Feb 07, 2026

Feb 07, 2026

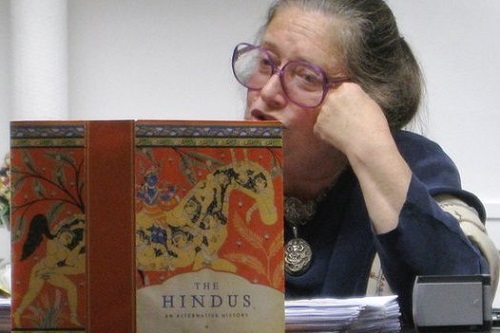

Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: An Alternative History, Penguin, 2009, pp.780, Rs.999

From the Vedic people in the Land of Five Rivers to the Hare Krishnas in American airports – “a history” not “the history” of the Hindus

Belying its formidable bulk, Doniger’s latest tome spread over 25 chapters turns out to be an unexpectedly enjoyable experience because of the unusual approach adopted in presenting Hinduism (first used possibly by Rammohun Roy in 1816 she informs) to the American students. Avoiding the pitfalls of Orientalism, she merges the chronological and the thematic in her survey, starting each chapter with a chronology, then proceeding to elaborate the theme of the period. Her style flows along, inimitably chatty, bearing the immense load of scholarship ever so smoothly. The historical picture draws almost exclusively on Romila Thapar and John Keay, reflecting their bias. Admitting that “such a luxurious jungle of cultural phenomena …necessitates a drastic selectivity”, she presents “not a seamless narrative…but a pointillist collage…Synecdoche—letting one or two moments in history and one or two narratives stand for many—allows us to see alternity in a grain of sand.” That is why it is “alternative” as “a”, not “the” history of Hindus. Its value also lies in using not “the basic curry and rice episodes” but excerpts from lesser-known texts revealing what religious life was like for ordinary people and interactions with non-Hindus. With a minimal backbone of basic historical events, she moves away from social history to literary texts about alternative people, balancing “the smoke of myth with the fire of historical events,” showing how myths can drive events, for ideas are facts too (e.g. the belief regarding greased cartridges that ignited the mutiny in 1857).

Doniger uses her favourite device of a Zen diagram without a central ring as a metaphor for Hinduism: One person’s centre is another’s periphery. Indulging her penchant for word-play, she describes Hinduism as “a polythetic polytheism which is also a monotheism, a monism and a pantheism.” She also uses for it the “bricoleur” image, a rag-and-bones man, building new things out of scraps of other things, as Hindus did temples and Muslims mosques out of Buddhist stupas or other temples. “There are no copyrights here; all is in the public domain,” writes Doniger. She sees an eclectic pluralism prevailing, a kind of cognitive dissonance in which a person holds a toolbox of different beliefs simultaneously, picking out the one she finds appropriate for the occasion. Thus, Manusmriti condemns and advocates meat eating with equal force in chapter 5; Mahabharata has the holy butcher, the virtuous hunter and the housewife whose “tapas” shames an ascetic. An individual may regard herself as a fused hybrid: fully Muslim in some ways and fully Hindu in others, celebrating both Muslim and Hindu festivals, visiting both dargahs and temples, worshipping both Satya-Pir and Satya-Narayana.

Doniger suggests that the existence of texts repeatedly stressing that women should not read the Vedas suggests they used to do so. Rig Veda (RV) 10.18 urges a widow to rise from beside her husband and be in world of the living. A valuable summary of dialogues between women and men in RV is provided. The beheading of Dadhichi for teaching the Veda to the Ashvins who are linked to farmers and cattlemen shows that it was not merely an anti-women and anti-Shudra stance. The success of Vishvamitra, a Kshatriya, in attaining Brahmarshi status chronicles the fluidity of the class system. She cites the change in the myth of Urvashi as an instance of attrition in women’s independence. But why should the reunification of Urvashi with her husband in Shatapatha Brahmana signify this (in RV she leaves her husband when he violates her condition)? While rightly comparing this to Ganga leaving Shantanu after drowning their seven sons, Doniger overlooks the many Apsaras who desert their newborn children. In the Upanishads she finds individualism in the wives (Katyayani and Maitreyi) and Gargi. Doniger informs that the unseen Katyayani appears as a jealous co-wife in Skanda Purana 6.129, performing a ritual to Parvati that makes her Maitreyi’s equal in their husband’s eyes. The Kamasutra reveals a pro-feminist view of women’s plight. While noting the “ironic” presence of women in Mahabharata, beyond earshot but definitely heard, she overlooks that the chief “movers” of the plot are Satyavati, Kunti and Draupadi. The royal lunar dynasty is replaced by Satyavati’s lineage, which in turn is displaced by Kunti’s through a war set-off by Draupadi.

Doniger’s unique viewpoint is to highlight three charismatic animal players in the drama of Hinduism symbolising power (horse), pollution (dog) and purity (cow). The horse was rare, therefore ritually sacrificed. It was linked to Muslims, like the cow was to Hindus, the buffalo to evil and the mare to the femme fatale. Doniger overlooks that the docile cow routs Vishvamitra’s army and that this sage is also linked to dog-eating. The significance of the Mahabharata having dogs at its start and at the end has been ignored.

Each Hindu sect acknowledged the existence of gods other than theirs suitable for others to worship. Hence, Doniger suggests, Hindus may best be called “polydox”. RV 7.104 curses those accusing others of worshipping false gods. The creation hymn (10.129) daringly states that perhaps even the supreme deity does not know who made the cosmos. So too, 10.121 asks, “whom should we worship with oblation?” However, this ignores Ashoka rewarding the killing of thousands of Jains in Pundravardhana; the bloody feuds between Shaiva and Vaishnava monks [18000 sadhus were slain at Hardwar in the 1760 Kumbha Mela], even between Shaiva Giris and Puris. The Rajatarangini calls a Hindu king a Turuska for plundering temples and strewing excreta and liquor over statues of deities.

While overlooking the Gita’s assurance that whatever be the form of worship, it is the Supreme Divine who receives the devotee’s offering, in three pages she provides an excellent summary of the core of its message and significance. There is a fine discussion of how geography influences culture in India—the variety of sources and the power of the integrations, e.g. the Tamil story made much of by Western Indologists who are fond of using it as a symbol of India’s peculiar pluralism: of a Brahmin head and Pariah body of Mariamma vis-a-vis Ellamma’s Pariah head with Brahmin body, the former getting offerings of goats and cocks, the latter of buffalo.

She provides a fine review of the Indus civilisation which “is not silent but we are deaf for we can’t hear their language.” The Vedas, conversely, are words without physical evidence about the people. Vedas do not mention tigers, rhinos familiar from IVC seals; regard elephant as curiosity and create a word for it meaning “mriga-hastin—animal with a hand), no unicorns. So these people lived north of the land where the tiger, elephant and rhino roam. However, the horse features prominently as in all Indo-european cultures. Rightly, she notes the absence of Hinduism’s favourite animal the cow, horses, cats and suggests that the supposedly erect phallus of the horned figure in seal 420 could be just a knot in the waistband—a good example of the vedantic snake-or-rope trope. She questions why the female figures found must symbolise fertility and some ritual. Why must the Mohenjo-Daro great bath be a ritual tank? Such conclusions remain tentative because the structure east of the bath was not excavated as a Buddhist stupa stands there (Marshall thought of getting all the workmen to stand on it to be photographed, hoping it would collapse) buried under many layers of Indus mud, which may have inspired the myth of the great flood of Shatapatha Brahmana (c.800 BC). Doniger warns against reading the past through the present, as if contemporary Indian society was a guide to “timeless” India’s past.

Doniger argues that six things in non-Veda cultures gave birth to new ideas, stories, practices in the Sanskrit world: stone age cultures; Adivasis; IVC; village traditions; Tamils and other Dravidian speakers. The early Veda is envious of Dasas’ plentiful cattle, but later the word denotes a servant and late parts mention Brahmins who were dasi-putra (Vyasa himself). The Brahmanas question the concept that class is by birth and state that knowledge being the father and grandfather of a Brahmin, there is no point enquiring who his parents are. Kavasha, son of Ilusha, is driven away being a slave woman’s son, but has to be accepted when he composes sukta 10.30. Dasas may have introduced new ritual practices as in the Atharva Veda.

Gambling with dice, chariot racing, hunting, liquor, sex feature prominently all through Indian literature and are linked to downfall of kings and commoners (RV 10.34 speaks of the gambler’s wife becoming woman of other men, as with Draupadi).

While glossing “Shachipati” as “master of power” Dongier overlooks that as daughter of the Danava king Puloman she is a link that characterises gods as well as the lunar dynasty (Yayati is the dynast through the Asura princess Sharmishtha).

The greatest fear is that of old age and death and, most of all, the series of re-deaths due to rebirths. Doniger does not mention the most poignant instance of this—Yayati. Immortality does not mean eternity, for even gods do not live forever. Rather, the full life span of 70 or 100 autumns is celebrated. Doniger fails to explain what Hindus meant by immortality.

The Brahmanas indicate a geographical shift to the Ganga-Yamuna Doab around 1100-1000 BC. Then around 900 BC it veers to farther down western and middle Ganges valley followed by the birth of powerful kingdoms like Kashi, Kaushambi between 1300-1000 BC. The Brahmanas were composed centuries after these cities were founded. The initial movement was from Punjab eastwards to Magadha in Bihar and lower Ganges, later westwards from Ganges to Gujrat. Iron is brought into use from 800 BC in the western Ganges plain and southern Bihar. “Bali” was tax paid to kings, which alienated people. People are described as food for royal power; people’s son cannot become king (Shatapatha Brahmana).

Whatever food man eats in this world, eats him in the other world. The soundless scream of rice and barley that the Jaiminiya Brahmana speaks of resurfaced in writings of JC Bose who demonstrated it to G.B. Shaw. The Shatapatha prescribes killing a bull or a cow for a guest, 21 sterile cows to be sacrificed in Ashvamedha for “the cow is food” (Taittiriya Samhita). Apastamba Dharmasutra states that the meat of milch cows and oxen fit for eating. Cattle bones have been found at domestic hearths excavated, also human remains at fire altar sites. This is not just pre-Vedic/Vedic, but is referred to in the story of Jantu in Mahabharata and of Shunahshepha’s rescue from being sacrificed in the Aitareya Brahmana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana.

Around the same time as Shvetashvatara Upanishad’s image of the senses as horses and the intellect as charioteer we have the identical image in Plato’s Phaedrus. By this time there is difficulty in obtaining Soma as seen in the Brahmanas which cite substitutes.

Doniger provides a fine explication of six meanings of karma, of moksha. Upanishadic thought shows a radical break with the Vedas by encouraging taking to the path of moksha as soon as possible. She suggests that these Sannyasa Upanishads were probably by fringe mystics, the Vratyas, who rejected sacrificial ritual in favour of acquiring spiritual knowledge through asceticism, renunciation, yoga.

The Brahmanas and Upanishads sow the seeds for abandoning animal sacrifice: the gods are sated merely by looking at Soma nectar and accept oblations of vegetables. Thus Hinduism answered the challenge of the anti-sacrificial polemic of Buddhism and Jainism, further reinforcing their case by the theory of re-incarnation.

For Hindus there is no tension between eroticism and renunciation, the saguna creator and nirguna Brahman, the latter being a force for tolerance. It is one house with many mansions: householders support renouncers to gain second-hand merit. The concept of non-violence supplemented, did not replace, blood sacrifice. Time and again the road forks, writes Doniger, but the two paths continue side by side, sometimes joining, then diverging again, and people can easily leap from one to the other at any moment. Asceticism ricochets against addiction and back again. She quotes from Philip Roth’s “I married a communist” to explain to the western reader the psychology of the forest-dweller stage. The drive to hierarchize the aims of life overrides the drive to present a serial plan or a single alternative for a well-rounded life. The Mahabharata holds that the householder’s life is supreme while most other texts rank moksha as the highest. Doniger finds Hinduism trapped in a basic social paradox: how to reconcile sva-dharma with universal dharma? The plurality characterising Hinduism is validated by endorsing the former: “Sva-dharma trumps general dharma.”

A very interesting question is posed: How different would the lives of Indian women have been had Draupadi instead of Sita been their official role model? A fascinating alternative scenario could be developed on this basis. There is also the heroic Savitri who successfully wins her husband back from death.

Doniger’s discussion of the epics contains exceptionally revealing insights. She shows that where Ramayana is triumphalist, Mahabharata is tragic; where Ramayana is affirmative, Mahabharata is interrogative. She points out a feature that we do not notice: though Sita is Lakshmi incarante, she is not reunited with Rama as Vishnu despite Brahma’s assurance when he rebukes Rama for doubting her. Everyone is present to welcome Vishnu’s return to Vaikuntha except Sita. There is also a difference in how the rakshasa women are treated in the two epics. Where the brothers mutilate Shurpanakha (nose and ears) and Ayomukhi (breasts, nose, ears), Bhima marries Hidimbaa and has a son by her. Doniger’s claim that while Sita is an epitome of female chastity she is also a highly sexual woman (which is why Ravana desires her) is not unfounded. Read the passage where the disguised Ravana praises Sita’s sexuality to her face without her objecting in the least. Elsewhere Sita muses over her own physical perfection in detail while wondering why, despite this, she is suffering exile.

Analysing Rama’s psychology, Doniger proposes that he kills Vali as in Sugriva he finds an expression of his rage against father and step-brother. The monkeys are parallel lives, presenting a variant of the life of Rama as in a dream, the animals replacing people about whom dreams express strong repressed emotions. Poetry functions as dreamwork, reworking repressed emotions and projecting them onto animals. As perfect son and brother, Rama cannot express his resentment of his father and stepbrother. The monkeys do it for him. In the forest, his unconscious mind is set free to take the revenge his conscious mind does not allow in the human world. Actually, Vali is his real double, as he has recovered throne and wife from the usurping younger brother (in 2.16.33, Rama says he would gladly give Sita to Bharata). She argues that the text “doth protest too much” in insisting that Lakshmana will not replace Rama in bed with Sita. Notice that when Rama rejects Sita he says she can go with Lakshmana. Ultimately, Rama does condemn Lakshmana who commits suicide.

Doniger proposes that Mahabharata’s Hastinapur was a great city in the age of the Brahmanas while Kashi in Koshala was settled later, but does not cite evidence for this. The Mahabharata does look back to Vedic age, dressing its stories in Vedic trappings. Its geographical setting, she asserts, predates the Ramayana—but on what basis? Mahabharata is about building a great empire that is more Mauryan than Vedic, often referring to a quasi-Mauryan Arthashastra, reacting to currents of Buddhism and Brahminism of the Sungas. It seeks to reconcile political flux with the complex values of emerging dharmas. Brahmin redactors of Mahabharata created a text that accepted the political implications of the violence of the universe in part precisely in order to distinguish themselves from the nonviolent Buddhists and Jainas. Yudhishthira is seen as a Brahmin king like Pushyamitra Sunga, or a Buddhist king like Ashoka, or both.

Doniger errs in stating that Yudhishthira alone goes to heaven in his own body, overlooking the passage she quotes on p.281. While making much of his loyalty to the dog, we forget that the dog does not enter heaven. Serious doubt is cast on the glory of the horse-sacrifice and the black-magic (abhichara) ritual of snake sacrifice. Mahabharata sees a vice behind every virtue, a snake behind every horse, and a doomsday behind every victory. It deconstructs dharma, exposing the inevitable chaos of the moral life. “Brahmins were circling the wagons against the multiple challenges of Buddhist dhamma, Ashokan Dhamma, Upanishadic moksha, yoga and the wildfire growth of Hindu sects.” Before Buddhism, there had been no need to define dharma in detail, but now it was necessary as Buddha called his teaching the dhamma. “What is dharma? asked Yudhishthira and did not stay for an answer.” The Apastambha Dharmasutra 1.7.20.6 states: Dharma and adharma do not go about saying ‘Here we are”; nor do gods, Gandharavas, or ancestors say, “This is right, that is wrong”. The solution? It is an impasse! Aporia is erased through the device of the experience of hell being just a dream and by the intervention of gods. “The Mahabharata is thinking out loud, still trying to work it all out about fruits of karma, rebirth, worlds beyond which there is nothing—the jury is still out.” How classes came about is quoted from Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva: actions divided people into classes. Rajasic Brahmins became Kshatriyas with red bodies. Those herding cattle and ploughing became yellow Vaishyas. Those greedy, fond of violence and living impurely became black Shudras.

To Doniger, the Mahabharata women are “a feminist’s dream: smart, aggressive, steadfast, eloquent, tough as nails and resilient and polyandrous.” She proposes that the text was shaped during the Mauryan and post-Mauryan period when constraints on women loosened. Royal women generously donated to the Buddhist community; women from all classes including courtesans turned Buddhist; women archers formed the royal bodyguard and served as spies; female ascetics moved freely; prostitutes paid taxes.

Doniger corrects a widely prevalent misconception regarding Ashoka’s espousal of non-violence. Actually, he permitted the limited killing of three animals daily; did not discontinue capital punishment or torture. She overlooks his execution of his queen Tishyarakshita for engineering the blinding of his son Kunala. Further, Ashoka ordered that all the followers of Nirgrantha Gyatiputra in Pundravardhana be executed. 1800 were thus slain. Then he proclaimed a reward of a deenaara (gold coin) per head of a heretic. These are recorded in the Sanskrit “Ashokavadana”.

Although Hinduism has no canon, says Doniger, the Brahmin canon could be the shastras setting up paradigm regarding women, animals, castes. Foreign flux in the early years AD made knowledge more cosmopolitan regarding food, dress, thoughts, but also posed a threat leading to tightening up of social control. Early AD is India’s Dark Age, lacking a properly governed empire and little sources of history. On the other hand, she suggests that the pre-imperial age was one of diversity rather than of invasions by mlecchas. A rich cultural integration occurred, a creative chaos inspiring scholars to gather all knowledge to preserve it for posterity. The art and literature was richer then than during the earlier Mauryas and the later Guptas.

In Manu’s Dharmashastra one sees an attempt to dovetail castes within class structure. To Doniger it is a masterpiece of taxonomy though purely imaginary as there is no evidence that jatis developed out of varnas. Manu unites the Vedic tradition of sacrifice and violence with the later tradition of vegetarianism and nonviolence, synthesizing them. The text even says that a horse-sacrificer and one who does not eat meat reap the same fruit of good deeds.

An interesting controversy emerges over the gandharva marriage by mutual consent (today’s “love marriage”) which is ranked as the best by Vatsyayana and Manu, but which Kautilya classes as the best of the bad marriages (followed by dowry, rape, drugging, sleep). These display a range of opinions on how to treat brides, some showing the earlier freedom of women, others the narrowing of women’s options, even legitimizing rape (Arjuna’s of Subhadra being advised by Krishna). Doniger finds that Manu is not so much a law code as a dissertation on problems raised by codes. It is a Brahminical vision of what human life should be. But the Kamastura’s warning should be kept in mind: the existence of a text for a practice does not justify that practice.

Generally the Bhakti movement is seen as reforming the Hindu social system. Doniger points out that actually it created an alternative system, as Buddhism, Jainism etc. had done. Many leaders came from lowest classes, but subsequently caste reasserted itself: Ramanuja, Chaitanya failed to eradicate it and Shri Vaishnava Brahmins invented stories to disassociate Nammalvar from his Shudra origins (e.g. refusing milk of his Shudra mother’s breast). Despite the strong antipathy to sacrifice, violence was often perpetrated against Hindus refusing to worship the chosen deity e.g. Nayanmars fighting Jains or killing their own relatives. The god often tests the devotee by asking him to cook his child’s meat for a guest. It is capped by the parents being taken up to heaven of course. Bhakti strangely went hand-in-hand with fanaticism. Mihirakula and Sasanka destroyed Buddhist monasteries and killed monks; Alvar Tirumankai stole a Buddhist image and used the gold for the gopuram at Shrirangam. Hymns of Alvars and Nayanmars are strongly anti-Buddhist and Jain.

A little known fact is brought up by Doniger: Jews were in Malabar since 70 AD. St. Thomas went there in 52 AD after working in the palace of the ruler of Gandhara. After the Prophet’s death the Mapillai Arabs settled in northern Malabar trading with Chalukyas and Cheras bringing horses. Vijayanagar imported 13000 horses annually in the 16th century and 10,000 Arab and Persian horses entered Malabar every year, vital for the virility of Muslim rule imported from central Asia. Marco polo in 1292 records the Pandyan ruler of Madurai importing 2000 horses annually. Huns cut off trade routes in north and vital supply of equine bloodstock from central Asia, so the Muslim rulers had to import from Arabia, which was very expensive.

A controversial proposition made by Doniger is that the idea of surrender, prapatti, central to the Shri Vaishnava tradition may have been influenced by Islam which means surrender. For the public in ancient south India, religious pluralism was more of a supermarket than a battlefield. Lay people gave alms to Buddhist monks, prayed to Sufi saints, visited Hindu temples. Unlike Buddhism and Jainism, Hindusim was not a proselytizing religion. A person had to be born a Hindu. Bhaktas, however, proselytized furiously. Even Shiva had to become a shaiva, bhakti’s violent power compelling even a god!

Gupta art is pretty but lifeless for Doniger, not vigorous as the preceding Kushana and later Chola, and imitating Hellenistic art which is second rate Greek art. Quite correctly she points out that the greatest architectural monuments were created not in Pataliputra but in remote provinces: Ajanta, independent of Gupta control. Religious diversity was encouraged: Chandragupta II patronized Buddhism and Jainism in annual festivals. Huns were anti- Buddhist and killed monks, destroyed monasteries in Kashmir and Punjab and right up to Gwalior in the 5th century AD. Shaiva Brahmins who accepted land grants from Huns were equally hostile to Budddhism. This period saw the Puranas reworking folklore and epic materials to become “the pulp fiction of ancient India.” The non-Vedic traditions supplied the major substance of the Puranas. Growth of temples led to greater use of ritual texts (agamas). In temples people would access myths and rituals through carved images regardless of caste and gender. Thus the Puranas cut across class lines and had wealthy merchants as patrons (where is the evidence for this?). No Brahmin priest was essential for puranic rituals. Brahmins were of various ranks now, by geographical location or degree of learning—even ogre-Brahmins, Shudra Brahmins, Mleccha Brahmins, Nishada Brahmins (e.g. in the Garuda story).

Doniger finds the popular trinity concept of the Puranas mistaken as both Vishnu and Shiva create and destroy. Further, Brahma is not worshipped like them as creator. The Puranas begin to tell stories about goddesses and a mythology takes shape. All goddesses are not mother goddesses. Parvati does not bear Skanda and Ganesha. She curses wives of gods to be barren.

There are several little-known facts that Doniger highlights: in Harivansha (118) Janamejaya curses Indra that none will offer a horse-sacrifice to him. Arthashastra states (1.6.6) that Janamejaya perished having whipped Brahmins, suspecting them of violating his queen in the horse-sacrifice. This might reflect a historical fact that Vedic Indra was no longer worshipped in the Puranic period. A good parallel is Daksha’s sacrifice that shows non-Vedic Shiva was not being worshipped till the Puranic period. By then, kings had shifted from horse sacrifice to endowing temples. The Puranas expand on Mahabharatan concepts of transfer of merit, periodic stay in heaven and hell and celebrate tirthas as the means to avoid tortures of hell. For instance, to expiate the sin of Kurukshetra, Yudhishthira is told by Markandeya to bathe in Prayaga (Kurma Purana 1.34), whereas in the Mhabharata he performs a horse-sacrifice for this. The Markandeya Purana has Balarama wash away the sin of drunkenly killing Suta by undertaking a pilgrimage from the mouth to the origin of the Sarasvati.

Doniger reveals that Brahmins legitimized foreign rulers to get temporal support for themselves, as seen in a 1369 AD inscription tracing the descent of a sultan to the Pandavas. A 1491 AD inscription depicts Turushkas, Shakas, Mlecchas shouldering the burden of the earth, relieving Vishnu of worries! There are fascinating instances of communal amity that Doniger cites. The Ranganatha image of Vishnu was taken away by Malik Kafur. The sultan’s daughter fell in love with it and was either absorbed into it or died of a broken heart when it was returned to the temple. Even now image is offered puja with food cooked in north Indian style. Under the sultanate a Hindu inscription of 1280 AD praises the security prevalent under Balban. Md bin Tughluq had muslim officials repair a Shiva temple and allowed anyone paying jizya to build temples. In Kashmir (1355-73) the sultan rebuked a Brahmin minister for his suggestion to melt down Hindu and Buddhist images to get cash. Sultans married Hindu princesses, patronised Hindu artists and scholars. In Bengal, Raja Ganesh’s son converted to Islam and ruled under his father’s direction. His successor Aladuddin Husain revered Chaitanya and was regarded as incarnation of krishna by Hindus. Yet, in Orissa he destroyed temples. Nath yogis and Kapalikas were friendly to muslims. Sufism held all religions were striving to same goal irrespective of outward observances and became major strand of the bhakti movement. In Sufi romances the hero is a yogi, the heroine an Indian woman. Sufis took Sanskrit’s poetic language of emotion and devotion from Krishna sects and much of yoga philosophy. Arabs and Iranians passed on to Europe stories from Kathasaritsagar that became the Arabian Nights (e.g. the plot of All’s Well That Ends Well). Sultans used Hindu temple techniques to build mosques.

In the 15th century the Vijayanagar kingdom established Rama as the major deity. He and Hanuman became the focus. Sects grew up around Janakpur and Ayodhya. No Vijayanagar temple inscription has any anti-Muslim statement. Rama is not seen as hero against Muslims. The temples might have been built as a response to theological challenges posed by Jainas and Shaivas, suggests Doniger. Bukka in 1368 declared that Shri Vaishnavas should protect the Jaina tradition. Doniger sees the extravagant architecture at Hampi, Halebid, Badami as a reaction to Muslim demolition of the Mathura and Kanauj temples. Subsequently, the withdrawal of royal patronage from temples and Brahmin colleges encouraged the spread of the popular form of bhakti.

Doniger espouses Romila Thapar’s proposition that the Jain concept of nine appearances of a saviour in each epoch could have influenced the development of the Hindu schema of nine past avatars of Vishnu. The clash between social evolutionism (things get steadily better) and the yuga theory of social degeneration (things get steadily worse) contradicts Keshub Sen’s declaration that avataras are an allegory of the Darwinian evolutionary process. Text-wise the chronology of the appearance of avatars is: dwarf in Rig Veda, fish and boar in Brahmanas; tortoise, Krishna, Rama, Parashurama, Kali in Mahabharata; man-lion and Buddha in Vishnu Purana (c.400-500AD). Issue-wise Doniger classifies them thus: first animals—fish, boar, tortoise—then women (Krishna-Radha, Rama-Sita), then inter-religious relations (Buddha, Kalki), then caste and class (Parashurama, Dwarf, Man-lion.)

Bhakti texts challenge the fatalistic Karma view: Devaki forces Vasudeva to stop moaning that the killing of their sons is fated and to save her baby. Bhakti believes actions in this life can produce good or bad fortune in this life and that devotion to gods pays off in this life and the next. Harvansha injects the prominence of women in Krishna worship. It extols Yashoda, which the Puranas develop into the Radha figure, making the feminine more important. They also interlink the epic characters by introducing the concept of the shadow Sita’s birth from fire which links her to her re-birth as Draupadi from the fire-altar and Vali’s rebirth as Jara.

Doniger argues that at first Buddhism was assimilated into Hinduism in the Upanishads and the epics. This was a period of harmony among Hindus, Buddhists and Jainas. In the second stage, Buddhists became more powerful and were seen as a threat. In the Gupta period the Puranas denounce “shastras of delusion”, the Buddhist and Jaina teachings. In the third stage, Buddhism wanes; Hindus accept Buddha as an avatar. The 10th century Kashmir king Shankaravarman makes a magnificent frame for an image of Buddha avatar, just as Hindu temples were built on Buddhist stupas and later mosques over temples. Kalki, Doniger proposes, is a reaction against invasions by Greeks, Scythians, Parthians, Kushanas and Huns inspired in part by the future Buddha Maitreya and the image of the purifying saviour brought by Parthians in early AD when millennial ideas were rampant in Europe and Christians were preaching in India. There is the rider on a white horse of the apocalypse putting pagans to the sword. With Kalki’s appearance, the earlier doomsday fire and flood vanish from texts. Vishnu initiates the Kali yuga as Buddha to destroy anti-gods by making them into heretics. Then, at its end, he incarnates as Kalki to destroy barbarians and heretics (Buddhists/Jains). The Kalki Purana is perhaps of the 18th century.

A good question Doniger raies is: why is Parashurama given avatar status? Is it because a fanatical anti-Kshatriya so appealed to Brahmin authors of the Puranas? Or is it to show that birth does not make class. Kshatriya women revive their class through Brahmin men. Thre is also the fact that his campaigns were only against Haiheya rulers, just as king Sagara of Ayodhya eradicated the Talajanghas, another Haiheya clan.

Inevitably, besides her favourite horse, who has already featured in the discussions, Doniger dwells upon the dog. In the Skanda Purana a hunter attains Shiva’s world because he does not kill a dog who eats his food. In the Vamana Purana Vena is cleansed of sin when a dog showers him with water from Sarasvati river. The dog also reaches Shiva’s world.

Doniger shows us how the Yoga-Vasishtha Ramayana deconstructs gender in tale of Chudala and caste in the tale of King Lavana. She further points out that analogous to Yudhishthira, Nala and Rama are exiled among common people to learn how other half lives. This is further elaborated in the Markandeya Purana’s Harishchandra. Rajasthani folklore’s Gugga combines Chauhan Rajput and Muslim as his fair is called Gugga Pir. Tamil and Teleugu legend has as hero Tecinku’s best friend a Muslim who prays to both Rama and Allah and ends up in Vishnu’s heaven. The Muslim Muttal Ravuthan is the guardian for the Draupadi icons in Gingee. Thus, “Vaishnavism encompasses Islam”. Doniger shows that much Muslim poetry begins with invoking Allah but proceeds with Hindu content and imagery.

Rupa Goswami tells Krishna’s life like a Sufi romance in Bhaktirasamritasindhu. Mahabharata heroes and Shahnama paladins interact in Tarik-i-farishta. Muslim pilgrims visited Hindu shrines in Kangra and Mathura while Hindus worshipped Sufi pirs. Mughal architecture was also deeply influenced by Hindu and vice-versa. Lack of a political power centre for Hinduism triggered shift of focus in Vaishnavism away from warrior aspects of Vishnu to that of a passionate forest god, the playful, amorous Krishna. Tulasidas tackled the problem of Rama’s treatment of Sita by inventing or incorporating the tradition of shadow- Sita (was this influenced by the Greek myth of shadow-Helen?). It is important, however, to not that Rama never tests Sita. He merely goads the shadow into the fire to bring back the real Sita.

Some gems of insights are provided by Doniger: Mirza Aziz Koka, foster brother of Akabr, recommended four wives, “a woman from Khurasan for housework; a Persian to converse with; a Hindu to raise children; one from Transoxiana to be beaten as a warning to others.” The myth of weavers’ thumbs being cut off by the British may grow out of the Ekalavya myth. The Nath temple in Gorakhpur has a board stating that Mohammad was a Nath yogi and Mecca was a Shaiva centre known as “Makheshvara” (lord of sacrifice). Is it not a blessing that no riots have occurred over this so far!

Very correctly Doniger notes that colonised people take on the mask that the coloniser creates, mimicking the coloniser’s perception of the colonized. Swallowing the Protestant line, Hindus rejected the aspects the British scorned and developed new forms like Arya Samaj, Brahmo Samaj—a new class brown in colour, white in thought and in taste, i.e. coconuts.

A rare gem is the discussion on Kipling’s “Kim” and of horses in it and in Rajput legends. Horses—Marwari with uniquely curved ears—provide the link with the West, as they became American movie stars and now live in Chappaquiddick.

She also surveys the Devi movement among Gujrat adivasis who spoke through women, making men shift to tea from liquor, breaking the economic bondage to Parsis who collected toddy and forced adivasi women into prostitution for touring officials. Devi took the place of intellectuals who in other places came in from outside to foment rebellion. This was an entirely tribal movement in which a deified form of Gandhi replaced the goddess for a while.

On page 639 Doniger claims that Vivekananda advised people to eat beef without citing any reference.

Coming to Hinduism abroad, in a TIME-magazine style survey of god-men-and-women, and ISKCON Doniger finds a major conflict between Hindu and non-Hindu constructions of Hinduism in the USA. This operates along the same fault line typical of Hinduism: worldly vs. non-worldly religion, reduced to Californification of Tantra vs. Vedanta. Americans embrace the erotic and violent aspects features of Kali and Tantra that Hindu tradition has tried to domesticate or censor. This is because NRIs are caught up in identity politics. Themes of Madhubani paintings are being altered according to what will sell in USA, also painting poor women being exploited. But what about the practices of the large Hindu population in USA? The rediscovery of Hinduism for the 20th century and its profound impact in India and abroad through Tagore, Sri Aurobindo and Gandhi are not covered, nor the variations in Bali, Mauritius, Trinidad, Fiji, South Africa.

Inadequate editing shows up in mismatches between notes and bibliography, chronology and text. Besides, Tagore returned not the Nobel prize but his knighthood and mothers do name sons “Yudhishthira” and even “Duryodhana” today in Orissa.

Doniger warns against the abuse of history which can be used to argue for almost any position in modern India. There is the political use of the Ramayana myth and the location of Lanka. She stresses the need for sensitive issue of the many Ramayanas, some of which are radically subversive. In an excellent conclusion, Doniger states that tension between various Hinduisms have enhanced the tradition and also led to incalculable suffering. Have we lost the ability to know our past objectively? Where has the plurality and the tolerance evaporated for which Hinduism was renowned? Modern “Hindus” appear to be imitating other fundamentalist groups in spouting hatred and intolerance against anything that reveals the multifarious aspects of Hinduism. Doniger’s presentation is an excellent supplement to Julius Lipner’s text-book style Hindus—their religious beliefs and practices.

15-Feb-2014

More by : Dr. Pradip Bhattacharya

|

Apropos Vinita Agrawal's query about limited immortality of gods, the puranic concept is of multiple cycles of creation, each with its own set of gods. Further, if humans do not perform yagyas, the gods lose power and fade away, which is why the asuras always disrupt the sacrifices. Gods also fall from heaven on account of egotism and sin, such as Indra murdering Vritra, Vala, Trishira, seducing Ahalya etc. |

|

Could understand Wendy better than this review! She deserves credit for that, although the book can't be endorsed under any circumstances. |

|

Very impressive review! I marvel at the depth of your own knowledge to delve deep into the issues raised by this book and offer pithy perspectives, arguments and counter arguments and sometimes even convincing validation of the texts, which the author might herself have lacked. A must read review...there's so much to absorb in it that I will have to come back here and read this many times over. You mentioned the Hindu concept of immortality at one place in the review...that even God's have a limited life. Please expand more on your views of the Hindu concept of immortality. I would love to know more! Thanks for this awesome, timely review! |

|

"An individual may regard himself as a fused hybrid: fully Muslim in some ways and fully Hindu in others (…)." Was Mirza Ghalib, the poet and "mango connoisseur", one of those hybrids, and only half-joking when he was arrested and explained at the police station that he was only half a Muslim since he drank ethanol but he never ate pork? |