Mother in a Marxist-Revolutionary

Hearing that her son, Chandu, a student at REC Warangal, was actively involved in the Naxal-movement of 1964 in Srikakulam district of AP, the ‘mother’ in Koteswaramma prompted her to request Tarimala Nagireddy, one of the leaders of the movement to advise Chandu and see that he works for the movement while pursuing his education. With a sympathetic smile, he subtly declined her request, saying: “What shall I reply if your son asks me as to why I, quitting BHU, joined the movement? Why did my mother quit her studies carrying the tricolour flag during the independence movement?”

In the summer holidays, she went to Warangal. On learning that her son is staying with Satyamurthy, a communist party worker, she, questioning, “Are you staying here because you could not pay hostel fees?” attempted to give him the money that she brought with her. “Not only hostel, but I am also thinking of quitting even college too”, replied her son. She felt like asking him: “Are you quitting because your grandmother is no more there to support your educational pursuit?” But immediately realizing that those who cannot afford to support his education have no right to question, she remained silent.

Later learning that Chandu was arrested, she went to the jail in Hyderabad to see him. He looked at her as though questioning: “You also went to jail, why this fear?” Seeing him speaking smilingly to her, she felt that he had inherited all the courage of Seetharamaiah.

Thus, at every stage, she, knowing her limitations, attempted to relate with everybody else, including even with her children, quite on realistic terms—never transgressing her boundaries and always safeguarding her self-respect.

1.11 A Bereaved Mother in Search of Solace

One day Karnataka police came to her and showing clothes and chappals, enquired if they belong to her son. She could not say yes or no. They, saying about his death, took her signature on a few papers and left. She broke down. But the pity was that she could not even cry openly. As though advising her to go to that place where she could garner a little relief, the students went on strike as a result of which hostel was closed and she could go to her mother in Vijayawada. But on reaching her mother, she, realising that she is not believing what the police had said and instead, thinks that Chandu went underground, had to swallow her tears all alone, lest her mother may not be able to withstand the tragedy at that old age.

1.12 Necessities Make one’s Heart a Stone

Her daughter and son-in-law on becoming doctors worked for some time in Dandakaranya Project hospital near Raipur and later shifted to Delhi. Their house became a centre for cultural activities of Telugu people in Delhi. Besides dispensing medical services, Ramesh, her son-in-law, got actively involved in many social projects. In connection with one such project one summer, before leaving for Yemen, Ramesh came to Vijayawada. He went around friends and relatives and literati in that blazing sun to collect literature pertaining to Gidugu Ramamurthy and died of heatstroke. In no time her daughter’s life turned topsy-turvy. Koteswaramma was lost in an impasse: “Whether to cry for the dead son-in-law or to console her crying daughter and granddaughters?” Stared at the pathetic scene thunder-struck. Friends stepped in and consoled Karuna and her children.

Later, in 1980 Karuna went to Yemen leaving the children behind. Koteswaramma wanted to quit the job and take care of children but a well-wisher advised her to go to Kakinada and join the job for it is essential for her survival as also for ensuring pension. Accordingly, Koteswaramma, “went to Kakinada in the company of her hardened heart.”

1.13 All Women Staying Under One Roof

Karuna could not continue for long in Yemen. She became pale and weak. Seeing her photo, Koteswaramma wondered, if the love of children is more necessary than even the importance of earning money for them. As she wished, Karuna returned home from Yemen within a year and a half.

Returning to India, she stayed in Vijayawada with her grandmother and children. In 1983, Koteswaramma, retiring from the job, returned to her mother in Vijayawada. Here she made a comment, which sounds typical of an ordinary woman battered in life: “me, my mother, Karuna and her two daughters—all women stayed together with no male companion.”

Here, she narrates an incident that makes a reader wonder if Karuna is indifferent to her mother’s wishes: When school management, believing that Koteswaramma would be an ideal person to manage their hostel meant for students, invited her, she did not evince interest in the proposal, for she thought she would be more useful at home to take care of the guests visiting the house and also take care of the children when Karuna is in hospital. But Karuna, thinking that the cook can take care of the home as well, desired that her mother should work voluntarily for it would be

honourable for the family. Inferring from it that Karuna wants her to go to hostel and hoping that she would be of some use to at least to the future citizens of India if not to those who had been born of her, she gladly went to the hostel. Here and there in the narrative, we come across such incidents where Koteswaramma felt ill at ease with her daughter’s responses to her wishes. Indeed, for the first time, she voiced her anguish at her daughters’ behaviour explicitly by quoting an axiom: “Caster plant of one’s own backyard is not fit for medicinal use” (p89). And this makes one wonder if Karuna was anyway indifferent to Koteswaramma’s emotions. Nevertheless, this observation revealed her honesty in narrating the ‘self’.

1.14 Koteswaramma’s Amma Too Deserted Her

Watching the plight of Karuna, Koteswaramma’s mother was bed-ridden. She, losing heart, refused to eat saying, “I want to die before Karuna. I am tired of watching your miseries. I have no energy left to witness more.” Reacting to her, as Koteswaramma said, “If you too go away, who will wipe my tears?” she replied, “You appear to have born to cry all through the life”.

One day the old lady, calling Koteswaramma to her bedside said: “Amma, I don’t want to live any longer, will die. Your brother cannot come from America to perform my funeral rites. In the tradition of your party, remember me in a memorial meeting. Announce in it that Anjamma wanted the party to unite and work together. In memory of me, give the amount of 2000 that I saved with Nageswararao equally to both the wings of the party.” Within a week of this conversation, she died leaving Koteswaramma to her own fate.

1.15 Koteswaramma’s Daughter Ditched Her

After a couple of years, not being able to put up with the loss of her husband, Karuna too deserted Koteswaramma by committing suicide, leaving a message for her mother: “I am doing injustice to you and children; brother too did injustice to you. Believing in us you lived all along, but we both ditched you. Could not live any longer, want to go to Ramesh, pardon me”. Remembering the occasion, Koteswaramma wrote, “What had happened to me… with Karuna’s head in my lap, I don’t remember what I thought … cannot put that mental trauma in words.” She lamented: “my amma who married me off is not around… children born as the aid memoirs of that marriage are no more with me…is my very marriage a dream…?”

1.16 Seetharamaiah’s Wish to See Koteswaramma

After the death of Karuna, she came to know that the aging Seetharamaiah was expelled from the party that he had founded. In his attempt to float a new party as he came to Gudivada, police arrested him. One day, a relative of her came to Koteswaramma and said, “Seetharamaiah wants to see you. If you come, I shall take you.” Her reply was: “He wants to see me, so what? …. Shouldn’t I too desire to see him? Since I don’t want, I won’t come.” That is her clarity of issues and her concern for Swabhiman—self-respect.

Later, she heard about his release from jail on health grounds and about the onset of dementia and his poor health status. At this stage she made an expression that merits attention: “By then I have no interest… neither love nor hatred towards him… In the beginning I used to wonder: how cruel of him! But as the days passed on … I started

wondering even if he were any happier?’” This reflection reveals her looking at the life and its happenings in quite a detached fashion.

Later three comrades whom she respected as her brothers came and pleaded with her that she must visit Seetharamaiah once. Refusing to it she, like a true Marxist, questioned them: “As true communists, you should have questioned me … indeed should have reprimanded me if I were to, as an orthodox Hindu woman guided by Manusmriti visit the deserted-husband; instead, you are asking me to visit him … how strange!” But finally, they, convincing her, took to him. He cried as soon as he saw her. She questioned him: “Why do you cry? Crying for you, for your children, for food, for support … for all these years, my eyes have dried out long back. Your eyes could still shed tears?” Hearing it he cried more.

Here she narrates her feelings thus: “Seeing him cry, I could not withhold my crying. It’s after 36 years of his leaving me in the middle of night, I am again seeing him today amidst his friends. How strange life is!” In this whole episode, she sounds more philosophical.

Seetharamaiah wanted to live with her, but she dismissed it. Later, as a true Marxist, she went and lived in the old-age home in Hyderabad that was set up by CPI for old comrades. Here again, she served the inmates by reading newspapers to those who could not see clearly, serving coffee/tea to those who could not walk to dining hall, helping in gardening, etc.

1.17 Is This the Promised End?

On hearing Seetharamaiah’s death in Vijayawada, Koteswaramma was devastated. She went to Vijayawada. On seeing his lifeless body, as many reminisces jostled her mind, she cried: “Ignoring family, leaving kin to their own fate, you expended your life on people and revolution calling them as your true kith and kin. Today, who took care of you? At your death, it is your granddaughter who took you under her care.”

Staring at his dead body, she wondered; “Is this all about life? In his 80 years of life, he spent 60 years in the revolutionary movement. Underground life, jail… hardly for 20 years he was outside of it. How is it none of his party colleagues turned up to see him? Are they to abandon him because he differed with them? Long ago, Seetharamaiah abandoned me stating that I did not suit him. Now, they abandoned him. Is this what life is about?” Wondering who will bring revolution that Seetharamaiah aspired for to establish equal society, she offered her salutations to him who initiated her into communist movement.

Despite being completely worn-out from within due to the betrayal of Seetharamaiah, her husband, it is with immense kindness and patience accepting the reality with no ill-will towards anyone, Koteswaramma could bid him adieu saluting him for the last time. And it is this forbearance of her, which a reader comes across repeatedly in the narration that makes one’s respect for the narrator’s character grow enormously.

2. Discussions and Conclusion

It is said that a good autobiography, like any good literature must come from within and we see this phenomenon reflecting in Koteswaramma’s biography. Time and again, Koteswaramma, as a child-widow, a child-freedom fighter, a remarried young woman trying to build a family, a communist party-activist, an underground activist of Communist party, a deserted-wife, a student at the age of 35, a mother who lost her son in police encounter and daughter in suicide, all rolled into one integrated self, a self that personifies idealism, sacrifice, endurance, and hope, waged a relentless battle against the odds of life in a stormy terrain all alone.

Her narration, unlike that of men, zooms in on private, delicate, and emotional moments of a woman. Particularly, her narration about the underground life of banned communist party women workers in the dens tells us about their silent

sufferings that are peculiar to women alone. It also reveals how dreadful the very thought of desertion and loneliness was for a woman, and be it a revolutionary, or otherwise, how difficult it was for a woman to live without sustenance.

Indeed, there were moments of despair in her long journey of struggle. In one such moment she did ask her mentor, P Sundarayya: “What will I achieve by living?” (p 95) Sundarayya replied her thus: “You might not be able to do any good for the nation but you will certainly not do any harm for the nation. And today, the nation needs more of such people who will not do any harm to the nation.” Perhaps, this advice, which we notice her recalling once in a while appeared to have kept her in good stead. In a way, her ‘self-narration’ thus deserves to be labeled as an autogynography.

Psychologists, sociologists, and philosophers have been saying often that we are each not one, but many (Lawrence, 2018). Angyal (1965) stated that the mind is made up of a multiplicity of selves. He proposed that the “mind is made up of subsystems which interact, resulting in setting and shifting sets, as one after another subsystem takes over control of the mind and which sometimes conflict, resulting in symptoms of pressure, intrusion and invasion”. In recent years, Rowan (1990) and Lester (2010) have forcefully proposed that the mind is made up of multiple selves. In the extant autogynography, Koteswaramma lucidly traces the inner journey of her ‘self’ that takes different stands at different stages, as stimulated by the circumstances. For instance, when Koteswaramma, a revolutionary to the core, learned that her son, a student of REC, Warangal, was actively participating in Naxal-movement, forgetting her past, as a mother, requested Tarimala Nagireddy to advise her son to participate in the movement without quitting his engineering course. But when Nagireddy, smilingly, declined to take forward her request, she remained silent. This perhaps, is what Angyal (1965, 1941) meant when he said that “life is a continuous interplay of organismic trends and the ‘foreign’ influences of the environment.” Inferring from these most general patterns of ‘person-world’ interactions, Angyal proposed two human trends: one, ‘trend toward increased autonomy’, or mastery and two, ‘trend toward harmony’, or love. In the former, one strives to impose one’s control on the environment and under the latter, one seeks harmonious participation in something larger than oneself. We see both these trends in most behaviour, but usually one predominates the other. Extrapolating this theory to Koteswaramma, we can conclude that she, as a mother, first wanted to influence the behaviour of her son through Nagireddy but when learned that it is not possible, she, as a rational woman, rather preferred to accept the reality and surrender to it.

We witness such conflicts being faced by her all through the journey and whenever she could not master them, she simply ‘resonated’ with them. This could be one reason why she could move forward in her relationship with others rather than getting stuck. Even in the case of her estranged husband she, pondering over the happenings, could philosophize thus: “By then I have… neither love nor hatred towards him… But as the days passed on … I started wondering even if he were any happier?’” The same explanation holds good for her letting the children stay with their father, for what she loved more was their education vis-à-vis immediate gratification of her motherly urges.

Poignantly narrating these inner struggles, she projected her ‘self-assertion’ and ‘self-display’ quite artistically. The portrayal of her self-exploration not only made her political ideology very clear but also her very value-system to the reader. Through this narration she defined her ‘self’—a self which in the words of Radha Krishnan (1937) is “a teleological unity” having its own “life’s star, its main purpose…”—and its “attainment of ends”, which ultimately puts Koteswaramma on a pedestal as Koteswaramma—no more as a mere wife of Seetharamaiah.

This liking for the ‘harmony’ with the external world appears to be well rooted in Koteswaramma’s personality. Her emotional connection with the communist movement and its participants is so strong that her narration clearly delineated the highs and lows of the movement, the sufferings that the ordinary activists have undergone so vividly that it indeed archives the first wave of communist party’s revolutionary movement in Andhra, with authenticity, for the posterity. Even her choosing the title, Nirjana Varadhi (abandoned bridge on which three generations of patriots walked on in either direction, but today there are none, except Koteswaramma), speaks about her belief in the ‘inter-dependence value’ in developing relations with others. Though the party that she worked for long had broken into many splinter groups, she strongly wished for their working together against the social injustice, as is indicated by her sending levy for both the major wings—CPI and CPM. Indeed, this ‘self-narration’ serves as an authentic sociography throwing light on how even among the so-called communists casteism, male chauvinism, and cravings for extramarital-affairs, etc., were as prevalent as in the rest of the society.

Koteswaramma was revolutionary to the core. Her political concerns blended seamlessly into her narration sans any gender-driven consternations. As a communist of the old order, she valiantly fought for the rights of women and the marginalized sections of the society for over eight decades. Her personality is an ideal of self-sacrifice. Her life is an epitome of the struggle between a woman and her fate. She relentlessly fought against adversities of life and moved forward indefatigably, which at times touched the heights of tragic grandeur. Yet, she never lost her composure. She, unlike her deserted-husband, conducted herself true to the spirit of Marxist ideology all through.

At every stage we notice her being grateful to the people who guided her through her life-journey, besides throwing her lot for the good of others with no reservations, and it is these two traits that appear to have enabled her to maintain good network of relations, which incidentally, confirms Cavarero’s configuration of the narratable self in ‘I-you-we’ network of relations. It is this philosophy of her life that perhaps, made her able to never express any rancour or ill-will towards anyone in her narration. She did not mention even the name of the woman for whose sake Seetharamaiah deserted her. It is however, not clear from the narration, if she had omitted her name to protect her privacy or felt that her name is not worth uttering by her.Here, a question emerges: Is her biography an honest narration? The answer is,

perhaps, ‘Yes’, for at one or two places, she silently expresses her discomfiture (p77, 89) about her own daughter’s behaviour. Now the question is: How could she maintain this composure? One probable answer that emerges from reading her narration is: She found happiness in the pursuit of her value-system.

Olney (1972), in his preface to his book, Metaphors of Self, stated that autobiography matters most to us “because it brings an increased awareness, through an understanding of another life in another time and place, of the nature of our own selves and our share in the human condition.” This autogynography is one such, which, by moving beyond its actuality and historicity, is sure to advance a reader’s understanding of the question, “How shall I live?” and in that capacity, it stands out as valuable literature.

References

*Based on a talk delivered as a Panel Speaker at the Two-day International Conference on ‘Multiple Selves in Multiple Texts: Life Narratives in South Asia’ held at Central University of Jammu, Jammu on 6-7 November 2019.

30-Oct-2022

More by : Gollamudi Radha Krishna Murty

|

Thank you Professor, thank you very much. It is the life and the narration of Smt. Koteswaramma that was so captivating … nothing of mine. It’s so nice of you Professor Chandra Mouli garu to say so many good words….. |

|

In my response I used the term 'text' to refer to your article sir.Perhaps, it may not be appropriate. I didn't feel like using the term 'article' to refer to your brilliant analysis and views shared.Best regards. |

|

Once I started reading the text, I could not stop till I reached the last line.What a captivating assessment,expression and passion for sharing information,sir!Thanks for a perceptive presentation.Long ago a friend confided that children of communists and creative writers hate their fathers / mothers most for their selfishness, bandied around as 'commitment.' ]. Smt Koteswaramma's life is an example.I doubt not her integrity. Salute her spirit to remain a fighter. |