Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

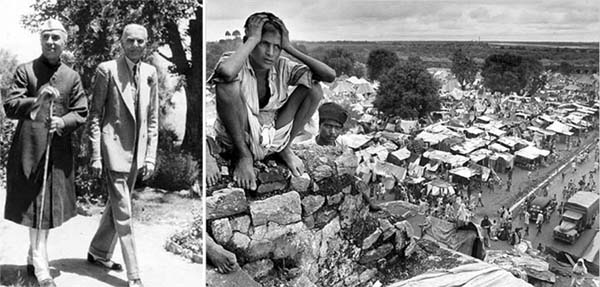

The word partition evokes an emotion the range and depth of which far exceeds the clamor and tears of the ground it vivisects into two or more than two. It is not only the relationship between the two parts coming to terms with a newness that bears the brunt but also the present and future run the risk of falling into the habit of hiding behind the big wall of partition. When we sit under the shadow of that wall the ground seems trampled by either malodor of obduracy or effeteness of submission. And we never forget the wall, the partition.

Jaswant Singh’s book seeks to revive once again the ever mootable question of who divided India. Jaswant, now expelled from BJP sought to turn the existing notion of ‘Jinnah being the conceiver of two nation theory’ on its head by suggesting that Jinnah did not win partition but Nehru and Patel conceded partition to Jinnah with British always present as ever helpful midwife. Historians bear out Jaswant’s political iconoclasm and state that his book divulges nothing lurid and radical. The argument goes it was not Jinnah who demanded Pakistan but haste of Nehru and Patel to jump to supreme power that led them to agree with Mountbatten’s crude ‘surgical solution’. But if the answers were as simple as Jaswant would have us believe and as clear and pellucid as historians especially on other side of the border pretend to know the furor that Jaswant’s book has met with would largely have been absent.

Unfortunately once again the crystal clean answers will elude us but still we can have a picture as to what occasioned the division that engendered a bloodfest of centuries and exodus never seen before. Three primary protagonists Nehru, Jinnah and Mountbatten have their roles well defined in the history text books of India and Pakistan. In India, it is Jinnah and in Pakistan it is Hindu extremists Congress headed by Nehru that caused partition. Every nation needs heroes. At the time of independence India had plenty of them in Gandhi, Nehru, Abul Kalam Azad, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, Rajaji and many more. Newly created state of Pakistan had only one and perhaps the best till date. The one who had helped Pakistan come into being, whose shrewd arguments and astute reading of Muslim paranoia, however slight it was, had altered the map. For millions of Muslims it was nothing short of an epiphany: an independent sovereign state of their own to be ruled by their own people. No longer did they run the risk of marginalized by a Hindu majority as Muslim League told them. M A Jinnah was now Quid-E-Azam (great leader).

Here is contradiction. If Jinnah had won Pakistan for Muslims how come he was not directly responsible for partition? Why Nehru and Patel are being defamed? The general defense is that Jinnah never demanded a territorial Pakistan. All that he was trying to ensure was a greater autonomy for individual provinces as to endow provinces with Muslims majority with enough power in their hands independent of clutches of majoritism. Nehru and Patel did not relent and hence a new state was carved out of India.

But if that is a case then how come he still was a nationalist? Jinnah himself had relegated himself from being a nationalist to a leader of only Muslims. He held that Nehru was representing Hindus and he Muslims, a quasi truth preposition, right in his case and wrong in Nehru’s. Pakistani-American historian Ayesha Jalal, Mary Richardson professor of history at Tufts University USA and the writer of “The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the demand of Pakistan” argues that once the all India negotiations failed to make headway and the Hindu Mahasabha had called for the division of two main Muslim majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal in early 1947 Nehru and Patel insisted on partition; the sole spokesman of India’s Muslims tried to avoid such a catastrophe till the very end.” If Jinnah was the sole spokesman of Muslims (one religious community though with substantial population) then ipso facto Jinnah ceases to be a nationalist. Regardless of the credentials of the historian one needs to be utterly credulous to not take the statement “Nehru and Patel insisted on partition” with a pinch of salt. What could have been and was in all probabilities a tragic nod can’t be made to wear the colors of an importuned insistence as Ayesha Jalal seems to be doing. Even if we assume this outlandish preposition that Nehru and Patel insisted on partition rather than trying to accommodate Jinnah’s concerns for Muslim minority then what Jinnah is suggesting at when in a speech at the Muslim League convention in 1940 he says, “very often, the hero of Hindu is a foe of the Muslims. To yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority, must lead to rowing discontent and the final destruction of any fabric that may be built up for the government of such a state.” Doesn’t this statement corroborate what we all associate Jinnah with?

If we go by some statements of the person who once wished to be a Muslim Gokhle and wore an anglicized liberal secular persona till his death before and after that famous august 11, 1947 speech delivered before the constituent assembly of Pakistan in which he said, “you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques, your caste creed and religion has nothing to do with business of the state” then it becomes clear that either secular and liberal Jinnah had killed himself and given birth to a new Jinnah in pursuit of his political aims and had reconciled with the bitterness of being in cohorts with communal Muslim League propounding communal and sectarian beliefs or more than any idea of India that Jinnah may have had it was his jealousy for Nehru that got better of him. Jinnah was not immune from the bug of inconsistencies.

If in 1947 he wanted Pakistan to be a secular state but just two years after while addressing the Karachi bar association on January 25, 1948 he opined that people who were rejecting the idea of an Islamic state were indulging in mischief and stressed that constitution of Pakistan would be based on Sharia. Three years ago in November 1945, he had written to the Pir sahib of Manki Sharif in NWFP that the constitute assembly of Pakistan would be able to enact laws for Muslims which won’t be inconsistent with the Sharia laws and Muslims will no longer be obliged to abide by un-Islamic laws. These statements illustrating the communal politics played by a ‘secular’ Jinnah don’t end here. There are more statements recorded in the form of his speeches and letters that allude to Jinnah’s not having any qualms in playing out communal politics and donning an inflexible approach to his views cleverly weaved around the spindle of Muslim’s interests.

Quite oddly though it may seem but Jinnah did not represent all Muslims of India contrary to what he claimed. According to a population survey conducted as recently after partition as 1951 India was house to more Muslims than was newly Islamic state of Pakistan. This evinces a majority of Muslims had discarded the theory of Muslim interests in jeopardy at the hands of Hindu majority propagated by Jinnah. These Muslims decided to stay back in the India of their birth even at the risk of being minority when they had the choice to be part of majority in a separate Muslim nation. Despite odds these Muslims today are helping their India as much as any member from majority Hindu community can.

So what conclusions do we draw? Which Jinnah do we deem real? One who envisages a modern secular state of Pakistan or the one for whom Pakistan can only be an Islamic state? Don’t Jinnah’s flip flops compel us to ask some insouciant questions? How did a person who was never open to the lure of any office fall prey to his political ambitions? Did a demeanoral human peccadillo of egotism and vanity compel him to be adamantine even at the expanse of his own true self, doused in secular waters, a self that he lived with for most part of his life? No one can repudiate the fact that Jinnah who seriously contemplated the thought of settling down in London till 1930 and did spend few years there even when independence movement in India was at its peak, had ceased to be a secular person in at least the last 10 years of his life however much historians on both sides of the border claim otherwise. Every aspect of his politics in these years was imbued with communalism.

Jinnah was a liberal, dapper, westernized personality, seldom praying, often ridiculing Muslims for not being parsimonious enough, embodying all the virtues of a sedulous and honest man. He was an extremely competent lawyer and took pride in seeing himself as the bridge between the two main communities of Hindus and Muslims, even after joining Muslim League. Gopal Krishan Gokhle once called him ambassador of Hindu Muslim unity. On flip side Jinnah was fastidious and attention demanding personality. He wanted to be hub. The only man Jinnah could draw parallels in Congress was Nehru, a man he could never get along. It was the presence of Nehru in congress that drove Jinnah out. The joining of Muslim League, a communal outfit Jinnah could never have found anything in common with was just a support Jinnah needed to lean on. This was a marriage that suited both. Muslim League had in Jinnah a man of high intellect and great spunk in their fold. However absurd as this may seem it was not as much the clash of communities that led to partition as the clash of personalities. The imperious voice of Jinnah mouthing communal concerns never found consonance with not only steadfastness of Nehru and Congress but also with interests of a united India.

Today in India everyone seems to have grown bored with the deifying of Nehru and Gandhi so it is quite a fashion to revile these two personalities whom India owes a lot. Nehru can be lambasted for partition as most historians on both sides of the border are doing with a new found enthusiasm sourced from a right wing politician’s book for not being pliable enough to the British cabinet mission plan in 1946 which Jinnah agreed to. According to this plan the federal government would have had control of some key areas in governance like foreign, defense, home and rest would have gone to states. The ‘nationalist’ Jinnah would have at least six Muslim governed provinces over which federal government would have had near zero control. That would have been going way beyond article 370 including the right to form sub national collectives, constitutional statuaries or even secede. We don’t need a prize to guess what India would have been like with in 10 years of independence if Nehru had acquiesced to such a demand. To add insult to the injury who would have stopped under such a system of governance some 600 odd princedoms from not demanding even greater autonomy in their internal jurisdictions. If Nehru would have done what today’s historians often accuse him of not doing to avoid partition then perhaps we would have been confronting not one Pakistan today but several, all around us. Independent India has survived many insurgencies in the various part of India thanks to Nehru’s cleaving to an India with centralized control of power. The balkanization which Nehru feared would have been the only reality, otherwise.

Everyone who finds fault with Nehru’s stubborn attitude in the events building up to partition has to have problems in reckoning India as one sovereign nation. There have been many people for whom India has always been a multination entity rather than one country. In a way these people are not far from reality in so far as what India was before British began to consolidate their grip on India. Nehru himself was a bit skeptical of the degree and depth of national consciousness ‘that brings the sense of belonging together’ in colonized India but was assured that a nation without this national consciousness can’t survive longer. His emphasis on centralized control was a step forward in that direction to endow as diverse a nation as India with that utter important sense of belonging together.

Prophecies were always galore that it is but natural for this country to get dismembered. 62 years after independence India has falsified almost every such doom theory and Pakistan a symbol of Jinnah’s ‘Muslim governed province’ though in the form of a complete separate nation but enjoying the parity of religion is still struggling to find its feet on the ground of stability. Today we see what Nehru envisaged flourishing and what Jinnah stood for in tatters. Yes, partition could have been avoided if Jinnah had acted more like a nationalist than a community leader. Yes, one partition could have been averted were it not for Nehru holding his own against Jinnah’s demands for a loose federation but in that case for how long and how many.

30-Aug-2009

More by : Pramod Khilery