Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

The unprecedented refugee influx from West Pakistan (it is estimated that 15 million people crossed both ways!) post-1947 meant that north India’s population underwent a sudden, substantial increase, as displaced persons from what was now Pakistan poured in across the border. Most of them settled in and around the state of Punjab, with a smaller number fanning out to other parts of India – notably the Terai region in Uttar Pradesh. These people – for the most part belonging to prosperous communities in West Punjab – found themselves without jobs, homes and food. With nothing to lose, the refugees rebuilt their lives from scratch – and their dynamism and work ethic became legend in the time to come.

But first there was work to be done.

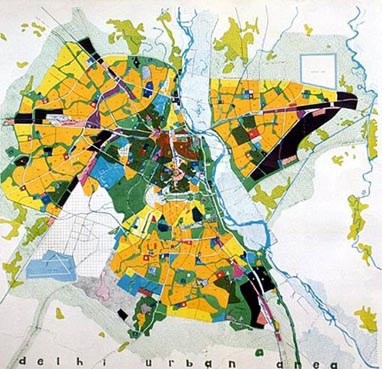

The city of Delhi at this time consisted of the following parts: the old walled city of Shahjahanabad, already bursting to the seams; the Civil Lines where British civilians and their Indian staff had lived; and the administrative capital of the British empire in India – New Delhi. To this list must be added the outlying areas, the Delhi ridge and the localities around the Yamuna, which were home to numerous villages and small towns that served as the agricultural hinterland for Delhi.

The city of Delhi at this time consisted of the following parts: the old walled city of Shahjahanabad, already bursting to the seams; the Civil Lines where British civilians and their Indian staff had lived; and the administrative capital of the British empire in India – New Delhi. To this list must be added the outlying areas, the Delhi ridge and the localities around the Yamuna, which were home to numerous villages and small towns that served as the agricultural hinterland for Delhi.

07-Aug-2005

More by : Ashish Nangia