Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

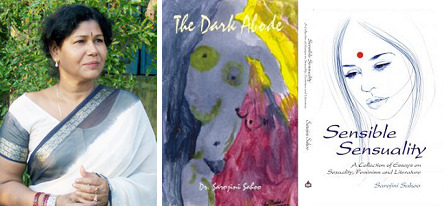

An Interview with Sarojini Sahoo

Sarojini Sahoo is a bilingual writer from the Indian subcontinent. Her writings are a rare insight into the mind of women who question the givens of patriarchal society. Sahoo offers an alternative discourse on issues related to women in India from women’s perspective. She has braved a lot of criticism for writing against the grain of patriarchy. However, her writings exemplify her philosophy which speaks of inclusiveness of peace and equality for both men and women. It has been a pleasure interacting with the author who is so approachable and forth coming with her knowledge and findings.

The Interview

Sangeeta Singh: You’ve mentioned ‘secular sexuality’ in your blog Sense and Sensuality; could you explain your take on that?

Sarojini Sahoo: Perhaps a Baul saint Lalon Fakir (1774–1890) of Bangladesh declared first the notion in his song:

“Shob loke koy lalon ki jaat shongshaare

Aar lalon bole jaater ki roop,

Dekhlaam-na ei nojore.

Sunnath dile

hoy mussalmaan

Naari jaatir ki hoy bidhaan?

Aami bamun chini poita proman

Bamni chini kishe re?”

The English translation of that song is:

“Everyone asks, ‘What religion has Lalon in this world?’

And Lalon says, ‘What the shape of religion is,

I have not seen with my eyes’.

The religion he speaks of encompasses and surpasses

not only religious identity, but also notions of gender.

‘If circumcision makes you a Muslim,

what then is the dictum for women?

If a Brahmin can be identified by his sacred thread,

how shall I know a Brahmin woman?’

asked Lalon.

Any honest, thinking person cannot ignore the blatant misogyny and barbarity of all religions towards women. The powerful Creator Gods were the product of a patriarchal, tribal, violent, intolerant society. They reflect the ignorance and brutality of that society and at the dawn of a new millennium, fundamentalists insist that we should all abide by their religious law. So, I’m always in support of the idea that a woman has no religion.

Sangeeta Singh: What I can configure is (correct me if I am wrong), women should also be able to express their sexual needs as freely as men do. Do you think it is safe for women in India to be assertive about their sexuality when the social conditions are quite contrary? The legal system in India is also not able to protect the freedom of women here.

S.S.: It’s a vague and absurd idea that woman’s right over her own body (rather we shouldn’t name it as sexual liberation) is responsible to enhance sex crime. Look at Denmark. There were six registered sex offenders living in Denmark in early 2007, according to State List. All names presented here were gathered at a past date. No representation is made that the persons listed there are currently on the state's sex offender’s registry. The ratio of number of residents in Denmark to the number of sex offenders is 357:1. But the country is very much liberal, having a less control over sexual restrictions.

In 2006, a greater number of sex crimes are registered in spring and summer, according to figures provided by the Municipal Department of Internal Affairs in Moscow. In February of that year, nine rapes were committed in the capital, whereas in March this figure reached 15, and in May, it rose to 22, and in June, it rose even higher to 23. Can we then blame seasonal effect for increasing in sex crime?

The fact is that only 20 percent of rapists are so-called sex maniacs. Another 30 percent are drunken teenagers or released criminals. In half of these cases, the rapist is a person with whom the victim is already familiar, even if they have only just met at the house of a mutual acquaintance or at a bus stop. In the case of teenage girls, who are not always able to say “no” to an adult, the statistics are even higher: four out of five victims of sexual crimes suffered at the hands of a neighbor, class-mate, or family friend. So how can you say woman’s right over her body is responsible for the increase in rape cases? Why not the son, the hormones, and alcohol?

I think this type of argument has a motivated intention to maintain masculine dominance over feminine rights.

Sangeeta Singh: “Woman’s right over her body” in the American context was about the right to have abortion. What is your implication of using this slogan in the Indian context?

S.S.: Let us discuss how the ‘body’ of a female acquired its place in the total Western discourse. In the nineteenth century, when the Contagious Diseases Act was enforced in Britain and women were forcibly examined for venereal disease, the ‘body’ also came into prominence. Josephine Butler was the prominent figure to raise her voice through the campaign. In feminist history, we find the Seneca Falls Convention (July 19-20, 1848) does not mention the body, it was first mentioned as a marker of race and class differences within the feminist movement by Sojourner Truth in her famous speech, “Ain't I a Woman?” at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851.

Truth told in her speech,

“I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear de lash a well! And ain't I a woman?”

However, credit goes to Simone De Beauvoir, who embodied the ‘female body’ with a philosophical strategy. In the first chapter of The Second Sex, Beauvoir reviews the data of biology and later she provides an account of the phenomenology of the body as lived throughout the different stages of a woman's life. Here she is explicitly offering her narrative as an account of lived experience, the body in situations and not as part of the data of biology. She discusses social issues primarily affecting women in our culture, such as birth control, abortion, the family, sexual discrimination and harassment, and rape. Though Beauvoir begins her book with women’s bodies, she later she states that ‘connoisseurs’ do not declare every human with a uterus as a woman. “It would appear then," she writes, “that every female human being is not necessarily a woman; to be so considered she must share in that mysterious and threatened reality known as femininity.” Beauvoir thus rejects the female body and from that time onward, feminist philosophy has been denying the need of a female body or female sexuality, and their only aim was in liberating women from reproductive tasks. Women were barred from beauty consciousness and from using cosmetics or fashionable dress and ‘femininity’ of a female was considered as the ‘negative’ aspects of her nature.

Luce Irigaray, a Belgian feminist, philosopher, linguist, psychoanalyst, sociologist and cultural theorist identified this ‘masculinism’ of feminists in her well-known book Speculum of the Other Woman (1974) (translated by G. C. Gill, and published by Cornell University Press, Ithaca). She pointed out that in the thoughts of these feminists, man was presented as the universal norm, and sexual difference was not recognized or recognised in such a way that woman was conceptualized as the ‘maternal-feminine,’ which had been left behind in the move to abstract thought.

I don’t know the actual facts and happenings with an infant girl-child, but in Asian and African countries, it's a regular practice to breastfeed girls for a shorter time than boys so that women can try to get pregnant again with a boy as soon as possible. In the case of adolescent girls, they are provided with less food than their brothers by their own mothers. As a result, girls miss out on life-giving nutrition during a crucial time in their development, which stunts their growth and weakens their resistance to disease. Sunita Kishor published a survey report in American Sociological Review (April 1993). In her article “May God Give Sons to All: Gender and Child Mortality in India,” she writes “despite the increased ability to command essential food and medical resources associated with development, female children [in India] do not improve their survival chances relative to male children with gains in development. Relatively high levels of agricultural development decrease the life chances of females while leaving males’ life chances unaffected; urbanization increases the life chances of males more than females. Clearly, gender-based discrimination in the allocation of resources persists and even increases, even when availability of resources is not a constraint.” Is this not gender discrimination as related to the body of a female?

Sangeeta Singh: How does your feminism differ from feminism in the West? Since you also talk about writing the body isn’t it the same as ecriture feminism of the French feminists?

S.S: For me, feminism is not a gender problem or any confrontational attack on male hegemony so it is quite different from that of Virginia Woolf or Judith Butler. I accept feminism as a total entity of female-hood, which is completely separate from the man’s world.

To me, femininity (rather than feminism) has a wonderful power. In our de-gendered times, a really feminine woman is a joy to behold and you can love and unleash your own unique yet universal femininity. We are here for gender sensitivity to proclaim the differences between men and woman with a kind of pretence that we are all the same. Too many women have been de-feminized by society. To be feminine is to know how to pay attention to detail and people; to have people skills; and to know how to connect to and work well with others. There will be particular times and situations within which you'll want to be more in touch and in tune with your femininity than others. Being able to choose is a great privilege and skill.

I think ‘femininity’ is the proper word to replace ‘feminism,’ because the latter has lost its significance and identity due to its extensive involvement with radical politics. Femininity comes from the original Latin word ‘femina’ which means ‘female’ or ‘women’ and certainly the word creates debatable identical characteristics. It separates the female mass from a masculine world with reference to gentleness, empathy, sensitivity, nurturance, deference, self-abasement, and succorance. And patriarchy also sets the group alien from them in their traditional milieu.

There are many more differences in theories among scientists, anthropologists, and psychologist regarding the nature and behavior of the female mass. Biologists believe the role of our hormones, particularly sex hormones, and the structure of our chromosomes are responsible for such a dichotomy in gender, though some queer theorists and other postmodernists, however, have rejected the sex (biology) / gender (culture) dichotomy as a “dangerous simplification.” Psychology, often influenced by patriarchy, categorizes women as different from the masculine world in certain behavioral, emotional and logical areas. Social anthropologists deny the concept of biology or psychology which keeps women aside from the masculine world. Simone De Beauvoir’s saying “one is not born a woman, but becomes one” impressed social anthropologists so much that they create a different theory of feminine socialization.

In my essays, I have constantly tried to analyze the ‘truth,’ as related by biologists and anthropologists. What I think true to my sense and sensibility, I have expressed without any hesitation.

Sangeeta Singh: Don’t you think ecriture feminism limits the writing style of women writers? Doesn’t’ it become prescriptive?

S.S.: I don’t consider myself as a conformist because I consider myself more a writer and as a writer, I think I am always a genderless entity. In my opinion, a writer should not have any gender. But still, patriarchal society has prevailed; is there any possibility to have a genderless society?

Sangeeta Singh: What would you like to say about doubly marginalized women like the tribal women, widows in ashrams, or women from lower castes and poor women who have to deal with the daily grind of survival and humiliation? They are deprived of the basic human rights. Do they have time to think about sexual liberation when other issues of survival are more important to them?

S.S: A Dalit or tribal woman not only struggles for her lower economic status, but she has to live with a high risk of gender-based violence. At the household level, incest, rape and domestic violence continue to hinder women’s development across India. Forty percent of all sexual abuse cases in India are incest, and 94% of the incest cases had a known member of the household as the perpetrator. Dowry related deaths, domestic violence, gang rape of lower caste women by upper caste men, and physical violence by the police towards tribal women all contribute to women’s insecurity in India. The class and caste structure inadvertently put poor women from lower class and tribal communities at the most risk of violence. Class and caste divisions also create grave challenges to poor, lower caste, and tribal women in accessing justice and retribution as victims and survivors of violence. So, sexual factors have a significant role in women’s life as their economic condition and so I argue for two types of liberation for women. One is economical and other is sexual.

Sangeeta Singh: How does a woman’s sexuality play a major role in the understanding of feminism in India?

S.S.: In marital life in India and many other countries around the world, a woman has no sexual rights. She cannot express her desires and even she is not supposed to enjoy sex as it is told in the Hindu code that a wife is needed only for giving birth to a ‘male child.’ Expressing her own desire for sex or talking freely about orgasm to even one’s own husband may also be termed as a chasteless and debasing activity for a woman.

Though the Women and Child Development Ministry (WCD) and the National Commission for Women (NCW) have advised the government to amend the 1973 Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and the 1872 Indian Evidence Act to recognize new categories of sexual assault by redefining rape to include sexual assault (including domestic sexual assault) of any form in its definition, still, most married woman are facing such marital rapes in their daily lives.

But talk about these ‘dicey’ topics by a woman is considered vulgar. Also, nobody thinks it proper to ask a woman before subjecting her to the killing of her fetus yet now, in some parts of India, ‘honor killings’ are granted if a woman steps out of bounds — by choosing her own husband, by flirting in public, or by seeking divorce from an abusive partner — she has brought dishonor to her family. Yet all these matters are related to a woman’s body and still, that woman has no right to make any of her own decisions.

In total, we can see the term ‘sex’ and ‘female sexuality’ has been totally misinterpreted in the discourse of Western feminism. Sexuality is not only a bodily matter and it does not limit itself to only sexual behavior and sexual activities, though they are a major factor. And most of the real meaning of female sexuality relatively termed with her body as well mind.

Sangeeta Singh: Does your writing represent only particular middle class women and their issues?

S.S: No, never. Many of my stories are related to the protagonists who come from urban or tribal background. Yash Publication of Delhi is going to publish a collection of my Hindi translated stories on these downtrodden ‘Dalit’ characters. One of my novels Pakshivas (this novel has been translated into Hindi and Bengali) is the saga of an untouchable, downtrodden cattle bone collector, Satnemi family from Kalahandi, the most backward region of western Orissa.

Sangeeta Singh: Do you think writings in ‘bhasha’ literatures in India are dependent on their translated versions to find a larger audience?

S.S.: Yes, as India is a country of vast linguistic diversity, translation of Indian Literature from one language to another has a significant role to capture the wide audience from all over the country. But if you think English is the only language which could pay this role model, then you are probably wrong. Once the Indian author Shashi Deshpande expressed her ideas that the English language is in some ways harmful to Indian culture not because it is the language of the ex-colonizers, but because it has become the language of the privileged, elite classes in India. She admits that when she writes in English she is aware that her work will reach out to only a few English-speaking readers, most of whom will be thinking the way she does. The problem is that if an author writes in English with the purpose of changing social traditions, the language excludes the poor and down-trodden whose involvement is most needed, and English has no place in the daily lives of those people.

But it is worth noting that English is the only source where a link can be made with global literary fields; although in India, the readability of literature in English shows a minuscule acceptance despite the rapid growth of literacy in English and in incomes of urban Indians. Presently and after globalization, it has remarkably placed its significance and never anyone today could define its tenure as colonial or outsider.

Sangeeta Singh: Do you think that a lot is lost in the process of translation of your work?

S.S.: Yes, many times I feel the translator can’t transform the feelings or emotions or facts I want to express. Maybe a translator will be successful in transferring the message, but how about the beauty of the language or the aesthetic. One language might be beautiful according to the native speaker, but if it is transferred into another language the beauty of language will not be the same. On the other hand, if the translator just focuses the beauty of the language, he ignores the message or the idea.

Sangeeta Singh: Do you think that feminism in the west has influenced feminist rising in India and other third world nations like Africa?

S. S.: Certainly westerns are premier in Feminism, but unlike Western countries, feminism in India had been motivated and ignited mostly by males and never females. It is a very interesting fact that in the colonial period, we find none of the female authors came forward with any question over the patriarchal milieu except some Anglo-Indian writers like Bithia Mary Crocker (1849-1920), Maud Diver (1867-1945), Sara Duncan (1861-1921), F. E. Penny, Alice Perrin (1867-1934), and Flora Annie Steel (1847-1929). They all are now forgotten, but once they played a major role in molding conflicts and collusions between British feminist discourses at the turn of the nineteenth century and contemporary conservative discourses bolstering colonial patriarchy. Though they were related to India somehow by their birth; culturally, they were not associated with India. The trend of feminism began in the late nineteenth century with the rise of the reformist movement in India by male reformists like Ram Mohan Ray, Chandra Vidyasagar, and others.

I can’t say more about development of Feminism in Africa as this field is yet to be studied by me.

Sangeeta Singh: Who are the feminist writers from the west who have influenced your writings? You have been compared with Judith Butler and Simon de Beauvoir from the west, but you contend that your feminist position is different from their feminism. Could you elaborate how?

S.S.: No doubt Simon de Beauvoir has inspired much to think more about feminism but not in my all writings. So far as the question related with literature or fiction, there are always male writers than female counterparts who impressed me.

Though Beauvoir has inspired me first to think over feminism, but I possess very different views from western feminist. I have opposed Simone De Beauvoir’s ‘other’ theory and opposite to her I believe that there are inherent physical, behavioral, emotional, and psychological differences between men and women and we affirm and celebrate these differences as wonderful and complementary. These differences do not evidence the superiority of one sex over the other but rather, serve to show that each sex is complemented and made stronger by the presence of the other. As a different unit, similar to man, the female mass has their right for equity as well. You can read more about my differences with Beauvoir on ‘other theory’ from an article titled ‘Other” at Wikipedia.

Now about Judith Butler. The concept of ‘right soul in a wrong body’ developed from Virginia Woolf′s novel Orlando - A Biography to which Judith Butler described those signs or analytical models which dramatize incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender and sexual desire and named it as ‘queer theory’. In my book Sensible Sensuality, I discussed these gestures and showed how these are throwing out powerful rhetoric of ‘thwarting the binary gender system’ means nothing if it comes from somebody who hates the world, loses his or her confidence to face life, and doesn't like himself or herself as a person. I can understand the positions of intersexuals or transsexuals who are born with differed biological bodies. There should be rational steps to make all feel comfortable and to mix up everyone into the mainstream. What I am against is the pop-culture clichés to express these feelings like “man trapped in a woman's body” or “woman trapped in a man's body.”

Sangeeta Singh: Feminism has branched out into many trajectories; can we talk of cross cultural feminism in the present scenario? Are there any cross connections? In the age of accelerated globalization, migration and displacement cross cultural feminist exchanges and dialogues become a basis for negotiating culturally differentiated feminist positions. Do you think third world feminist strategies can help feminist in the west and vice versa?

S.S: Recently in several European countries, a tendency to ban this full-body covering burqa or the face-covering ‘hijab’ has been seen and as governments there are trying to outlaw this dress code, which is pushing many countries toward a debate. In my blogging ‘Banning the Burqa: What’s Really Being Hid?’ I commented: “I think it is totally undemocratic to dictate any code of living to anyone. Democracy means freedom of choice! If anyone has freedom to wear jeans, they should also have the freedom to wear ‘burqa.’ Leave women to wear what they want.” What I find more a gender bias in this law is that this ban, in fact, would reduce the equality between men and women — whereas men are allowed to wear whatever they want, women again have their rights restrained. It is foolishness to think that by making any law or dress code, the institution making its rules can make people obey and follow as dictated. Rather, it usually serves to ignite emotions and increase the impulsive alienated attitude among some communities. But on the other hand I believe, if we have to support the Burqa wearing females, we should have to support Aliaa Magda Elmahdy’s attempt to publish her nude photos.

But it is also true that in the name of cross cultural feminism feminine mass has to bear a risk of becoming a tool in the hand of patriarchy control. For example: supporting Female Genital Mutilation in the name of cross cultural feminism seems to be harder for me. Holding a religious conviction and faith is a matter that must be left absolutely to each person’s inner choice of free will. It is a very sad commentary on mankind that they have over time turned all the teachings brought to them about Truth and Life into religions; and have maintained these religions with iron-clad rigid dogmas and doctrines. This way, the society, or particularly to say patriarchal society has brought serious dilution, and in some cases distortions, into the true teachings of the Prophets and Truth Bringers. Patriarchy always used religion as a tool for suppression to women and hence I think it is improper and harmful to add religious beliefs rather individual conviction to women’s moral values in the name of cross cultural feminism.

Sangeeta Singh: Some critics have criticized the feminist writings of the third world as tokenism and sometimes even farcical, what do you have to say to such kind of criticism?

S.S.: I don’t think feminist writings in India are farcical. Before criticizing feminist writings, we have to keep in mind that a literary writing should not be propagandist one. The tabloid issued for any political movement can’t be named as literature. So, while judging writings of Ismat Chugtai, Amrita Pritam or Kamala Das, we have not to fix a feminist norm rather we have to keep in mind that how much sincere they are to their feelings and experiences with their womanhoods.

Sangeeta Singh: If a feminist writer chooses to write about the patriarchal dominance in the Hindu or even in Muslim traditions she is indicted for having joined hands with the west by the fundamentalists. Have you also faced similar kind of censure when you wrote against the grain of the Hindu tradition?

S.S.: When my novel The Dark Abode first published in Odia under the title of Gambhiri Ghara in 2005, the Hindu fundamentalists raised their brows and I have to bear many insulting words in the name of criticism. One of our senior writers rebuked me over phone for playing with religious sentiments. But Gambhiri Ghara gained instant readers’ appreciation and good name in Odia literature and the book proved itself as a best seller of the time. Later it was translated and got published in English, Bengali, Hindi and Malayalam. In Bangladesh, the novel became popular and could attract critics’ attention.

Sangeeta Singh: You have used the Uma Shakti Myth in your novel The Dark Abode. Some scholars might blame you for promoting the Hindu religion and marginalizing women who don't follow Hinduism.

S.S: Religion and mythology are two different fixations. Religion is the broader term: besides mythological aspects, it includes aspects of ritual, morality, theology, and mystical experience. A given mythology is almost always associated with certain symbolic representation of ideas or philosophy of a ‘group’. It is very interesting to note that though Mesopotamian, Greek and Hindu civilizations, religions and cultures existed in different parts of the world and were separated by great distances and time, but there are some amazing similarities between their fables and myths. The concept of goddess always lies with sexuality and we find great similarities in all the myths of goddesses in worldwide. In Sumer, the goddess was known as Inanna, and in Babylon and Assyria, was known as Ishtar. She was Aphrodite for the Greeks. The Egyptians called her Hathor, Quaddesha and Aset. To the Phoenicians, she was Astarte. To the Hebrews, she was Ashtoreth and Ashera. And to the Philistines, she was Atergatis. So, the concept of Uma is universal idea/ philosophy of sexuality in all other cultures.

Sangeeta Singh: The foreword of the novel opens with metta, mudita, upekks” Pali words that mean love, joy, to see within; Are these words symbolic of the theme underlying your narrative?

S.S.: In Chapter 2 of TDA, Kuki told Safiq, “What is the point of living like a caterpillar, or leading a life of unbridled enjoyment of female flesh without any emotions or attachments? Do you think I have been attracted towards you in anticipation of physical pleasure? I wish I was aware of all this from the beginning.”

Here ‘Caterpillar ‘is a symbol of ‘sex hunger’ and Kuki wants to raise her from mire of sex to celestial expansion. You could mark that the total novel is the description of slow process how a perverted person who enjoyed 52 fair sexes could raise himself to a perfect self in love.

Sangeeta Singh: Why have you brought the “historical background” to the foreground towards the end of the novel , since the novel deals with “personal story” of Kuki and Safiq, History remains in the background throughout, then why a sudden reversal towards the end?

S.S.: The ‘historical background’ has not been brought at the end only. You could mark the starting of novel is from a ‘historical back ground’ where the partition, the Kashmir problem and Indo-Pak relations ship or Hindu-Muslim hatred scenarios in Kuki’s nostalgia occupy a major portion.

The novel also delves into the relationship between the ‘state’ and the ‘individual’ and comes to the conclusion that ‘the state’ represents the moods and wishes of a ruler and hence, ‘the state’ actually becomes a form of ‘an individual’. So, the ‘personal story’ of Kuki and Safiq actually represents the story of a subcontinent.

Reviewing TDA, Bangladeshi eminent writer Selina Hossain writes,” The course of life of two different citizens of two States does not give any other solution than waiting. How the State obstructs and suppresses the individual freedom has been shown in the version of Safiq, the painter. When he writes letter to Kuki in pseudonym, she understands that ‘It is a ploy to hide his identity from the Military Junta.’

Kuki wrote to Safiq, ‘Don’t think that there is any less exercise to cook up history in our India. Here the history changes its narrative with the change of rulers. It becomes difficult to ascertain who is the hero, who the villain. The historical facts read by the father are changed when it is the turn of the son to read it. Can you tell when the history of man will be available to man written impartiality?’ The writer does not rest without telling the tale of the individuals, the State, political tit bits, the behaviour of the military and misrule of the State in her novel. The inner conflict gives the heroine much trouble. Different aspects of the crisis of a woman’s life have been described in this novel. The woman fights with herself.”[ See: (The Review of the Book is in Bengali, published in Shamokal a Bengali daily of Bangladesh and reviewed by Ms. Selina Hossain (saquib@agni.com), the famous writer of Bangladesh and translated by Aju Mukhopadhyay, (ajum24@yahoo.co.in ,ajum24@gmail.com) who lives in Pondichery, India).

Sangeeta Singh: Macro level of politics has been mentioned only fleetingly in the last chapters, you have tried to include all forces that regulate the destiny of a personal relation be it tradition, macro level politics, economic forces, political and geographical wars, religious and ethnical non tolerance and even terrorism. Was your intention to highlight the forces against which all human beings are pitted?

S.S.: Your observations are very correct. That is why Kuki could realize Virginia Woolf’s sayings: “As a woman, I have no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world.”

Sangeeta Singh: The character of Safique has been left in shrouds of mystery in the end. Is it deliberate? How do you account for it?

S.S.: I am sometimes doubtful if all the imaginary situations I have used in my fictions are mine. Sometimes the imaginary is "running by itself" and the content is not typically what I would imagine out of my own desires. I suspect something mystic with writings can be real. To suppress such communication is something I am unsure of, because the characters of my fictions want to live their lives by their own will, because they want to heal their wounds, and how can I deny such a positive force? Perhaps it is the ‘Safique’s will’ which would make him imperceptible at the end.

Sangeeta Singh: What is the relevance of the collage presentation of the rather erotic sketches by Ed Baker in the novel? Do they convey something you could not write as explicitly as a woman writer? How do you connect the sketches with the narrative?

S.S.: I think mine is the expression of female sexuality in fiction or text form and Baker tries to represent the same idea through art form. In my original Odia (Oriya) novel there are also similar sketches drawn by Dr. Dinanath Pathi, the Secretary General of LalitKala Akademi.

Sangeeta Singh: Thank you for sharing your insights about feminism in the Indian context. Wish you good luck for your future projects.

27-Feb-2013

More by : Sangeeta Singh

|

Insightful, courageous and compassionate perspective! Thanks. |

|

Very insightful...the writer goes to the heart of the matter to clarify the issues under discussion.A good read! |