Feb 05, 2026

Feb 05, 2026

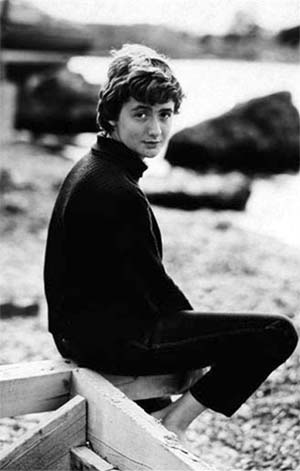

In 1954 at the age of 18, French writer Francoise Sagan became a sensation for her ground-breaking novel 'Bonjour Tristesse' ('Hello Sadness'), an almost hypnotic tale of a wayward teenager who meddles in her libertine father's affairs as she awakes to her own sexuality. More than half a century later and fashionable as ever, Sagan has been hailed by the French press as essential reading for the summer of 2008.

In 1954 at the age of 18, French writer Francoise Sagan became a sensation for her ground-breaking novel 'Bonjour Tristesse' ('Hello Sadness'), an almost hypnotic tale of a wayward teenager who meddles in her libertine father's affairs as she awakes to her own sexuality. More than half a century later and fashionable as ever, Sagan has been hailed by the French press as essential reading for the summer of 2008.

The current interest has been whipped up by a film "Sagan" - released on June 11 in France - as well as the reprinting of some of her numerous works and the publication of biographies, including one by her female lover Annick Geille entitled 'Un Amour de Sagan' ('A Love of Sagan').

For Geille, Sagan's appeal endures because she was prescient. "Artists by definition are visionaries: they are able to grasp phenomena their contemporaries cannot see. Francoise Sagan lived in her era, while at the same time foreseeing the next one," she said.

"This dual ability to understand the superficiality of certain edicts and to imagine an alternative, especially regarding anything concerning behavior, such as sexuality or homophobia ... made Sagan someone 30 years ahead of her time."

Back in 1954, 'Bonjour Tristesse' was regarded as scandalous, but that only added to its appeal, making it an instant bestseller and helping to launch its author into the kind of reckless, dashing life-style classically associated with men not women. She drove fast cars, drank, overdosed on drugs, racked up debts, fell foul of the tax authorities and took lovers of both sexes.

While they did not necessarily approve of all that she did, feminists were impressed by her defiance of a patriarchal society and some of them have sought to claim her for their cause, but Sagan did not want to be contained by the strictures of any category.

"She distrusted feminists and all forms of militancy," said Geille. "In the literary context, Francoise Sagan hated 'feminist literature', she thought there was literature, either good or bad regardless of the sex of the author. ... she believed in the intrinsic qualities of human beings beyond the sex barrier."

If her freedoms made Sagan a very modern woman, her appeal now, four years after her death at the age of 69, is partly based on France's yearning for a Bohemianism it associates more with the past than the present.

"The French, it seems, are greatly nostalgic, not only for the literary glory they used to enjoy but also for the sexual freedom represented by Sagan," wrote Matthew Campbell in Britain's 'The Times' newspaper.

It's not that the French have become prudish, but research made public earlier this year suggested that as women increase their power in the workplace, both sexes suffer from the kind of sexual anxiety they might imagine Sagan eschewed when she scoffed at conventional coupledom and experimented with love triangles.

The major piece of research published in respected French magazine 'Le Nouvel Observateur' concluded confusion was rife. Women were taking the sexual initiative more than in the past, but that did not mean they were liberated.

Nathalie Bajos, one of the leaders of the study instigated by France's national AIDS research agency, said sexual life tended to replicate the inequalities of social life.

"There is a big division in that for women sex is linked with emotions and for men it is linked with need," she said.

Sagan transcended all that. When asked by Geille if she believed in love, she is said to have replied: "I believe in passion. Nothing else."

Geille's biography, published late last year by Pauvert, has been lauded, not just because it taps into a fascination with a woman who lived beyond the constraints, moral or otherwise, that bind most of us, but also for its own merits.

French weekly magazine 'Paris Match' said the book was of high literary value. "In the hands of a more thankless stylist, the material would have fallen into vulgarity or sensation."

Sagan's own work is considered uneven. 'Bonjour Tristesse', which she wrote in a rapid burst of inspiration, remains her most acclaimed and most famous work and has been translated into many languages.

It prompted one of France's most respected novelists, Francois Mauriac, to hail the talent of "this charming little monster".

While other Sagan novels were also bestsellers, much of her work was unremarkable.

"Though she continued to produce novels and plays at a rate of roughly one a year, Francoise Sagan's writing lost its astringency and she began to be dismissed as a lightweight author of women's romantic fiction - more Mills and Boon than enfant terrible," Britain's 'Telegraph' newspaper had commented in an obituary.

Tributes in France at the time of her death focused instead on what she had achieved and arguably would have achieved even if she had put down her pen after her first novel.

"With finesse, emotion and subtlety, Francoise Sagan explored the spirit and passions of the human heart," the then French President Jacques Chirac said in a statement. He described her as "a leading figure in her generation", who helped to raise the status of women in France. From a man that was praise indeed and implied she had been forgiven for the freedoms and sexual frankness that in previous generations only men were allowed.

06-Jul-2008

More by : Barbara Lewis