Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

What is the vernacular? Does it mean the architecture of villages and remote settlements, or is it simply defined by its opposition to the ‘modern’ or ‘designed’? These questions, especially in the context of India, are not easy ones to answer. The vernacular can be simply defined as

“of, relating to, or characteristic of a period, place, or group ;

especially : of, relating to, or being the common building style

of a period or place”

Though this definition is better applied to Western culture, more so in the context of North America, where the ‘vernacular’ often denotes pioneer construction and architecture, or the shingle style, or even the forest construction of New England and the Rockies. The ‘vernacular’, in India, denotes low cost, traditional village and small town settlements, where construction is carried out without the help of architects and professionals, where building activity is regulated by a long tradition that stretches back for many centuries, in many cases.

Vernacular settlements in India often take on the shape and form that is dictated by the climate they are in, or the socio-cultural norms that they are designed to preserve and protect. For example, village settlements in Uttaranchal are often characterized by houses of stone, timber and mud mortar on slopes, with thick stone walls of coursed rubble masonry designed to ward off cold, with a shelter for animals below the main house (the heat given off by mulch animals heats the house above further). In Kerala, village houses are slope-roofed with Mangalore tiles and thatch to draw off and channel rain. In Assam, the same houses are often built on stilts, the better to counter the often damp ground. In Punjab, whitewash on the outside walls helps to cool down the summer heat.

Houses near Benares showing settlement patterns in harmony with the environment.

The list could go on, but in each case we see that vernacular architecture in India’s diverse regions has evolved a unique way of responding to the climate and the environment that is sustainable, shows an intelligent approach to the problems of climate, and is a delicate balance of social and cultural factors through spatial vocabulary such as walls, courtyards, floors and semi-private and private spaces.

Climate, of course, is a predominant factor in determining the forms of vernacular architecture in India. Climate in India varies from the scorching sun in the Gangetic plains to the tropical conditions of the south, from the dry cold climates in Spiti and Leh to the perennially damp conditions in the northeast of the country. This variation in climate spawns a diversity of forms for vernacular architecture.

Apart from climate, geography too is a determining factor. Geography, once again, can vary from the hilly terrain of the Himalayas and Kashmir, to the flats of the Deccan and the south, from the damp ground of Assam and Bengal to the dry earth of Punjab.

Vernacular Construction in Kerala.

The third factor is the availability of material and the types of material available. In Goa and Karnataka, an abundance of red laterite stone makes this the medium of choice for vernacular construction, and in north India a clayey soil makes sunburnt bricks and mud mortar a commonly used medium. Bamboo construction can be found in the northeast, and roofs tiled with the so-called ‘mangalore’ tiles in the south. Similarly, a plethora of sandstone made medieval Jaipur into the famous ‘Pink City’, and a similar stone was used to face Mughal buildings in the 17th century.

An interesting theory holds that materials could also vary according to the caste system. White stone is apparently only used by Brahmins, red by Kshatriyas, yellow by Vaishyas and black stone by Shudras.* While these classifications may be history in the new India, there is much to be gained by evaluating these claims more closely.

Vernacularism in architecture has been upheld as a modern value, a tradition to be observed while designed for the new age. Followers of vernacularism as a building tradition have been many : amongst the most famous international examples has been that of Hassan Fathy (1900-1989), who in his numerous projects in Egypt replicated and rediscovered building traditions of the region that were thought to be dead, giving them a new meaning and relevance. Similarly, Le Corbusier, that most avid of Modernists, rediscovered the magic of the vernacular in his later projects such as the Rob-et-Roq housing, the monuments at Chandigarh, and the chapel at Ronchamp.

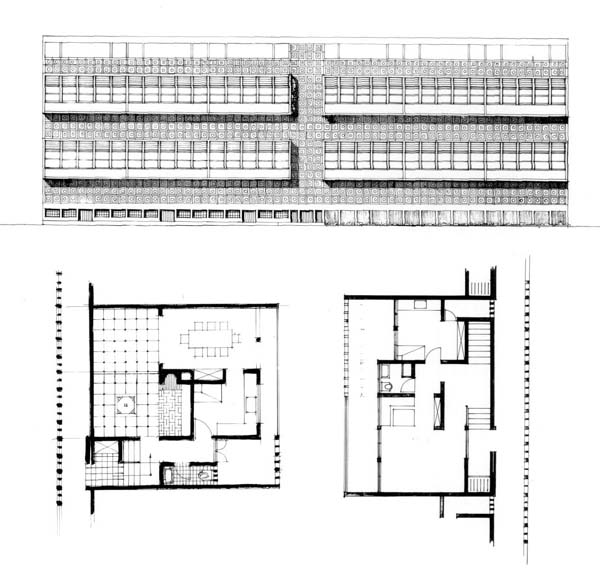

Iraq Refugee Housing, by Hassan Fathy.

Aranya Housing, Indore, by BV Doshi. Village in Spiti.

The climate is cold and dry.

19-Jul-2009

More by : Ashish Nangia

|

must read ths...... pls go through... superb atricle.... |