Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

While the Buddhist influence in India is often thought to be at Nalanda, Ajanta and Sanchi, a primary seat of Buddhism was at Gandhara, under the Kushan dynasty, in the vicinity of modern day Peshawar. First ‘discovered’ by British army officers in the 19th century, Gandhara art and architecture displays considerable Greek influence which may have been due to its interactions with Bactria in the 4th century BC. Two main sites where Buddhist monasteries have been found are at Takht-i-Bahi and at Jamalgiri. These display a singularly stark departure from the ‘simple’ viharas at Ellora and Karle, and show a certain level of sophistication in planning and layout.

While the Buddhist influence in India is often thought to be at Nalanda, Ajanta and Sanchi, a primary seat of Buddhism was at Gandhara, under the Kushan dynasty, in the vicinity of modern day Peshawar. First ‘discovered’ by British army officers in the 19th century, Gandhara art and architecture displays considerable Greek influence which may have been due to its interactions with Bactria in the 4th century BC. Two main sites where Buddhist monasteries have been found are at Takht-i-Bahi and at Jamalgiri. These display a singularly stark departure from the ‘simple’ viharas at Ellora and Karle, and show a certain level of sophistication in planning and layout.

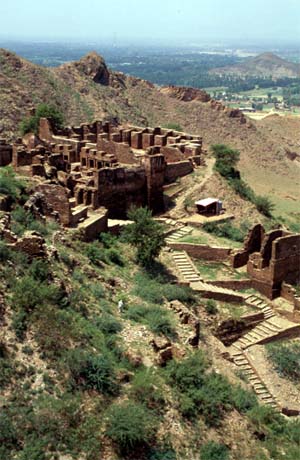

The ruins of the Takht-I-Bhai (Takht means seat or throne and Bahi means reservoir) monastery from the Gandhara period cover an area of about 33 hectares, in northwest Pakistan.

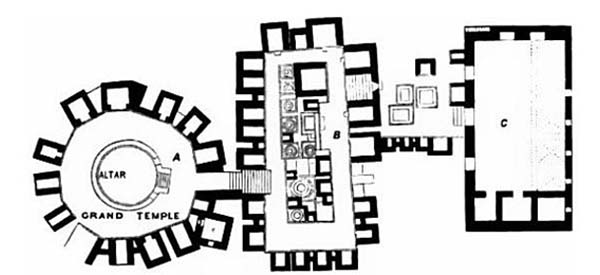

Illustration of Monastery at Jamalgiri. Source: James Fergusson, c. 19th century.

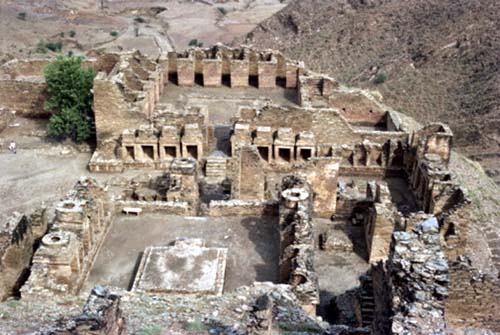

There are certain plan-form similarities in both these monasteries which may be summed up as follows: the first architectural disposition, just after the entrance, is a square or circular court surrounded by cells, much like at the viharas at Ellora. It is to be noted that none of these cells is really large enough to accommodate a person, and so it is believed that they were originally used to contain images, though none were found at the time of discovery. In the center of this court is a platform, once again square or circular, and it is approached by a series of steps. Carvings on the side of the platform depict the Buddha or simply a row of pilasters.

Monastery at Takht-i-Bahai. Rough sketch.

The entrance court leads by a narrow passage to the next court, which is more rectangular in shape, once again surrounded by cells containing images, and finally this leads to the main vihara which is actually used for accommodating monks. This series of spaces, or architectural ‘promenade’, is really what distinguishes the Gandharan monasteries from the ones at Ellora and Ajanta, the latter having no equivalent of the initial courts containing cells with images. Other distinguishing features of the monastery at Jamalgiri is the presence of a series of bas-reliefs, containing tales from the Jatakas, which embellish the steps leading from the first court to the second. Links with ancient Greece and the Bactrians may be easily determined, with the presence of a large number of Corinthian capitals, though it is difficult to say where they were exactly intended to be used inside the monastery. It is entirely possible that the capitals, and indeed the front and interior spaces of the monastery, were adorned by fresco paintings such as the ones at Ajanta, thus giving the monastery a very different look from the drabness in which it was found.

If the monasteries at Takht-i-Bahi and Jamalgiri represent Corinthian Greek influences, then there are also structures which have taken inspiration from Ionic capitals and ornamentation. A tiny monastery at Shah Deri, once again near Peshawar, illustrates this quite well. Here the interior is small enough to accommodate no more than 2 or 3 people at a time, with pillars in the center of the spaces being decidedly Ionic in form and proportion.

What is the age of these discoveries, and why was the Greek influence so strong? Current dating puts the age of these monasteries as between the 3rd and the 1st centuries BC, and it is conjectured that Bactrian Greeks, during their brief period of rule over this part of the subcontinent, carried these forms with them to India. Later, during the age of Kanishka and the rule of the Kushans, this influence was carried through into Buddhist monasteries of the period.

Another distinguishing feature of these Corinthian and Ionic capitals is the presence of carved small images of the Buddha and other leaders of the Buddhist pantheon, a detail which is not repeated in Ajanta and Karle, once again attributing to these monasteries a very unique identity in their proclamation of the physical essence of the Buddha. It is probable that these figures date later than the monasteries themselves, since there are almost no instance of carved Buddha images that date before the 1st century BC.

Dharmarajika archaeological site, Taxila excavations, Gandhara, Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan

Colonial historians have gone so far as to suggest that it was the Greek influence in Gandhara that may have led to the widespread use of idols in India, and even to say that Indian epics bear in them traces of Greek and early Christian culture. It is undeniable that Gandharan Buddha images bear traces of the Greek influence, especially in the so-called ‘wet drapery’ style of the graven images of the Buddha. But it is difficult to believe that this influence could have been only in one direction: indeed, as the transfer of the decimal system from India to Europe via the early Arabian civilization has shown, the most probable conclusion is that the Greek invasion, and subsequent rule of the Gandharan region by the Kushan kings, led to a far greater mixing of cultures than normal geography would allow, and was a change from the later insularity of India under the Gupta Empire.

Much of the Gandharan heritage has been lost: the early Islamic settlers in this region were assiduous in wiping out images that they felt represented human beings, and in modern times the giant statues of the Buddha at Bamiyan in Afghanistan were destroyed too. However, this region is a vital link to India’s past and its interaction – and influence of – the Western world via the Bactrian Greeks and the Kushan Empire.

Images (c) Gettyimages.com

24-Nov-2013

More by : Ashish Nangia