Jan 08, 2026

Jan 08, 2026

Biography of a poet like that of Keats is always shrouded in mystery as his poems. Like Shakespeare’s sonnets, Mona Lisa’s smile and the Sphinx, the poetry of Keats are also ever mysterious for their objectivity and non biographical nature. Like Shakespeare, Keats also remained silent about many of the incidents of his personal life and he despised the ‘impalpable design’ in a poem. Facts of life very rarely explain the facts in the drama of Shakespeare. In a similar way, the poetic persona of his poem bleeds profusely in many poems, but Keats as a person was not such a sentimental figure at all as Nicholas Roe tried to prove in page after page of his biography of Keats. On the contrary, Keats was a sturdy youth before falling a victim of the fatal disease, tuberculosis. It is impossible to believe that Keats, a poet who discovers beauty in the midst of ugliness of life, had to take opium to forget the pains and sorrows of his personal life.

Biography of a poet like that of Keats is always shrouded in mystery as his poems. Like Shakespeare’s sonnets, Mona Lisa’s smile and the Sphinx, the poetry of Keats are also ever mysterious for their objectivity and non biographical nature. Like Shakespeare, Keats also remained silent about many of the incidents of his personal life and he despised the ‘impalpable design’ in a poem. Facts of life very rarely explain the facts in the drama of Shakespeare. In a similar way, the poetic persona of his poem bleeds profusely in many poems, but Keats as a person was not such a sentimental figure at all as Nicholas Roe tried to prove in page after page of his biography of Keats. On the contrary, Keats was a sturdy youth before falling a victim of the fatal disease, tuberculosis. It is impossible to believe that Keats, a poet who discovers beauty in the midst of ugliness of life, had to take opium to forget the pains and sorrows of his personal life.

“What imagination seizes as Beauty, is Truth” for Keats. The tragic failures of his life and love have the least effect on his poetry as his poetic motto was ‘negative capability’. He was the most objective among the Romantic poets. He could transcend the personal into the impersonal. The ‘I’ of his poem is very rarely Keats himself.

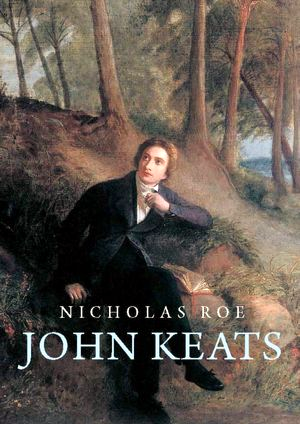

But Nicholas Roe has given us a new Keats in his recently published biography and I had to succumb to the gravitational pull of the outstanding biography in which Roe has challenged some of the conventional ideas prevalent about Keats. He pays close attention to the source of Keats’s poetry and tries to discover the mind which feels rather than the man who creates. But the book has some highly debatable areas. In the earlier biography Keats written by Andrew Motion we did not get a direct biography. Instead of a straightforward biography, Andrew Motion gives us Wainewright’s first person, fictionalized confession in his biography Keats (1999). But nowhere it is suggested in Motion’s biography that John Keats wrote famous poems under opium influence. On the contrary Motion focuses on the vigour of Keats’s character as well as his verse. He challenges the sentimental cliché about Keats that he was a sickly dreamer concerned only with art for art’s sake.

But what frustrates us in the wonderful biography John Keats: A New Life of Nicholas Roe recently published by Yale University is that he tried to give the same age old cliché about Keats. It is really painful to know that Keats was also an opium addict like Coleridge or Thomas De Quincy. But the argument that Nicholas Roe gave is not a strong one. It is chiefly a wide guess work as no mention of it is there in the letters of Keats. It is still to be ascertained that John Keats was an opium addict.

According to Nicholas Roe, Keats might become so after his brother Tom's death Even if one analyses only one poem ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, one can clearly understand that Keats despises taking anything that is related to intoxication. The poem 'Ode to a Nightingale' begins with the pictur of 'drowsy numbness' and Hemlock drinking. But we should not ignore that the poet himself wrote in 'Ode to a Nightingale',

"Away ! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards

But on the viewless wings of Poesy".

It is true that Keats wrote in the same poem a little earlier:

"My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains."

It is very difficult to believe that Keats was an opium addict as, he himself clearly gave his preference later in the poem for 'the viewless wings of poesy'. Yes, such thoughts of taking of opium or any such drug came to his mind. So he used the word 'as though' which clearly shows that he was in two minds. But at one point in the poem, Keats gave a strong argument. Being a poet he possesses imagination and does not feel it imperative to take any sedative or wine.

Yes, the poet gave ever sensuous description of wine in the poem:

"O, for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim

And purple-stained mouth"

Just imagine that even after giving such an ever tempting description of wine, the poet gives vent to his reluctance to take wine 'not charioted by Bacchus and his pards'.

Nicholas Roe comments that Keats became an opium addict. But that seems to be an injustice to a poet like Keats whose imagination was totally different from that of Coleridge. He was the most stable among the poets of the Romantic school. His supernaturalism was based on Greek myths and Hellenism while Coleridge's imagination was induced by opium in many of his poems such as Kubla Khan.

The new thesis about Keats's opium addiction needs to be reconsidered. Or a wrong message may reach the reader. Insightful observation and narrative clarity often lack in some scholarly work. This is also to some extent true about Nicholas Roe’s scholarly book. It reaches some harsh conclusions about the great genius of Keats without any concrete proof. Some of which may create a wrong impression about Keats and his imaginative creativity. Keats was orphaned as a boy, trained as a doctor before becoming a poet, and died in Rome at age 25.

Immediately after his death, Shelley mythologized him in the elegy "Adonais," which helped create the myth of Keats as the quintessential poet. In this original biography, however, Motion has provided a thorough examination of the social, familial, political, and financial forces that shaped the real man rather than the poet of myth.Nowhere the question of Keats as an opium addict arises. His concept of beauty is never linked to any opium inducement. Nicholas Roe’s thesis is not only a misrepresentation of a fact, but an exaggeration of a damn guesswork. In his over enthusiasm, Nicholas brought Keats and Coleridge in the same bracket.

There is a basic difference between the nature of imagination of both the poets. Poverty, talent and early death – Keats story with a doomed love affair at its heart represents an ideal passion and tragic loss. But it is only an aesthetic perception for the ever poetic soul. Even about the relationship between Fanny and Keats, too much of sentimentalisation has been done over the years. But we should not forget that Keats set off for Italy in spite of the bitterness and sorrow which ensures that a certain toughness is there in Keats. In spite of the headlong, devoted, agonized rapturous – an ideal of passion, Keats like Shakespeare in his sonnets remains more or less impersonal. Nevertheless, Nicholas Roe’s biography cannot be dismissed as a dizzy imaginative pastiche or it cannot be sent to the dusty stack of scholarly cogitation. It gives us a fresh peep into the creative mind of Keats. But we should cautiously be infatuated by some of his enticing conclusions about Keats.

23-Sep-2012

More by : Dr. Ratan Bhattacharjee

|

thanks for your appreciation Mr.B.S.Murthy. I feel privileged and cheered up by your kind words |

|

Scholarly article followed by compelling discussion. Nevertheless, the idea to try to fathom a poet's proclivities from his poetry is appreciable but yet may prove to be elusive for in 'poem' as much as in 'novel', the writer's 'examined' and and the 'experienced' tends to be fused into one creative whole. |

|

The Blackwood's Magazine projected Keats as an archetypal effeminate poet, exemplar of middle-class masculinity, and an eternally youthful object of Platonic attraction. The immediate reaction to Keats’s death, the controversy over Hunt’s 1828 biography, and Brown’s 1836 manuscript which provided the basis for the first full-length biography in 1848. Of the three, the early eulogies are least concerned with offering biographical veracity and favour Keats’s intellectual, rather than bodily, manifestations of gender. The shared immediacy of their grief, anger, and efforts to memorialize their friend effectively results in an often awkward, limited, and forced reading of Keats’s multi-dimensional masculinity.Shelley also took, perhaps, the easiest route in doing so by downplaying his subject’s middle-class masculinity. The result was a one-dimensional gendered interpretation, by critics and fans alike, of Keats as delicate, overemotional, and effeminate, more suited to poetic object than to poet himself. Aesthetic iconization of the beautiful youth becomes evident. Charles Cowden Clarke’s epistolary account of Keats’s death in the 27 July 1821 Morning Chronicle tries to create an equilibrium between a stereotypically sensitive nature so wounded by a critical review as to lose its desire to live, and “a noble – a proud – and an undaunted heart”. He emphasizes Keats’s Englishness and his love of liberty, aligning him with the ideological construct of poet as ideal statesman. He observes that “[Keats] had a ‘little body,’ but he too had a ‘mighty heart'.Brown beautifully wrote :"He was small in stature, well proportioned, compact in form, and, though thin, rather muscular;—one of the many who prove that manliness is distinct from height and bulk."As a part of Brown’s allegations against Blackwood’s, he takes particular offence to the review’s attacks on Keats’s gender performance, alleging that “They represented him as affected, effeminate, and sauntering about without a neckcloth, in imitation of the portrait of Spenser,” and dismisses this depiction as malicious “falsehood” .By insisting on Keats’s youth and effeminacy , these critics sought to disperse the Jacobin potential in his poems.According to the Burkean standards Keats’s distinctive poetic voice could be identified with stereotypes of passivity and weakness and thus accommodated to the prevailing masculine structures of social and cultural authority.Byron’s abusive remarks about Keats were also motivated by this anti-Cockney school attitude. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language is also instrumenta in giving a gendered meaning of the word ‘Cockney’ as ‘any effeminate low citizen’.He was an admirer of Leigh Hunt and Hazlitt. His vulnerable tenderness enervated the discourse of masculine authority, Hunt once the most articulate radical journalist of England was doomed by Dickens to eternal childishness, and Keats’s reputation developed in a similar manner during the 19th century.Shelley’s Adonais was also responsible no less for creating this misconception. David Masson wrote of Keats as “an intellectual invalid’.Swinburne described him as ‘vapid and effeminate rhymester in the sickly stage of whirlpool’. Wordsworth , Byron , Shelley and even Leigh Hunt concerned themselves with great causes as liberty and religion. But Keats lived in mythology afairyland the life of a dreamer , which should not be misinterpreted as effeminacy.There was effectively a continuation of polemical criticism of Feminism of Keats in Blackwood’s Magazine although his poetry was thoroughly engaged with contemporary politics.Adverse criticism of Keats obscured the ideological force in his poetry when Cockney controversy generated public reevaluation of even Wordsworth’s poetry.As part of their systematic cultural depreciation, the Cockney school essys worked further to prejudice understanding of Keats’s politics from an early date , by establishing a powerful idea of Keats as an immature poet and thinker. |

|

Wlliam Hazlitt conisidered Keats effeminate, for the very air of languishment in his poems. Let me quote from the essay 'On Effeminacy of Character' published in 1822 , a year after the demise of Keats: 'I cannot help thinking that the fault of Mr. Keats's poems was a deficiency in masculine energy of style. He had beauty, tenderness, delicacy, in an uncommon degree, but there was a want of strength and substance. His Endymion is a very delightful description of the illusions of a youthful imagination given up to airy dreams...' But he does not consider Keats' consumption, against which Keats could do little, and perhaps explains his resigned attitude and lack of expected masculine expression of, generally speaking, being in control of things. |