Nov 01, 2025

Nov 01, 2025

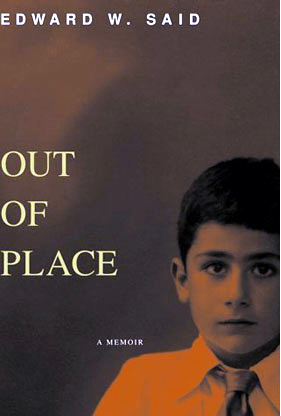

If only Edward Said had also been a novelist. That was the spontaneous reaction the reading of Out of Place elicited in me. How memoirs could be elevated to highest literary form Said amply displays in this book written during a period of illness when lesser souls would have had difficulty finding the center alignment of which along with undulating waves of current to plumb and traverse the deepest and ineffable truths is essential.

If only Edward Said had also been a novelist. That was the spontaneous reaction the reading of Out of Place elicited in me. How memoirs could be elevated to highest literary form Said amply displays in this book written during a period of illness when lesser souls would have had difficulty finding the center alignment of which along with undulating waves of current to plumb and traverse the deepest and ineffable truths is essential.

Not only does he give us an insight into the intellectual development that took root out of seed buried under the ground of ‘Edward’ or ‘Ed’ the exterior self and finally manifested out in the open under sun but also install us in a world which loves history more in streets than on pages of the books.

As Said recounts his early life and takes us back and forth between Cairo, Jerusalem, Palestine, Lebanon and US we bear witness to a personality for whom nothing but absolute truth and its articulation at all possible levels hold the paramount importance. Said, the writer of this memoir, has triumphantly been able to detach himself from his Self depicted in memoir and be a narrator watching everything with his mind’s eyes and giving it a textual shape in a language which not only justifies the visuals but also their whole architecture. So close does he take the reader to other characters that one ultimately has the sense of scrutinizing them from multiple angles.

Memoir delineates an intellectual development that if drawn on a chart is nothing but a straight line making 45 degree angle to both the axis. A taciturn exterior fanning the flame inside by careful observations, a rebellion streak weaved with rational thought, a musician coming to terms with his shortcomings, a son torn between contradictions of his parents, a native bearing witness to the abandonment of past, an outsider stranger to his adopted home and then the home he ‘accorded stability’ and emergence of an intellectual not far from politics arisen out of heart.

Though Said’s imaginational faculty can be gauged early in childhood when the child Said reveled in playing with the characters of Greek myths by making them do things they did not do in originals and stretching the stories of movies (Arabian Nights, Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan series, Laurel and Hardy etc) past their formal endings subsequent schooling did little to nourish it and we see an ‘Edward’ who was constantly on the receiving side of teachers.

During the Cairo years of education first in GPS (Gezira Preparatory School) “very little of what surrounded me in the school - lessons, teachers, students, atmosphere - was sustaining or helpful to me”, then in Cairo school for American children (CSAC) “where I stayed through the academic year 1948-49, got smaller and less challenging as I moved up through the ninth grade”, Said wrestled with what he thought he was and others wanted him to be. This gets expressed in this sentence, “I generally consider my real or best self -undefined, free, curious, quick, young, sensible, even likable- from ‘Edward’, inescapable and doomed self, never quite right, and indeed very wrong and out of place.” Only at St. George’sSchool in Jerusalem did Said feel at home for the first and last time in his school life for amongst the boys who were like him, Arabs. Then, after showering encomiums on one mathematics teacher, Said goes on to say, “as I look back on it fifty years later, a general sense of purposeless routine trying to maintain itself as the country’s identity was undergoing irrevocable change” alluding to the events of 1948 which led to Arab exodus from Jerusalem. At Victoria College Said, “risen to a kind of bad eminence as a rabble-rousing troublemaker” and was almost thrown out.

It was only in US at Mount Hermon School which Said joined in 1951 did he begin to find an intellectual in him, “what developed in my encounters with the largely hypocritical authority at Mount Hermon was a newfound will that had nothing to do with the ‘Edward’ of past but relied on the slowly forming identity of another self beneath the surface.” When Said wrote an essay assigned by one of his teachers and turned it in to his utter surprise the teacher analyzed Said’s work in a way which Said had charged. “For literally the first time in my life a subject was opened up for me by a teacher in a way that I immediately and excitedly responded to, Said writes. But the oddness of a Christian, a non American American and a non Arab Arab from Cairo that kept clamoring ‘out of place’ remained intact. Quite positively Said ascribes his intellectual development to this absence of home, “incentive to find my territory, not socially but intellectually” which was to remain with Said through out his life till his last breath.

The toughness that timid ‘Edward’ was to acquire in his early US years are best expressed in the confession, “by the early spring of 1952 I had suspended my feelings of paralyzed solitude-missing my mother, my room, the familiar sounds and objects that embodied Cairo’s grace-and allowed another less sentimental, less incapacitated self to take over.” Finally the experience of Mount Hermon is summarized by Said, “I never lost my sense of dislike and discomfort at Mount Hermon, but I did learn to minimize its effect on me, and in a kind of self forgetting way I plunged into things I found it possible to enjoy. Most, if not all, were intellectual”

This was the making of an intellectual self the sharpening of which never stopped. And this change was so overwhelming that Said felt weaned away from “Cairo habits of thought, behavior, speech and relationships.” Not only did ‘speaking and thinking’ undergo a radical change taking him further away from Cairo but also made even the existence of his sisters in US for college studies ‘utterly remote and alien.’ As a student first at Princeton and then at Harvard Said further chiseled his intellectual faculties by transcending way beyond what the regimen required. Now ‘Ed’ was Said.

Said dwells a great deal on his relationship with his parents which for his utter love for them must have been a soul cringing experience. He lays bare down to last shred all the frailties of his parents in a manner the detachment of which lends the anecdotes and observations tectonic dimensions. As a domineering figure, physically as well as mentally, his father a US citizen passport holder who had served in American Expediting Force in World War 1 and a man with great business acumen was an impediment to his becoming a freewheeling personality and also a source of strength to fight the adversities. He almost launched a mission to reform Said’s physical self and even had him wear trusses on his back. As a consequence Said grew consciousness of his ‘ill formed structure.’ He would even check Said’s pajamas to make sure he had wet dreams and thus not indulging in ‘self-abuse.’ His father had evinced exemplary resilience first in the riots in Cairo during Said’s Mount Hermon days and then under Nasser’s ‘Arab socialism.’ Some words and phrases like ‘buck-up’, ‘never give up’ and ‘look at their nose’ continued to inspire Said through out his life. He remained incapable of articulating his love for Said directly all his life. His mother who he was more close to encouraged him to regularly practice piano and would read aloud Hamlet for him. Though she would tell him that he was her favorite child sometimes she would exhibit a sickly indifference.

The entire book has been weaved around the theme of loss of home and thus always out of place. Though Said adduces many incidents which were directly symptomatic of his being out of place it is his habit of visiting every place with suitcases full of clothes that alludes to his unique ability to lend the stay at new place however short with sense of permanence. Because the book deals with first twenty eight years of his life we find only some passing mention of Said’s political activities. Nor does he much dwell on his otherwise well laid out thoughts in other books and essays barring an instance when he says, ‘I was no longer the same person after 1967; the shock of that war drove me back to where it had all started, the struggle over Palestine.’ About one horrific motor accident that Said had had we hear only about how he needed his mother to soothe him but not about his feelings and pain at having heard of the casualty. Though we hear about Said’s first broken up marriage it is not even touched at much less dissected.

But whatever is inside the book makes for an exhilarating reading on account of an extraordinarily plunging into what Said felt and employs a remarkable range of imagination to this end. The act of remembrance that a memoir is has been turned into an utter meditation where almost everything that Said touches upon takes on a literary aroma that wafts around and intoxicates the reader between flipping of pages which more often than not happens slowly. The memories or even the memories of memories as traced by him down to their origins metamorphoses his personal reminiscences into the literature of highest form. It is this quality of this memoir from one of the most perspicacious intellectuals that makes it an acute microscope to see and understand his growth up close.

06-Nov-2011

More by : Pramod Khilery