Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

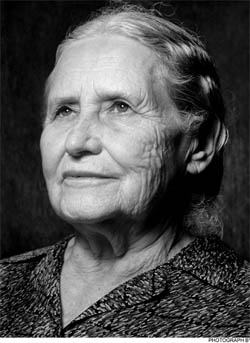

British writer Doris Lessing was this month named winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature - making her only the 11th woman laureate in the award's 106-year history. Announcing its choice to a huge cheer, the Stockholm-based Nobel Foundation described her as "that epicist of the female experience, who with skepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny".

British writer Doris Lessing was this month named winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature - making her only the 11th woman laureate in the award's 106-year history. Announcing its choice to a huge cheer, the Stockholm-based Nobel Foundation described her as "that epicist of the female experience, who with skepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny".

Lessing's initial reaction was characteristically non-conformist. "Oh Christ!" she erupted to a group of reporters camped on her doorstep in north London after they gave her the news when she returned from a trip to hospital because her son is ill. Lessing was entitled to exclaim. As the oldest winner of the literature prize - she will be 88 on October 22 - she had been short-listed for years, but had been informed in the past that the Nobel Foundation did not favor her.

Gossip in the cafes and bars of Stockholm had been that US writer Philip Roth might be this year's winner. In an interview with the Nobel Foundation after it finally acknowledged her worth, Lessing suggested the body might have struggled with the difficulty of categorizing her work, which spans the gamut from science fiction to Sufi mysticism to feminism.

Lessing herself rejects such categories. She has lived her life as a strong- minded, independent woman, but she takes issue with the feminist tag that many have been so keen to give her. "Of course I am a feminist. It goes without saying, it seems to me, but when you have said someone is a feminist, you haven't said very much," she said in a BBC interview with fellow writer Susan Hill.

She is obsessively interested in the female consciousness and in gender, as well as social divides, but her heroines' primary pursuit is of individual freedom. They are not about what she would consider over-simplistic generalizations concerning men and women. She generated a storm of controversy at the Edinburgh book festival in Scotland in 2001 when she implied the promotion of women had gone too far. "I find myself increasingly shocked at the unthinking and automatic rubbishing of men, which is now so part of our culture that it is hardly even noticed," she told the audience. "We have many wonderful, clever, powerful women everywhere, but what is happening to men?" she asked, "Why did this have to be at the cost of men?"

The novel that above all others won her a reputation as a feminist was 'The Golden Notebook'. Published in 1962, it tells the story of Anna Wulf, who aspires to live with the freedom of a man. She is a writer, who keeps different colored notebooks and tries to bring the threads of all of them together in one golden notebook. The famed author has acknowledged this form-breaking book tackles "certain ways of women's thinking" that were not previously in literature, but thinks their novelty value distracted readers from other aspects of the work.

"When I wrote 'The Golden Notebook', it never crossed my mind that I was writing anything particular about women. I was simply writing as a woman, out of experiences and discussions as a woman," she said. While the book has attracted a huge female following, Lessing has said many men have also written to her about it and she agrees with them that it is not just a book for women. Neither does she think it is as new and daring as it might seem. "The 1960s did not originate women's lib," said Lessing, who before then had belonged to communist, neo-communist and socialist movements where women's issues were constantly discussed.

"'The Golden Notebook' didn't come out of a vacuum, it came out of decades of talking about the situation of women and that goes back to the French Revolution," she said in her interview with Hill. Lessing's own character was formed as she took issue with stifling colonial society. She was born in what is now Iran in 1919 to British parents who later moved the family to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

The young Doris was sent to a convent school and then to a girl's high school in Salisbury, now Harare. She swiftly dropped out and left home at the age of 15 to continue her education herself through voracious reading. At 19, she was married and had two children; but feeling imprisoned, she abandoned the family. She went on to join the socialist Left Book Club, where she met and married Gottfried Lessing with whom she had one son. In 1949, unable to stand what she has described as "stultifying" colonial society, she left her second husband and set off to London with her son.

Looking back on her early life, Lessing was always trying to escape from narrow conformity and expectations of how women of a certain class ought to live their lives. She rejected the idea that women should give up their lives to marriage and children, saying, "There is a whole generation of women and it was as if their lives came to a stop when they had children."

It is a feminist sentiment, but for Lessing it is part of a wider rebellion. "Obviously it was very painful, but I could not stand that society. You have no idea of the awfulness of it, I was going completely mad and I wouldn't have stuck it so I knew I had to leave," she has said of her flight from Zimbabwe.

Ironically, with her Nobel Prize, she has finally become part of the establishment. As Britain's 'Guardian' newspaper put it, "A dissonant voice, an unclubbable writer, has just joined literature's most elite club."

28-Oct-2007

More by : Barbara Lewis