Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

No one can say when that freak cell got embedded in the deep recesses of Sudha’s brain. It could have been in her early childhood or teens or even later. But once embedded there, conveniently placed in the vicinity of her right cerebellum, that cell began to grow and multiply. Slowly, stealthily, steadily.

No one can say when that freak cell got embedded in the deep recesses of Sudha’s brain. It could have been in her early childhood or teens or even later. But once embedded there, conveniently placed in the vicinity of her right cerebellum, that cell began to grow and multiply. Slowly, stealthily, steadily.

For a freak cell it was indeed slow growing because it did not give her any problem when she herself was growing up. In her teens she was very active and in her youth she was in the best of health. There was nothing in the way she walked or talked or worked to indicate that she was carrying within her head a vicious tumor that in later years was to become so large as to cause a serious threat to her life and, subsequently, alter her entire way of living.

The first symptoms, misleading as they were, came in 1979, eleven years after our marriage and nearly a year after our eight-year old son underwent a heart operation. Kiran’s congenital heart condition was a constant source of worry for Sudha and me and it was a stroke of good luck that it was possible for us to get it surgically corrected in one of the best children’s cardiac centers in the world, the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children at Sydney, Australia. Dr Tim Cartmill, world renowned thoracic surgeon, performed the complex surgery in October 1978 in what was later described as ‘total correction’ of Kiran’s defect, Tetralogy of Fallot.

Kiran’s successful surgery gave us relief from the nagging tension that had been gripping us ever since his birth. But the happiness we felt was short lived as within about a year we became aware of the serious problem that Sudha herself was facing.

One day in 1979 Sudha told me, casually, that she was feeling some uneasiness a little above the left knee. She could not distinguish whether it was pain or spasm or sprain. Just some uneasiness a little above the left knee. There was no inflammation or any other visible sign of her condition. I suggested meeting a doctor, but she dismissed it, saying the discomfort would go after some time.

It did not. Gradually she began to feel more of it, still unable to characterize it. So in the second week of her complaint we met a physician, Dr Kochunarayanan. The doctor prescribed some pain relievers and vitamin tablets, neurobion, and asked us to meet him after a fortnight.

By that time we realized that there indeed was something wrong with her, though we could not say what. Neither could the physician enlighten us as to what was wrong. During the next few fortnightly visits to the doctor, the tablets kept changing but there was no letup in the discomfort.

Gradually her ailment appeared to give out more tell-tale, or rather ominous, symptoms. While walking she would suddenly lose her gait and would be forced to take a few fast steps before regaining her balance. That is, walking slowly she would abruptly speed up for a few seconds, involuntarily, and come back to the normal pace. She could not say what made her do that.

And then the alarm bell rang one evening. It was a Saturday and as was our almost unchanging practice, we had gone for a movie (as it turned out, our last movie together). My young son’s favourite music group at that time was ABBA and the movie house was showing a film on their Australian tour, ABBA The Movie.By the time we were inside the theatre, lights had dimmed. Holding Kiran’s hand and carrying little Parvathy I was walking ahead, with Sudha trailing me. As she was going up the aisle, suddenly she lost her balance and fell backwards. I heard the cries of some people sitting nearby and looked back, aghast, to see Sudha,in a sort of slow motion, falling backwards. Fortunately for us she did not fall on the floor, for a man who was walking behind her extended his hand to give her support.

Sudha was not that lucky a fortnight hence. She was climbing the stairs to our first floor room when she lost her balance again and fell back, to the landing several steps below. Hearing the thud and her muffled moans, all of us at home ran to the stairway only to find her in a crumpled heap, shell shocked and unable to move.

Fearing the worst, we carried her to her room and gave her some water to drink. A doctor living nearby, a relative came soon to examine her. It was our good fortune that in spite of the vicious fall there was no fracture or any other serious damage, though there were concussions all over. It did take quite some days to fully recover from the fall.

It was Dr Venugopalan Nair, an orthopedic surgeon we consulted after the fall, who suggested to us, for the first time, that what she had was a neurological problem. He referred her to a neurologist, Dr. Vasudeva Iyer, Professor of Neurology in the Thiruvananthapuram Medical College.

Dr. Iyer, an extremely nice mannered doctor, had the reputation for correct diagnosis. Unfortunately for us, in Sudha’s case he faulted on the diagnosis with the result that we wasted more than a year by pursuing a course of treatment that never helped to alleviate the problem that, instead, grew by leaps and bounds.

So for the next one year and more the doctor treated her, frequently changing medicines, ultimately asking us for weekly visits to a nearby hospital to get intravenous injections of a powerful drug. All the while her imbalance worsened, to such a level as to make her afraid of walking.

And the weekly visits to the hospital became a great ordeal, as she was unable to take even a single step without someone holding her. If she took one step forward unaided she was sure to lose her balance and fall down.

Dr. Iyer realized that there was no point in continuing with this line of treatment. But he told us so only when I asked him how long it could continue without giving any relief.

His diagnosis had been that there was a compression in the neck, the cause of which could be ascertained only through painful tests like mylogram. He wanted to avoid such tests for Sudha as far as possible. Hence the tablets and the injections.

One day when we were discussing her condition and he again propped up the compression theory, I asked him whether there could be any problem with the brain. He brushed aside my fears and said there was some compression in the region of the neck and that there was no problem above that point.

Perhaps reading my mind, he said if I wanted I could take her to another neurologist for a second opinion. I grabbed at the idea and he said he could give referral letters to any doctor in Chennai, Bombay or New Delhi. I suggested Chennai and he promptly gave me a letter addressed to the renowned neurosurgeon Dr B Ramamurthy, a father figure among neurosurgeons in the country.

Without losing much time, I fixed up an appointment with Dr. Ramamurthy, arranged accommodation in a hotel for a few days and made train reservations. We planned a brief program, hoping to return within a week with a prescription from Dr. Ramamurthy and, time permitting, having a pleasant sightseeing trip to Chennai city which Sudha was visiting for the first time. We even remembered to take our camera along, never realizing that the one-week trip that we planned would turn out to be a traumatic two-month ordeal for Sudha and that the trip would drastically change the course of our entire life.

~*~

It was with much enthusiasm that we embarked on our journey to Chennai on February 23, 1980. This was the first train journey for Sudha after our trip back to Thiruvananthapuram from Bangalore, on my transfer, five years earlier. Though getting into the compartment was difficult and painful for Sudha, the journey itself was pleasant. She chatted with a family that shared our compartment. We also discussed the things to buy in Chennai, the places to visit and the people to meet. Though meeting Dr. Ramamurthy was the main purpose of our Chennai visit, we were so fascinated by the journey that in the animated discussion in the train our medical mission received the least priority.

The following morning we went for a limited sightseeing, Sudha mostly remaining in the taxi. At Moore Market, however, she came out to get into some nearby shops and buy something or the other for the kids.

At 3.30 in the afternoon we reached Dr. Ramamurthy’s clinic. As was the practice there, his son Dr. Ravi, himself a neurosurgeon, did the preliminary examination of the patients. He made a thorough examination, asked Sudha many questions, made a detailed note and then ushered us into the room of Dr. Ramamurthy.

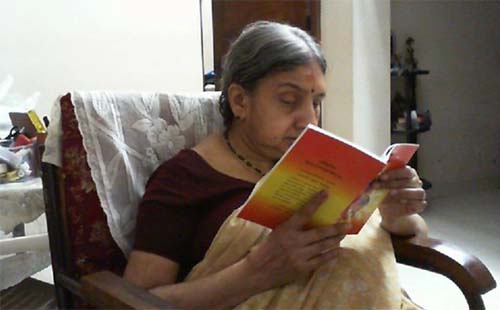

Sudha two decades after the operation

Sudha two decades after the operation

Though he was a world renowned surgeon who pioneered neurosurgery in India, Dr. Ramamurthy’s consultation room was rather spartan. To make up for that was his affable personality that made a meeting with him an unforgettable experience. He was genial, considerate, and he went out of the way to put his patients at ease. He did not ask anything about the problem my wife had. He only did some small talk, pleasantly asking Sudha about her family, about the journey and about her plans for the next day, all the while reading Dr. Ravi’s notes.

Dr. Ramamurthy took just one minute to arrive at his diagnosis. He looked into her eyes with the ophthalmoscope and seemed to know what was wrong. He did not tell me anything about it then. Just asked me to take her to a nearby X-ray unit on Mowbray’s Road and come back. Obviously, to confirm his finding.

As I was holding Sudha’s hand and taking her out of the room, Dr. Ramamurthy told me not to bother her by bringing her again to the clinic. ‘You seat her in the waiting room and come here with the X-ray,’ he said.

I did not understand the full import of what he said till I returned with Sudha after taking the X-ray. I was opening the half-door and ushering in Sudha when he told me, with no trace of his obvious annoyance, ‘I asked you to come alone.’ I realized then there was some serious problem.

I led Sudha to a settee on the corridor and rushed back into the room, my heart pounding. But what Dr. Ramamurthy told me then was something beyond my wildest fears. For, speaking in a subdued tone, often with aid of drawings scribbled on a piece of paper, he told me that Sudha had a Brain Tumor.

It was, he said, a Posterior Fossa Tumor, meaning the tumor occupied the back portion of the brain. As the Tumor obstructed the flow of Cerebro-Spinal Fluid (CSF) there was a buildup of pressure inside the skull. As this intra-cranial pressure mounts, there will be a telling effect on the optic disk. This condition, known as Papilledema, may lead to blurred vision, blindness and ultimately death. Sudha had Acute Bilateral Papilledema and needed an emergency surgery to relieve the pressure inside the skull. And, a major surgery, after a week or so, for the removal of the tumor.

I listened in stunned silence, unable to say anything. Praying to all Gods to see that this doctor’s diagnosis is wrong, I finally mustered enough strength to ask him how much time I would get to make arrangements for the surgery. No time at all, he said. ‘If I were in your position, I would admit her today and do the operation tomorrow.’

He told me that the operation could be carried out either at the Voluntary Health Services (VHS) Hospital or at the Vijaya Hospital, the two hospitals where he was consultant.

I told the doctor I would speak to my family and get back to him the next day.

I do not know how I faced Sudha waiting for me in the corridor. I did not have the courage to tell her what the doctor had just told me. Stifling my emotions and presenting a casual look, I just told her the doctor had suggested some more tests.

Back in the hotel I made Sudha lie down to rest awhile and then rushed down to the Reception to make a phone call first to Dr. Vasudeva Iyer. And he did not believe in the diagnosis of Dr. Ramamurthy. ‘On what basis did Dr. Ramamurthy say so. I think he is wrong.’

I told him he and my longtime friend Dr. Vijayaraghavan, Cardiologist, should discuss this matter and come to a decision on the next course I should take. Should I go ahead with the operation as suggested by Dr Ramamurthy or do anything else?

I then called Sudha’s father and cautiously explained to him the developments. I asked him to talk to Dr. Iyer and Dr. Vijayaraghavan to decide on what should be done.

Dr. Iyer called me the same night and said there should be second opinion as he did not think that Dr. Ramamurthy’s diagnosis was correct. He suggested that I take Sudha to the Christian Medical College Hospital at Vellore and consult either the head neurosurgeon Dr. Jacob Abraham or the second in command Dr. K V Mathai.

I did as I was told and that, I feel in retrospect, was the greatest mistake I had ever committed in my life: Accepting the erratic advice of a doctor whose year-long treatment had failed to provide any relief whatsoever and ignoring the sound, well thought out diagnosis of the greatest neuro-surgeon in India, one who was acknowledged as the Father of Neuro-surgery in the country. Perhaps Sudha would have led a normal, healthy life now had she been operated upon by Dr. Ramamurthy.

In retrospect again, that trip to Vellore should never have taken place. Vellore in fact opened up the flood-gates of misery for Sudha from which even now, three decades after that operation, she could not come out. I cannot blame Fate for that skewed operation in the Vellore Hospital that gave Sudha life-long problem of imbalance. She is continuing to pay a heavy price for my mistake.

Before leaving Chennai, I went to Dr. Ramamurthy’s clinic to inform him of the decision to go to Vellore as advised by the treating physician. Neither Dr. Ramamurthy nor Dr. Ravi was there. So I went to the counter, paid the consultation fee which was not paid earlier and left a note for Dr. Ramamurthy. He was so kind as to reply to that note. In a letter sent to my home address he thanked me for the consultation fee and said : ‘I am glad that you are taking the suggested course. My Best Wishes.’

~*~

Vellore Hospital staff informed me, when contacted, that Dr. Jacob Abraham was out of station. So I fixed up an appointment with Dr. Mathai. We left Chennai the same day by Brindavan Express, reaching Katpadi by 7.30 PM. The hospital was about four km from the Katpadi station.

After taking up lodging at a hotel opposite CMCH and leaving Sudha there, I went to the neurosurgery department for enquiries and later in the night spoke to Dr. Mathai and fixed up admission the next day.

At about noon on February 27, 1980 Sudha was admitted to the neuro ward, pending allotment of a private room. Panic gripped her the moment she entered the ward. Seeing many women patients in the ward with their heads shaved or in turban like bandages, she asked me a thousand times, in utter despair and great panic, whether she too would have to lose her hair and undergo brain operation like them. I vainly tried to console her saying God will be merciful and that with many tests yet to be conducted there was still hope for us. But she was far from convinced.

The almost hysterical questions and the tearful mutterings of self-pity continued for a day even as various tests were conducted and intense medication started. They lasted till a lady barber came in the evening to cut away her hair and clean shave her head. A great change had by then come upon her. For her it meant everything was lost. All her intense prayers had not come to her aid to ward off what was inevitable.

Sudha remained in absolute silence when the lady barber was doing her work. Except that there was a copious flow of tears that wet her hospital uniform. The lady barber noticed it and told me in a hushed tone: ’Madam is weeping.’ But I couldn’t hold back my tears either.

Sitting there, silently subjecting herself to such mundane preliminaries for major surgical interventions into her brain, which would have far reaching consequences on her life, Sudha looked as if she had resigned herself to Fate. What was remarkable about the silence was that she remained so during the next two months in the hospital, never uttering a word unless the doctor or the nurse or other staff asked her something. It was as if Hope had deserted her. The only occasion she smiled and seemed to be happy was when sprightly Reny, a ten-year old girl who underwent brain tumor operation and was now convalescing, came to visit her.

Sudha’s shunt operation, performed on March 5 to lower the pressure in the brain, was uneventful. The surgeon drilled two holes in the skull, inserted a shunt behind her right ear and arranged flow of the accumulated CSF through it to drain to the stomach. The operation started at 8.15 in the morning was over in two hours. She was brought back to her room in the evening.

It was about a week later, on March 13, that the major operation for the removal of the tumor was performed. Before that they had carried out an isotope scanning of the brain which gave them an indication of the position and extent of the tumor. The preliminary finding of the doctors was that what Sudha had was an acoustic neuroma which, fortunately, was a benign tumor.

Soon after the operation I realized to my horror that whatever be the other beneficial outcome of the procedure, it would definitely give her life-long imbalance. The surgical notes prepared by theatre staff are normally not seen by outsiders. But I chanced to read the note and take down some points when the file was kept on a table for some time by the nursing staff before it was taken away. What stunned me was the sentence ‘left half of the cerebellum was excised to reach the tumor.’ The cerebellum on either side of the base of the brain controlled our limb movements. If one half of that organ was removed, it would mean there would be deficiency in the movement of limbs on one side.

When Sudha was brought back to the intensive ward I noticed that her bandage was on the back of the head. I had read in the surgical note that the approach had been midline sub-occipital which in common parlance meant that the skull was opened at the back.

As I had seen some other patients with acoustic neuroma having bandages on one side of the head, behind the ear, I asked a junior surgeon in Dr. Mathai’s team, Dr Satish Kumar, whether it would have been possible to reach the tumor without removing the cerebellum if a lateral approach was taken. He looked at me in disbelief, as though I had said something outrageous, and dismissed my question with a wave of hand, muttering ‘What do you mean? No No No.’

But the loss of the left cerebellum was something I could not forget. I knew that whatever be the relief that the operation gave Sudha, she would be handicapped for life, with movement deficiencies on one side.

Dr. Mathai met me after the operation and explained to me the procedure done. He said it was a large tumor and through ‘intra-capsular removal’ much of the tumor was removed. ‘We scooped out the tumor and now only the shell remains. It will take fifteen to twenty years for it to re-grow and cause her any problem.’

I asked him about the excision of the left half of the cerebellum and he said, in a matter of fact manner, that to reach the tumor the left cerebellum had to be removed. She could regain her movement faculties through physiotherapy, he added.

It was a super-efficient girl who came to give physiotherapy. But Sudha’s loss of movement faculties was such that even this girl could not make much headway during the course of our two-month stay in the hospital. But she gave valuable lessons to Sudha on the basics of walking. Walking is so simple and natural for all of us but for Sudha even taking one step forward needed a lot of conditioning and lot of practice.

Sudha was discharged 59 days after her admission. Though the discharge summary said she was ‘ambulant,’ she could not in fact stand up or take one step forward unaided. But we were so fed and so exhausted by the events of the past two months that we were looking forward to the discharge. We hoped that with medication and physiotherapy continuing at home Sudha would soon regain her normalcy. It was not to be.

~*~

Problems started earlier than I expected. Despite the physiotherapy, despite the loving care and attention of all members of the family there was not much improvement in Sudha’s condition. On the contrary, there was marked deterioration of every faculty. Gradually she began to slip. And slip in every way. She had difficulty in swallowing, saliva was always dripping from the mouth, and whenever she ate something, food particles entered the windpipe, causing untold discomfort and prolonged, raucous cough.

When the condition deteriorated further in the next few months, a local neurologist suggested that we take Sudha to Chennai for a C T scan. The K J Hospital at Chennai had by then installed south India’s first C T Scan equipment.

The trip to Chennai this time was worse than our earlier trip. At the airport Sudha was taken in a wheel chair from the car to the aircraft. Four porters then bodily lifted the wheel chair with Sudha up the ladder and into the aircraft. This feat was repeated at Chennai airport also.

The C T Scan was taken in the morning and the KJ Hospital doctors gave me the report shortly thereafter. And it exposed a great lie.

The Scan showed that the entire tumor mass was still there. Nothing had been removed except for a little bit, which they said was obviously taken for biopsy purposes. The Scan result exposed the hollowness of the Vellore claim that almost the entire tumor had been removed intra-capsularly and that only the shell remained.

And Sudha was back in square one, needing another operation without much delay.

I took the scan to Dr. P Narendran, head of the neurosurgery department of the Government General Hospital in Chennai with the request that he do the operation. He agreed that Sudha’s condition called for an early operation, but said it would be better to have the same surgeon to do it as he would be familiar with the route he had taken during the previous outing.

That meant zeroing in on Dr. Mathai, once again. Leaving Sudha in the hotel room in the company of the attendants who came with us, I took a taxi to Vellore. Dr. Mathai saw the scan and said a matter of fact manner that Sudha needed another operation. He asked me when I would be able to bring her for admission. I told him I would call him as soon as I returned to Chennai.

Back in the hotel room, however, there was a change in the plans. Sudha was adamant that come what may she would never go back to Vellore. I knew there was no point in trying to persuade her.

On our return to Thiruvananthapuram the next day, I contacted some doctor friends who gave me a new idea. If Sudha would not go to Vellore, the possibility of getting Dr. Mathai to Thiruvananthapuram for the operation should be explored. But for that the government’s permission was necessary.

Pursuing that possibility I met the then Health Minister, Mr. Vakkom Purushothaman, and explained to him the situation. He said the government would accord its permission, but the formal request for the services of a surgeon from outside should come from the concerned surgeon in the Medical College Hospital. He asked me to meet Dr. M Sambasivan, head of the Neurosurgery Department of the Thiruvananthapuram Medical College Hospital.

That was the first time I was meeting Dr. Sambasivan and I went to his house along with a relative who was the head of another department in the Medical College.

Dr. Sambasivan’s visit to my home to see Sudha was, for me, an unforgettable experience. In the car I had explained to him everything about her condition before, during and after the operation. He had a thorough examination of Sudha, saw all records and then had a chat with me and other relatives in an adjacent room, out of hearing by Sudha.

He said normally surgeons were reluctant to requisition outside experts, but in the present case he would be very happy to seek the services of Dr. Mathai. Dr. Mathai was one of his teachers in the Vellore Medical College where he did his MCh. But there was one thing he would like to clarify. He knew the style of operation of Dr. Mathai. He was extremely careful in his operations but was reluctant to take risks. If he thought that going beyond a point was risky, he would stop the operation there. In such cases the patient would get some relief, the relatives would be happy and the hospital statistics would be intact, as there would be no death on the operation table.

“My style is drastically different. When I do a tumor operation, I go for the entire tumor. In ninety-five per cent of the cases my patients may die on the table. But the five per cent that survives would be able to lead a sufficiently normal life. They would be able to dress by themselves, eat without assistance......”

“It is for you to decide whether I should seek the services of an outside surgeon or not,” he told me.

It was indeed a difficult choice. But I told him then and there, with prayers on my lips and tears in my eyes, that I was opting for that five per cent.

~*~

When Dr. Sambasivan was examining Sudha the first thing he did was to part her hair on the left side of the head to look for the operation scar behind the ear. He did not find any. When he found the scar at the back of the skull, he said to himself ‘O, it is midline.’

While taking him back I referred to his search for the scar behind the left ear and asked him whether a lateral approach would have saved the cerebellum, the same question I had put to the junior surgeon in the Vellore Hospital a year ago. Dr. Sambasivan was ambivalent in his reply. ‘No, No, you see, there are different approaches and different methods.....’

But when he did the operation two weeks later, in March 1981, he had taken the lateral route. The incision was made on the left side of the skull, behind the left ear, and the entire tumor, including its shell, was removed. The surgical notes said ‘total decompression done.’

The effect of the operation was dramatic. For several months before the operation, Sudha’s speech had been extremely slurred. Nothing she said could be understood. But when a fully conscious Sudha was being wheeled out of the recovery room after the operation, it was evident that the operation was a great success. For, in a crystal clear voice Sudha asked me, pointing her finger at the big bandage on the left side of her head: ‘Did they do the operation on the correct side?’

It is more than three decades now after that operation and Sudha is as normal as can be expected in such cases. The Vellore operation and the removal of one half of the cerebellum had given her a permanent disability of imbalance in walking. She cannot walk unaided. It was with the help of prolonged physiotherapy that she mustered the strength and the ability to move about with the help of a walker. And gradually she even dispensed with the walker and started moving about the house pushing a plastic chair, which seemed to give her more stability. Risks are there as despite utmost caution there is an occasional fall. And some of the falls in the course of the last three decades had been serious enough to cause fractures.

But Sudha is undeterred. Always cheerful, though in a subdued manner, never complaining about her condition, constantly praying, she moves about the house, in her own imperfect way, taking care of everyone’s needs as a perfect home-maker. With indomitable courage and unassailable willpower.

And I thank God for giving her back to me at least in this way.

24-Nov-2013

More by : P. Ravindran Nayar

|

Thank you, Sosanna, for you heart-warming comment. Ravindran Nayar |

|

"There's nothing Love cannot face: there's no limit to its faith, its hope, and its endurance." ( St.Paul ) This a testament to Love: that two united as One, can make mountains move. |

|

Thank you, Madhu, for your kind comments. |

|

Straight talk from the heart - good one from you sir. Many events in life are quite unpredictable. Fortunately majority are positive or neutral to make us go on in this life. Our own misfortunes may come through a second or third person, most of the time unintentionally. Dr. Sambasivan sir had told you the truth. Now I remember a medical student with the same problem - Acoustic neuroma, went to a distant place to get the best surgeon and in the attempt of total removal of the tumour, lost the patient on the table, that's what I heard. Even a minor surgery has it's risk, starting from the induction of Anaesthesia. In your case your's and your wife's courage and partial luck gave you at least some comfort at the end. Madhu |

|

Thank you, Krishna Kumar, for your kind comments. |

|

A poignant narration of the trials and tribulations that you both had to endure. The repeated botch up by the so called specialists and the tragic effect on her is really heart wrenching. Her spirit is indeed remarkable and you have been a tremendous pillar of support. |

|

Thank you Kushal, Seetharam and Vistasp. I am grateful to you for your comments and good wishes. |

|

What an incredible, heart-stopping real life story. And thank heavens that despite everything, it ended reasonably well. Mr. Nayar, I am sure what you have managed to put forth in your lucid and touching account is possibly a mere fraction of the roller-coaster of a journey you must have been a part of. I can't help but commend you for the dignity, stoicism and courage with which you have dealt with this in your life. May you both enjoy years of togetherness and bliss, in the years to come as well. And thanks for writing this to make the rest of us appreciate the complexities of life and companionship a little better. |

|

Mr. Nayr had a harrowing experience indeed. The dilemma he faced at that time and the pangs of the feeling of having taken a decision which proved unwise later are beyond words.Often fate plays its hand to toss you to misfortune or sometimes to fortune. In medical cases it is thought prudent to obtain a second( or even third ) opinion. But more often than not this leads to a lot of confusion and consequent dilemmas. Doctors differ in their opinions and one is left bewildered as to whose advise to follow.Difference of opinion is natural but it goes to the extent of scorning other opinions.If only they had the goodness and grace to hold consultations among themselves and put their heads together to arrive at a common diagnosis the patients would definitely be benefited. But ego and professional jealousy supersede Hippocrate's oath. CMC Vellore has the reputation of being a high class referral hospital and Mr. Nayar had gone there on the advise of friends in the medical profession. Everything should have gone well but fate had something else in store for Mrs. Nayar. The secrets of human destiny baffles reason and one feels sceptical of the saying'man is the maker of his own destiny' |

|

A very heartwarming and inspiring story of hope and human will. Hats off to you for showing such courage and determination that brought Sudha back from hell. |