Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

Reflections on the Validity of ‘modern’ Architectural Histories

Questioning Classification and Category

The last half-decade of architecture in India is often lumped under the heading of ‘Modern Indian Architecture’. This convenient historical classification can be misleading in more ways than one – firstly, the word ‘modern’ is somewhat of a misnomer, and when applied to post-independence architectural history is even more questionable.

‘The Modern Movement’ in a historical sense refers to an approach and a way of thinking – not just about architecture, but also in a larger sense of the term as a representation of society and its values. It is distinguished from ‘ancient’ or even ‘mediaeval’ by its appreciation and recognition of the complexity of the world and its diverse components, a tacit faith in science, technology and most importantly, a belief in the power of rational thinking as an agent of change in the world. When applied to architecture, ‘modernism’ is a concept that embraces reason as a methodology of architectural production, that the needs of society can be analyzed a perfect outcome guaranteed. Conversely and as a corollary, architecture can be an agency of change, a belief that means, in essence, that a perfect society can be engineering by the medium of a perfect built environment.

These concepts, of course, have been discredited in the last few decades because of the inherent authoritarianism associated with them. What is a ‘perfect’ society, a ‘perfect’ individual, and by consequence, a ‘perfect’ building? The quest for a single ‘perfect’ identity leaves no scope for evolution or change, and shows little sympathy or tolerance for difference and diversity.

The Case of India

These concepts are of paramount importance in a multicultural and multilayered society that is India. A heterogeneous mix of identity, class, religious beliefs and customs, layered by a history of more than two thousand years, the question of what is ‘Indian’ is not a simple one to answer. It is not surprising, then, that it becomes truly difficult to choose representative examples of Indian architecture – for the question of what to represent is one that has not yet been answered with any success so far. Perhaps this is not such a bad thing, for as soon as we tie down and fix a single identity, we capture and fix ourselves as a society in a single image, and all attempts to preserve that (possibly imaginary!) image are doomed in a world that is rapidly evolving.

Having said that, the choices the historian faces are not easy. The traditional method of writing architectural history has been firstly classification and periodicity, and secondly, to choose representative examples of each of the categories thus produced. Following this method, the following classification could be legitimately made of post-Independence Indian architecture:

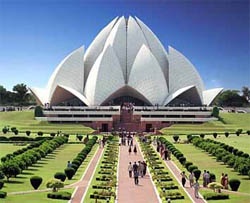

The categorization above is perfectly reasonable except for one thing : there are few buildings that fall into such neatly defined categories. For example: where would one classify the ISKCON or the Ba’hai temples? As religious buildings? It is true this is their primary purpose, but they also equally represent other things – the pluralism of religious belief in India, the wealth and power associated with successful and mass religious appeal, exercises in political wrangling and bureaucratic procedures, associations of each of these movements with social agendas – the list can go on.

The categorization above is perfectly reasonable except for one thing : there are few buildings that fall into such neatly defined categories. For example: where would one classify the ISKCON or the Ba’hai temples? As religious buildings? It is true this is their primary purpose, but they also equally represent other things – the pluralism of religious belief in India, the wealth and power associated with successful and mass religious appeal, exercises in political wrangling and bureaucratic procedures, associations of each of these movements with social agendas – the list can go on.  Once again, how would one classify buildings such as the Bombay Stock Exchange or the New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) buildings? Once again, a more traditional classification as institutional buildings does not adequately represent the complexity of the symbology that these structures communicate.

Once again, how would one classify buildings such as the Bombay Stock Exchange or the New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) buildings? Once again, a more traditional classification as institutional buildings does not adequately represent the complexity of the symbology that these structures communicate.

13-Nov-2005

More by : Ashish Nangia