Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

While the first true stupas were constructed after the reign of Ashoka, still there have been many monuments to Buddhism erected during his rule. Some prominent ones were stone or cast iron pillars (stambhas) which, though architecturally insignificant, play an important role in terms of their symbolism, standing as mid-points between the drawing of a mandala on the ground, and a full-fledged stupa. They also represent a three-pronged approach: the non-existent space within the stone pillar itself, the annular space between the pillar and its railing, and finally the world outside the railing – this triad became one of the key features of the stupa itself.

While the majority of stupas in India consist of a solid hemisphere surrounded by a railing, other stupas such as the great stupa at Borobodur (built a thousand years after the one at Sanchi) are considerably more complex. As opposed to the Sanchi stupa, the one at Borobodur consists of a polygonal base, with steps leading up to the summit and punctuated by as many as 72 smaller stupas along the way.

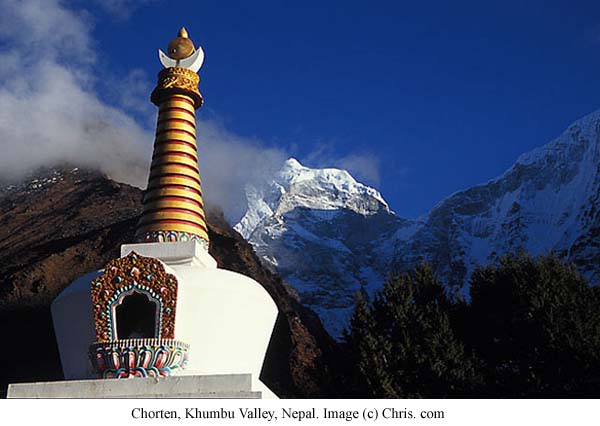

The chorten in Tibet

After being introduced into Tibet, the Indian stupa underwent inevitable changes in its form and nomenclature. Its form changed, especially with regards to the anda or dome at its summit. While the Indian stupa is a circular dome, the Tibetan chorten is more elliptical, like an oval above a rectangular base. We also find at the summit a series of ring shaped enclosing ‘umbrellas’, topped by a disc. Though this change in form from the Indian stupa is co-terminous with the transformation of the religion itself as it moved northward to Tibet, in no way does the chorten lose any of its powerful imagery and symbolism as the seat of Llama-centered Buddhism.

As opposed to the central Indian stupa, the Tibetan chorten is a fairly complicated form, with 8 or more different ‘models’ being described, perhaps corresponding to the 8 major stages in the life of the Buddha. However, the most common model by far is the one that describes Buddha’s ‘supreme enlightenment’, consisting of a square base with steps above it, which is then topped by the dome – which is really an inverted oval called the bumpa. Above the bumpa rises a spire with the characteristic ‘umbrella’ shaped rings, which is then finally crowned by a ring and a crescent ‘moon’. Apart from this model, there are also examples corresponding to the ‘descent from heaven’, and the ‘many gates’ tradition of Llama Buddhism. This last is the most monumental of the many chorten found in Tibet, of which one example is found at the monastery at Gyantse.

Fine examples of chorten are found in Khumbu in Tibet, most of which are based on the traditional stupas at Bodhnath. However, a distinctive difference is the one at the monastery at Tengpoche, which is clearly of Tibetan standards. Once again, this one symbolizes the ‘great enlightenment, and consists of a plinth or base above which are steps in the form of cornices rising up to the dome. In the manner usual with chorten of this type, the dome is an inverted cone on the sides of which are two large images of the Buddha. A drum above the dome is topped with thirteen ‘umbrellas’ which are in turn topped by an inverted crescent and a disc symbolizing air and the ether.

Gateways

Another form of architecture found in Tibet, and most particularly in the village and bazaar of Namche, is the free-standing gateway. While the origin is most likely Tibetan, some similarity is to be found with the gateways of the Sanchi stupa and other stupas in India in that there are mandalas and images of deities to be found on the underside of the lintel of the gateway. Other examples of similar gateways are to be found in Nepal, for example, at Tsarang. However, in Nepal, the gateways are of a much simpler typology, for example the one at the monastery of Garphu.

Monasteries or Gompas

A singularly large number of monasteries in Nepal, especially in the valley of Khumbu, are influenced by Tibetan architecture. In Tibet, the earliest monasteries date from about the 8th century AD, being patterned very early on in the form of strongholds or fortresses for defense. Apart from this secular role, the monasteries were also centers of learning, with immense work being undertaken in terms of translation of the Buddhist canons, which then enabled the spread of Buddhism as far afield as China under the Mongols in the 13th century.

This being said, it is true that Tibetan gompas or monasteries do not differ greatly in terms of shape and form, being generally two-storied structures, though a third storey is also to be found with less frequency. The ground plan, for one, is loosely patterned on a mandala, with the superstructure corresponding to the metaphysical and spiritual dimensions of this diagram. It is not uncommon to have a space dedicated to prayer-wheels before the main entrance to the gompa. In form the monastery consists of a central hall, from which other spaces radiate. For example, an atrium or porch is sometimes added to the entrance. A forecourt, surrounded by a portico – the yab-rin – is built on to the larger monasteries. The real hub around which the monastery revolves, or the place with the maximum religious significance, is the main hall discussed earlier – or the lha-khang. At Tengpoche and elsewhere, the lha-khang is in the shape of a square and corresponds directly with the mandala. One would imagine that the main deity, in keeping with the shape of the mandala, would occupy the centre of the hall, but in practice this occupies the wall opposite the main entrance. Further airiness is given to the structure by the presence of lofty beams and so called ‘shelf-capitals’ – spaces above the main pillars which support the structural beams of the hall.

Articulated against the forecourt or the cham-ra, whose function is mainly that of holding religious ceremonies, the whole monastic complex gives an impression of solidity on the outside and airiness on the inside, perhaps in keeping with Buddhist metaphysical concepts of the inner soul and the gross physical body.

These two aspects of Buddhist architecture in Tibet and Nepal – the chorten and the gompa – or the stupa and the monastery – highlight a vivid symbolism that seems to be the hallmark of all Buddhist architecture, and the function of the architecture, to come full circle – is to give a three dimensional aspect to the highly symbolic and metaphysical aspects of Llama Buddhism as it is – or was – practiced in Tibet and Nepal. Nothing could be further from the solid, interiorized forms of the chaitya and stupa as they are found in India, and yet upon deeper analysis, one finds tenuous links that have survived the obstacles of time, space and distance between these two different – and yet similar – interpretations in three-dimensional form of the ethereal philosophical concepts of Buddhism’s teachings.

17-Nov-2013

More by : Ashish Nangia