Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

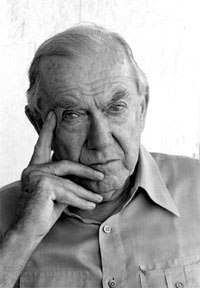

Graham Greene never won the Nobel Prize for literature,

a paradox; but, his tour de force lives on…

Graham Greene, in more ways than one, embodied his own allegory — with a velvety feel. If his novels were replete with tact for reality, and outspokenness, his literary humanism was just as riveting and wholesome. Greene carried “agony” with him, yes. However, his prose was uniformly sensitive — like newspaper headlines.

Graham Greene, in more ways than one, embodied his own allegory — with a velvety feel. If his novels were replete with tact for reality, and outspokenness, his literary humanism was just as riveting and wholesome. Greene carried “agony” with him, yes. However, his prose was uniformly sensitive — like newspaper headlines.

A hugely topical writer, Greene also grappled with everything that touched the human element — depression, capitalist monopolies, conflict, survival on the edge of the precipice, smuggling, spying, and anti-Americanism. A moralist and, therefore, controversial, Greene’s clearly-worded works of suspenseful, or ethical, ambivalence bordered on a delicate balance — of both gloom and salvation.

What’s more, Greene often indulged in self-deception, drawing upon the ground swell of his existentialistic mission — of sin, mental darkness, human mind, and failures — wherefrom he waited for everything to unfold with transcendent expectancy and perceptivity. He recognized the presence of armed combat, or war, too — as something to be put up with, like a certain continual, but not terminal, disease. And, if evil, to him, was like ague in his veins, he carried in his every expression an innate sense of political divergence.

Greene was very special. He carried the torch of English literature with him — like a colossus — with both power and grace, aside from a parabolic intent. As he once wrote: “The creative writer perceives the world once and for all in childhood and adolescence, and his whole career is an effort to illustrate his private world in terms of a great public world we all share.” Think of a Freudian metaphor — and, Greene echoed its striking nuance.

Greene not only explored the distinction between rituals and legalities, but also faith, candor and justice. That’s not all. Greene was a subversive romantic. But, what made him stand apart from other writers — in a league of his own — was his characteristic individuality. Greene never experimented with language, sabotaged conventional sequence of events, or favored glamorous themes. He effortlessly used his mind’s eye as his own radar and compass — a guided abstraction. In so doing, he typified the drama of the human soul.

The least parochial of writers, Greene was, in a sense, elusive. All the same, he left behind him a monumental wealth of writing, all witness to his literary genius. To cull an accolade: “The Greene novel seems to be based on a theory, which is not unlike the principle of aerodynamics according to which the aircraft must maintain a specific speed, or else it will tumble down. This speed Greene achieved by his masterly selection of detail, splendid economy of words, and by swift and frequent change of scenes.”

Although his background was typically British, Greene always defended popular movements struggling for freedom and democracy. And, while it would not be fair to justify that he was unaware of the pitfalls, for example, of one certain Fidel Castro, whom he always admired, Greene’s faith in the unconventional politician was derived from his deeply-held convictions that were visible as early as the beginning of the 1940s — in his book, The Lawless Roads.

Be that as it may, Greene critically X-rayed his own tradition and practiced his own art of morality — of not being at home in one’s own home. He could, of course, do without the Nobel Prize against his name — because, he was a kid at heart. It was Nobel’s loss; not his.

A descendant of R L Stevenson, the imperishable creator of Treasure Island, Greene’s canvas extended far beyond his novels. He also wrote a number of essays, short stories, and film scripts. He penned many books for children, too. His novel, The Man Within, published in 1929, was his first big success. What followed, thereafter, was extraordinary — Heart of the Matter, Power and the Glory, The Third Man, The End of the Affair, The Quiet American, Our Man in Havana, A Burnt-Out Case, The Human Factor, The Tenth Man etc., including several other innumerable, or “lesser,” writings.

Having been responsible for hastening one of India’s finest writers, R K Narayan’s entry into the world of books, as a novelist in his own “write” and right, by some years, Greene also had a penchant for adventure, in the dangerous light of things. No small wonder, that, his dream from childhood was focused to playing the Russian roulette. Needless to say, Greene, the writer, was just as fearless. Yet, what was most vital to him was the human act, its morality — of individuals as well as nations. His human axiom, therefore, speaks to us directly, in effect, of our own experiences and observations — oppression, politics, belief and trust. Besides this, Greene’s classicist (“Catholic”) outlook was quite autobiographical — universal, and lush Green(e), forever. Writers like him are never lost or forgotten.

By his own admission, Greene wrote both “entertainment” and “serious novels” — many of them with the underpinning of a politically enthralling register. What, of course, made Greene Greene was his sublime affinity for words, and brevity of expression. Also — if the secretiveness, in his novels, is seductive, so is sin. It’s alluring. A number of Greene’s heroes, like Scobie, believe themselves to be disaster-prone; and, they also seek their “destiny” with a kind of rapture. Another paradigm: the murderer Pickie, in Brighton Rock, is more sympathetic than the righteous avenger Ida. All the same, some of Greene’s foremost critics, in expression and idiom, insist that Greene spoke of immorality, or sin, only in his books, and that he was in real life “immoral.”

It is, therefore, not without reason, thanks to constant change in our inconstant world, that many critics today consider Greene as “vain, duplicitous, and out-of-date.” This is not all. Some of Greene’s more profound critics have also castigated him, and pushed him down from his high pedestal into discredit. However this maybe, what makes Greene expansively alive in his works is his worldliness — a linguistic trait that continues to be a model for the practicing writer.

Interestingly, It is also quite ungrudgingly accepted that Greene’s moral indistinctness serves us better now than George Orwell's transparency, albeit modern reviewers of his works suggest that Greene can be regarded as our greatest novelist, during his time, the master of ingenuity and excitement — a writer whose ambivalent moral equations and compromised characters invaded the consciousness of two generations of readers. This, in spite of our ever-changing world having moved on to another century and other manners of thought and belief.

Greene, with his own sense of practical wisdom, perforce, saw it all coming. As he once wrote: “To render the highest justice (to corruption), you must retain your innocence… You have to be conscious all the time within yourself of treachery… to something valuable.”

Call it “psychical” insight, or what you may, Greene, and his novels, espouse an ambivalent play between luminosity and murky shades of faithfulness and failure, innocence and seediness, hope and despair, romance and realism. In other words, they present us a remarkable tapestry, quite unlike any other writer’s — born or unborn.

Post Script:

A Virtuoso In His Own “Write”

Graham Greene was a writer like no other. His reminiscences were anecdote-free. He talked of smells and sights — of human distress and inquiries of trust. Few writers, today, deal in grey shades, or hues.

A great admirer of Somerset Maugham, Greene did not magnify sarcasm and spoof; nor did he amplify motives. In today’s world, publicity-stunts and the bizarre grab attention, yes. Not down-to-earth, mesmeric story-telling ability, which was Greene’s hallmark. Yet, it’s going to come back — sooner than later.

Observes Haresh Pandya, an academic, writer, and avid Greene reader: “What gave Greene’s landscape a highly distinctive quality and, above all, a deep understanding of the human mind was his brilliant narrative — a technique marked by a lucid style and choice of ‘spotted’ locations. It’s a characteristic that also distinguishes him from many other eminent novelists and short-story writers — both past and present.”

Adds Pandya: “Few can, in fact, match Greene when it comes to exploration of emotions — like guilt, frustration and self-pity. Greene’s preoccupation with moral dilemmas (personal, political, and religious), may have had something to do with his own sense of Catholicism — one that counteracts the misery in his novels (by implications of spiritual dignity, and even nirvana), in the face of suffering and/or distress.”

Says Lakshmi Subramaniam, a long-time Greene fan: “I find Greene quite easy-to-read. What I find most appealing in his novels is the way he engages us in everyday details; simple details that make us feel just like human beings. Greene also does not bother his readers and others with complex data, or ‘records.’ He reports like the good old newspaper writer (so, it is ‘trouble-free’ for almost all of us to relate to him). This is something that is missing… in our newspapers, or magazines, and also in books and writers, today.”

01-Jan-2006

More by : Rajgopal Nidamboor