Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

‘Shodh’ presents a micro world of a woman where husband, ma-in-law, neighbors etc. hold a paramount position. Analyzing ‘Shodh’ was not easy for me. It is a very flat piece of writing. Thought content of a novel is its main strength. It does not mean that a novelist should philosophize unnecessarily. Actions as they are depicted and characters as they behave must evoke ideas. The words must be pregnant with something indecipherable, something beyond. Something should be left unsaid. Something must hang in the air of a novel. The reader must be compelled to respond, to identify, and to get affected. A novelist must know how to move laughter, and tears in a reader.

‘Shodh’ presents a micro world of a woman where husband, ma-in-law, neighbors etc. hold a paramount position. Analyzing ‘Shodh’ was not easy for me. It is a very flat piece of writing. Thought content of a novel is its main strength. It does not mean that a novelist should philosophize unnecessarily. Actions as they are depicted and characters as they behave must evoke ideas. The words must be pregnant with something indecipherable, something beyond. Something should be left unsaid. Something must hang in the air of a novel. The reader must be compelled to respond, to identify, and to get affected. A novelist must know how to move laughter, and tears in a reader.

Well, there is no suggestive provocation in this novel. Everything is brutally articulated in very concrete and corporeal words. That is Taslima Nasreen for us - a male Salman Rushdie. Here is a woman who does not distinguish between self, body and identity. They are one and the same for her. Perhaps it will not be wrong to call her a body obsessed woman. She is full of self-love, self-pity, and also full of revenge against the one who has violated her dignity. That is all. May I be allowed to say that she is not at all mentally challenging.

| Feminism for some is passion; for others it is a profession. I am skeptical about the feminism of those who take it as a profession. It seems our society is being torn apart by unthinking extreme attitudes. |

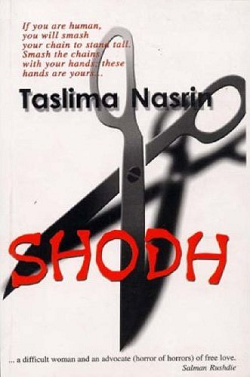

Paradigmatically the novel enforces the traditional, conservative, and quite unfair view of women. It depicts a woman as secretive, cunning, revengeful, incapable of open and bold revolt, incapable of anything except carrying on a hidden relationship with another man in order to avenge the husband’s cruelty. The novel revolves around cynical sayings like ‘Don’t trust a servant, and a husband’ or ‘men go for physical relationships without love’ and all such absurd stuff. The novel does not elevate. It reduces. It zeroes down possibilities of companionship, love and sharing. It cuts off trust, the very basis of life. The cover page shows a pair of scissors and it rightly suggests that the novel tries to tear apart faith in human goodness. Whether it does it effectively or not is a different question. But it certainly tries to do that.

The novel is about a woman Jhumur. She has done M.Sc. in Physics. She has lived very freely in her college days. She has been almost like a boy participating in party propaganda, pasting posters, roaming around. She develops a relationship with a young chap Haroon. When he proposes she postpones the question of marriage for six months. Then all of a sudden her father and family coax her into pressing Haroon to get married the very next day because her elder sister had been ditched by a boy earlier after five years of courtship. Haroon is shocked at this sudden change. But he is caught into the net and is married to Jhumur. Jhumur gets pregnant within six weeks of her marriage, a fact that fills Haroon with suspicion. He feels that Jhumur was already carrying someone else’s baby at the time of marriage and that was why she drove him to this fast matrimonial union. He gets her aborted. He puts her under a sort of a house arrest. Then he frantically tries to seed Jhumur with HIS baby. In the meantime Jhumur spots a young, burly fellow Afzal who lives downstairs. She sleeps with him carefully counting her days to get pregnant with Afzal and not Haroon. No one knows anything about it. Afzal conveniently goes to Australia after planting the seed. Haroon’s happiness knows no bounds as he thinks that the new born Ananda is HIS own baby. The revenge (shodh) is complete.

The story reminded me of one of Amrita Pritam’s short stones where the maid sleeps with the groom to avenge all insults. The maid and the daughter of the house are of the same age. They grow together but the daughter never forgets to remind the maid of her lower status. On the wedding night amidst all hustle bustle the maid slips into the groom’s room. All her life she has been eating the leftover of the daughter of the house. Now it is the daughter’s turn to taste the leftover husband. And if I remember correctly the name of the story is Joothan (left over). These are chilling tales of the revenge of the female. Whether one finds them of good taste or not depends on the personal inclination of the reader.

But then these cunning mechanisms devoid of any ethical obligation have always been part and parcel of women’s world. Why? Getting even with the family and establishing superiority have always been important to women. To inquire as to why it is so we will have to turn to the phenomena of female subjugation. Anthropologically speaking, the female of the species has a better survival instinct. Her instinct for a suitable mating partner is sharper than the male because she has been entrusted by Nature with the task of carrying the race forward. This very basic fact generates a sense of insecurity, jealousy, and doubt in men. The woman is not only a mother figure but also a potential threat to masculinity. She is capable of betraying and therefore of destroying the ego of a man.

Most men in India believe in this cunning intelligence of a woman. A simple explanation follows that all this purdah system, house- imprisonment sort of living arrangement, escorting while moving out and various other restrictions imposed on women are an expression of this basic distrust. To carry the argument further, the condition of the subjugated and confined woman is actually against the fundamental laws of Nature. But once fallen prey to these centuries’ old institutions of distrust, most women lose the power to imagine any shift from the present paradigms. So survival of a housebound woman depends on authority and hold over men- husbands and sons.

A woman in her isolation in a house develops the tools to survive, to live, breathe, create and recreate. The passage to her dreams goes through the men in her family. There is no direct access to life. Ethics or no ethics, religion or no religion, she has to withstand life. Also, the women unconsciously accept the male view of themselves. It is interesting to watch how women through centuries of practice develop a male view of themselves. Simon do Beauvoir says, ‘It follows that woman sees herself and makes her choices not in accordance with her true nature in itself, but as man defines her.’(169)

Convention has succeeded in turning women against themselves. Thus result the trends of preference for the male child in women, conniving in female feticide, demanding dowry and so on and on. This manly perception of women of their community is an alarming anomaly. Taslima is no exception. Her view of life revolves around these faded, accepted, often misplaced idioms of understanding life. She accepts the role of a woman as the prime mover in family politics. Victimization on one hand and revenge within the four walls of home on the other are the two poles between which the narrative of ‘Shodh’ moves.

Raj Kumar Santoshi’s movie ‘Lajja’ portrays a young girl played by Madhuri Dixit. She is carrying the baby of her lover. Both work in a roadside drama company. Finally the chap doubts whether the baby is HIS own or not and refuses to marry the pregnant beloved. Madhuri is broken. As the evening deepens, Ramaleela begins. The guy plays Rama and Madhuri, Sita. Rama asks Sita to go through the fire to prove her chastity. Sita refuses to comply. She says that she has been made a victim of character assassination that Rama should also go through the fire test as he too has been away from her for an equal number of days, that if she could have gone on the wrong path, so could have Rama. Ramaleela goes haywire. Madhuri decides to go on with her pregnant status. The movie, though somewhat crude, presents a more acceptable form of defiance than what Jhumur does. The answer to male distrust should be more direct and open. Anyway I cannot change the text of the novel.

If Salman Rudie calls Taslima an advocate of free love, I will call her an outright hedonist. It is shocking to see this woman’s vision not progressing beyond burly bodies and hairy chests. The body image as reflected in ‘Shodh’ calls for an urgent sorting out of the concept Body as a means of celebrating life has been an old Eastern view. We have always taken this human form to be a gift from God. Its proper care has always been one of our concerns. One whole caste (nau) in the Indian caste system is for the fine keeping of the body - massaging, oiling, perfuming. The traditional Western view, on the contrary has not been that complementary to the body. Not only that the body is considered a dirty container, it is also isolated and separated from other things. Western concept of identity formation begins when the child views her/himself as a distinct creature, different from all others. Eastern view says that the body is a formation of Pancha tatva, the five elements, namely, sky, water, fire, earth, and. wind. We have an extended identity concept where family, trees, animals, in fact, the whole cosmos participates. Therefore we do not have much problem when a woman is referred to as Ma, bou (daughter-in-law), Haroon’s wife, Habib’s bhabhi, Ananda’s mother, or Sebati’s neighbor. Taslima parrots the Western concept of identity when she says,’ I woke up with a start. No one in the house mentioned me by my name, everyone called me Bhabhi. It gave me such a thrill! I realized I had a name, an identity. His calling me Jhumur Bhabhi made me feel I was a distinct person who had gone to the university and had collected so many degrees.’(95)

Well, an Indian feminist like me wants to assert that going to a university does not mean that one is no one’s bhabhi, wife, mother, or daughter. Frankly, this is such silly business. Taslima hardly talks or hints at mental liberation, thinking and understanding. Someone utters your name, you become a distinct person. You have a liaison, you have avenged. In fact, this brand of feminism is discarding all mental cushions available to a woman in moments of crisis. Family, relatives, neighbors, and society need not necessarily be perceived as enemies.

Feminism for some is passion; for others it is a profession. I am skeptical about the feminism of those who take it as a profession. It seems our society is being torn apart by unthinking extreme attitudes. Politicians are out to encash just everything. Feminism becomes women’s reservation bill and abolishment of caste system becomes quota system. Things get distorted beyond limits. Issues are hardly recognized in their original form. Concern for Dalits is now a political tool, a tool to further wrongs. So it is with feminism. ‘Shodh’ is said to be having autobiographical elements, If so, we have all sympathy for Taslima. In fact, bitter experiences produce bitter feminists. But then a thinking mind has to decide how far it can allow the negative side of life to dictate thinking. Jhumur turns all her qualifications, her education, her exposure against her happiness, against her own self. She declares,’ Wives and daughters! Pay heed! Academic skills don’t count with the in-law.’(44)

For me, the novel registered an impression only after seventy four pages when Jhumur gets forcibly aborted. Then only I could get the preceding man hating mania. The first seventy four pages sounded almost nonsensical because Jhumur wants a highly romantic (film style) love or show of love from Haroon and does not get it. The novel begins in a fiat statement of disappointment in marriage. Nothing new, really! Life is no movie. The complaint is that the husband does not dance taking Jhumur in arms. Even worse is the fact that Jhumur compares Haroon with Dipu whom she had seen dancing taking his wife Shipra in his arms. Well, one husband can hardly be blamed for not aping another husband, of whose conduct at a particular moment he may not even be aware of. Anyway the tale drags on and so does the flimsy romantic vision. The ideal daughter-in-law is painted for us, ‘I knew I was the bou of the house only too well, hadn't dared to think otherwise even for a second, not since the time I had come to the house. I knew I had to lower my voice, reduce it to a murmur, and keep my eyes fixed on the ground so that they didn’t catch the eyes of any other person. How else could I become Haroon’s bashful wife? I had known it in my bones, what it was to be a daughter-in-law, a self-effacing, shrinking creature’.(7)

One problem with this brand of feminism is the end of such conditions as described above. We no longer have forced dress code on daughters-in-law. You no longer connect. If the argument is based on thought, it has a longer appeal.

Taslima condemns the sense of settlement in marriage. According to her one should not take the partner for granted. In effect it implies that the partner should always be kept on toes, tense and worried. There should be no mental peace. Similarly she compares the condition of Jhumur with that of the maid, Rosuni and comes to the conclusion, ‘In a sense Rosuni, the maid of the house and I, the bou, were in the same boat. Rosuni cooked so did I; she tidied the rooms, I did as well. But at times I felt Rosuni was the luckier one. She could lift her veil whenever she pleased. I had to keep my head covered, whether I liked it or not.’ (12) Taslima also has problems regarding the custom of touching feet of elders of the family. The old tradition of not calling one’s husband by name (which feels so romantically ticklish to our present sensibilities) irritates Taslima. She is, in fact, infuriated, ‘So I stopped calling him Haroon and can’t bring myself to refer to him by name even to this day my throat had become voiceless.’(37)

Sebati is Jhumur bosom friend. She is a doctor. All the patients of Sebati that Taslima refers are victims of a female’s biological fate. I could not help noting that not a single case of Sebati has any healthy, positive condition. Taslima’s brand of feminism does not leave any space for happiness. Even good things start looking bad. Our sub-continent has various ceremonies for a carrying woman. So many celebrations are held to mark different stages of pregnancy. What can be bad about these practices? But no, Taslima is angry that all the caring is actually not for the pregnant woman but for the child inside her, ‘But I know for certain that the amulet and the darud are not to wish me well; they are for the well-being of Haroon’s child’. (203)

Even a mother and her fetus have been separated here. They are differently identified. I remember Shashi Deshpande's ‘The Dark Holds no Terror’ where Saru feels so sad that she missed the ceremonies during her pregnancy as she had defied her parents and gone for love marriage. To my mind Deshpande's perception is correct. No carrying woman would want to miss the care and importance showered on her during her pregnancy. These small things are so important to the emotions of a woman. And what is a woman without emotions? Emotions, feelings, the unsaid fondness-these are the life breath of a woman's inner life. Taslima's whole view is so prosaic, rough and flat.

When we look at the revenge of Jhumur, a new face of womanhood is exposed. Jhumur cheats her husband so calculatingly. It is absolutely freezing. At the end, the same cruel husband who got her aborted, starts looking like a buffoon. She reduces him to be a puppet in the hands of her cunning ploys. Taslima writes, ‘I made up my mind to be pregnant with Afzal. I didn't want to offer Haroon a body ready to receive his sperm. I wanted him to sow his seed in fallow land and wait foolishly, a day after day, to see it sprout. I didn't have any sense of guilt about it. I wasn't a loose woman. I wasn't deceiving him. I was merely paying him back.'(147)

Taslima does not forget to drop a sentence here, a sentence there that may vaguely be constructed as blasphemous. 'I never learnt how to ask Allah to grant me personal favors.'(105) or 'But I doubted whether reading the Koran would help.'(137). After all, it is these sentences that have made Taslima an international celebrity, a champion of free expression, free love and what not. One cannot resist thinking that courting controversies is a deliberate attempt to gain attention.

Reference:

1. Nasrin, Taslima 2003, ‘Shodh’ (translator, Rani Ray) New Delhi: Shrishti.

2. De Beauvoir, Simone. 1949. Paris: Gallimard.

20-Feb-2013

More by : Prof. Shubha Tiwari

|

SOME BOOKS ON TASLIMA: Taslima Nasrin - The Death Order and its Background by Peter Priskil The Dissident Word: The Oxford Amnesty Lectures 1995 women in muslim societies: diversity within unity Word. : On Being a [Woman] Writer (On Writing Herself) The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry by JD McClatchy Gender, Politics and Islam FEMINISM AND LITERATURE Critical Essays : Indian Writing in English an interesting link: http://irep.iium.edu.my/15665/ |

|

may I know any other writing which are related to Taslima............ |