Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

A New Capital – A visible symbol of British supremacy over India was New Delhi – the 'New' being added to distinguish it from the older cities that preceded – the last and most famous being the walled city of the Mughal emperor. One major imperative for the new city, of course, was that it had to surpass in all respects its predecessor.

A New Capital – A visible symbol of British supremacy over India was New Delhi – the 'New' being added to distinguish it from the older cities that preceded – the last and most famous being the walled city of the Mughal emperor. One major imperative for the new city, of course, was that it had to surpass in all respects its predecessor.

New Delhi is thus a strange but wonderful story – of an Empire in its heyday, but also of an Empire that would soon crumble. A search for a monumental and imperial architecture, but also an architectural vocabulary that would be representative of the subcontinent.

And Robert Byron, traveling through India in the 1930s, would say:

The traveller drives out of Old Delhi, past the Jama Masjid and the Fort. A flat country – brown, scrubby and broken – lies on either side. This country has been compared with the Roman Campagna: at every hand, tombs and mosques Mogul times and earlier, weathered to the color of the earth bear witness to former Empires. The road describes a curve and embarks imperceptibly on a gradient. Suddenly, on the right, a scape of towers and dome is lifted from the horizon, sunlit pink and cream dancing against the blue sky, fresh as a cup of milk, grand as Rome. Close at hand the foreground discloses a white arch. The motor turns off the arterial avenue, and skirting the low red base of the gigantic monument, comes to a stop. The traveller heaves a breath. Before his eyes, sloping gently upwards, runs a gravel way of such infinite perspective as to suggest the intervention of a diminishing glass; at whose end, reared above the green tree tops, glitters the seat of government, the seventh Delhi, four square upon an eminence – dome, tower, dome, tower, dome, red, pink, cream, and white washed gold and flashing in the morning sun. The traveller loses a breath, and with it his apprehensions and preconceptions. Here is something not merely worthy, but whose like has never been. With a shiver of impatience he shakes off contemporary standard, and makes ready to evoke those of Greece, of Renaissance, and the Moguls.

History

George V used the occasion of his second visit to India, and the great Coronation Durbar that followed, to announce the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi. This decision was of both strategic and political significance. Delhi was not only more central to the Empire's increasing influence over the subcontinent, but it was also the symbolic head of government for centuries. To shift into an existing city, however, was out of the question – the new power demanded a new city. Planning for the new capital had begun well before the actual shift, and addressed questions of urban planning and an appropriate architectural style. (Image showing an ariel view of Rajpath)

George V used the occasion of his second visit to India, and the great Coronation Durbar that followed, to announce the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi. This decision was of both strategic and political significance. Delhi was not only more central to the Empire's increasing influence over the subcontinent, but it was also the symbolic head of government for centuries. To shift into an existing city, however, was out of the question – the new power demanded a new city. Planning for the new capital had begun well before the actual shift, and addressed questions of urban planning and an appropriate architectural style. (Image showing an ariel view of Rajpath)

In Britain, a relatively little-known architect, till now specializing in country houses, managed by dint of enterprise and family connections to become the forerunner for the new capital team.

In Britain, a relatively little-known architect, till now specializing in country houses, managed by dint of enterprise and family connections to become the forerunner for the new capital team.

His name was Edwin Lutyens.

Together with his friend Herbert Baker, Lutyens appropriated to himself the task of creating an architecture fitted for the Raj, contemptuous of what had passed before as architecture, both by Indian dynasties and by his British colleagues.

Together with his friend Herbert Baker, Lutyens appropriated to himself the task of creating an architecture fitted for the Raj, contemptuous of what had passed before as architecture, both by Indian dynasties and by his British colleagues.

Planning inspiration came from other imperial models and new capital cities: the Paris and Champs-Elysées of Baron Haussmann, Wren's unbuilt plan for London, as well as L'Enfant's plan for Washington DC. Other planning ideas came from contemporary British experiments in urbanism: the Circus at Bath for Connaught Place, and Hampstead Garden City for the residential suburbs of New Delhi.

Architecture and Symbology

The New Delhi town plan, like its architecture, was chosen with one single chief consideration: to be a symbol of British power and supremacy. All other decisions were subordinate to this, and it was this framework that dictated the choice and application of symbology and influences from both Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim architecture.

And so, while many elements of New Delhi architecture borrow from indigenous sources, they have to fit into a British Classical/Palladian tradition. Lutyens was openly scornful of 'experiments' in developing an Anglo-Indian style that had preceded him, such as the ones at Bombay and Delhi. Indian architecture, for him, was nothing better than random spurts of inspiration, but had not much of a style to emulate or to be inspired from. If, in fact, there were any indigenous features in the design, these were due to the persistence and urging of both the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, and historians like E.B. Havell.

Divided Responsibilities

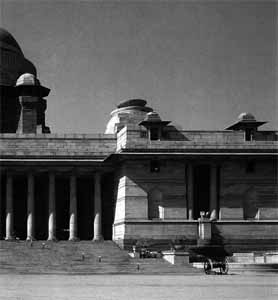

Responsibility for the plan rested chiefly with Lutyens, the more so after a dispute with Baker over the exact location for the Viceroy's house. However, in terms of architecture, the division of labor was more exact: the Viceroy's house was Lutyens', with Baker were the Secretariat buildings. Together, Lutyens and Baker, in the Viceroy's House, and what are today known as North and South Blocks, created one of the most monumental public spaces of the 20th century. This was also the origin of the dispute between the two: for Lutyens, the steep slope towards Raisina Hill would obscure 'his' Viceroy's House for some time, while for Baker a gentler slope would undermine his conception of the Secretariats. Baker would eventually have his way, but the professional discord would undermine the friendship between the two men.

Responsibility for the plan rested chiefly with Lutyens, the more so after a dispute with Baker over the exact location for the Viceroy's house. However, in terms of architecture, the division of labor was more exact: the Viceroy's house was Lutyens', with Baker were the Secretariat buildings. Together, Lutyens and Baker, in the Viceroy's House, and what are today known as North and South Blocks, created one of the most monumental public spaces of the 20th century. This was also the origin of the dispute between the two: for Lutyens, the steep slope towards Raisina Hill would obscure 'his' Viceroy's House for some time, while for Baker a gentler slope would undermine his conception of the Secretariats. Baker would eventually have his way, but the professional discord would undermine the friendship between the two men.

India Gate

India Gate

(All India War Memorial Arch, 1921-1931)

Conceived originally as a memorial to fallen Indian soldiers in the service of the British army, India Gate was originally called the War Memorial Arch, and designed after its predecessors, the Arc de Triomphe and Porte St. Denis in Paris. On its walls are inscribed the names of 60,000 men who fell fighting for the British empire. A politically appropriate monument, the archway also completed Kings Way (now Rajpath), the monumental central axis of New Delhi.

The Legislative Building (Parliament House)

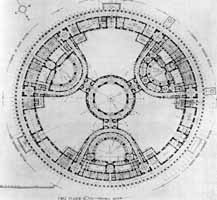

The Montague-Chelmsford reform of 1919 brought a certain legislative responsibility upon Indians, and with it the need for a legislative building as part of the New Delhi complex arose. Parliament House in its final form was Baker's conception, an odd circular form in a predominantly orthogonal planning scheme. In spite of the difficulty of citing a circular building in the urban plan, Baker creation is not without architectural merit, with an imposing exterior colonnade and an interior three-pointed plan with a central, domed space.

The Montague-Chelmsford reform of 1919 brought a certain legislative responsibility upon Indians, and with it the need for a legislative building as part of the New Delhi complex arose. Parliament House in its final form was Baker's conception, an odd circular form in a predominantly orthogonal planning scheme. In spite of the difficulty of citing a circular building in the urban plan, Baker creation is not without architectural merit, with an imposing exterior colonnade and an interior three-pointed plan with a central, domed space.

Princely Residences

For the Indian princes, a house ('palace') in the New Delhi scheme was an indicator of their prestige. (That this prestige was mostly on paper was a fact that would be painfully clear soon after 1947). The princely houses in New Delhi – Hyderabad, Baroda and Jaipur among others – were more symbolic than actual representations of power.

The biggest of these was Hyderabad House, for the Nizam of Hyderabad, perhaps at the time the richest man in the world. Lutyens' plan was adapted from the 'butterfly' scheme he had already employed as far back as 1902, and took care not to rival in splendor the Viceroy's residence. More clearly classical in origin than the Imperial buildings, Hyderabad House is less ornate and yet more original as a typology.

At Baroda House Lutyens chose, with the full approval of his British-educated client, not to indulge in any concessions towards Indian motifs and traditions. Baroda House is Anglo-Saxon in aspect and finishes, and here the butterfly plan is cut in two in the center.

Churches

Although Lutyens dreams for a great cathedral were never realized, other churches came up around New Delhi. One of these, the Garrison Church for Delhi Cantonment (Architect: Arthur Shoosmith) would be a forerunner of the modern architectural movement in India). The other, the Church of the Redemption by H.A.N. Medd, was directly next to the Viceroy's House.

Conclusion

New Delhi was an enormous political, strategic and also ultimately logistical undertaking. 700 million bricks, 100,000 cubic feet of marble, 3500 stone dressers for the sandstone...all of these under local conditions of heat and dust, irregular power supply and water and finally the numerous and often conflicting directions from various sources of authority. A world war intervened and slowed down construction.

However, after all, 17 years of continuous construction saw New Delhi in a state ready to be inaugurated in 1931. This was a grand gala affair of dances and cocktails, of pomp and grand receptions, all celebrating the British empire's greatest architectural achievement. The impeccable geometry and order imposed by the Delhi plan on the site was emblematic of the order imposed on the world by the British empire.

What irony! In 1931, it was already clear that British rule in India was drawing to a close. Like the Raj, New Delhi was already the symbol of an age that was ending – an age of splendor, an age of Kings.

All color images under license with Gettyimages.com

05-Jun-2005

More by : Ashish Nangia