Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

In Mauritius, we made friends with a bead seller on the beaches of Mont Choisy, who introduced himself as 'Moootooosaaamy'. He must have seen our surprise for he laughingly told us that he was fourth generation Tamil, who doesn't know the language at all and not interested in finding out about his ancestors, original culture or roots. 'I'm a cocktail' he said, when I curiously questioned him, 'mix of Tamil, African, French, Cr'ole, don't know what else'. But what really captivated me was the way he pronounced his name - a typical Tamil name, that you can come across anywhere in the south. I asked him about it. He said, 'Yes, that's Moo'tooo-saamie' ' dragging out each syllable musically. Was it because of the accent, I wondered, or was it an attempt by one of his ancestors to wash over the past? I was interested enough to find out.

Today's Mauritius has an identity of its own, there is such a great mix of cultures and gene lines there, that it is quite impossible to tell where a person originally came from. Immigrant laborers, I also know, have been the pillars on which modernity was built in two nations ' one Mauritius, the other Singapore. Mootoosamy was merely a push in the right direction and my hunt for a bit of history took me to the sugarcane fields of central Mauritius and the alleyways of her capital Port Louis.

Today's Mauritius has an identity of its own, there is such a great mix of cultures and gene lines there, that it is quite impossible to tell where a person originally came from. Immigrant laborers, I also know, have been the pillars on which modernity was built in two nations ' one Mauritius, the other Singapore. Mootoosamy was merely a push in the right direction and my hunt for a bit of history took me to the sugarcane fields of central Mauritius and the alleyways of her capital Port Louis.

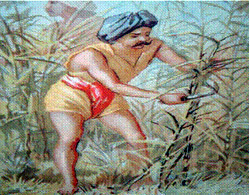

It was only after I visited Beau Plan and its innovative exhibition 'l'Aventure du Sucre', that I found the origins of that pleasing sounding Tamil name. I've seen various efforts to keep alive a place's history; but Beau Plan was something of a novelty - an old sugar factory, built by the colonials in the mid-eighteenth century, converted into an interactive museum with displays relating to Mauritian history and economic development. The nicest part was that it hadn't lost the spirit of what it was originally built for. The old machinery, all polished to a shine, was subtly woven in along with the other exhibits, while the steam engines and railway parts used are nicely displayed in the garden outside. This exhibit showed the visitor exactly how sugar is manufactured, starting with the harvest of the sugarcane, to the processing of the different kinds of sugars, right up to packing and dispatch -a little engine loaded with sugar sacks was chugging around a little track at one end.

It was only after I visited Beau Plan and its innovative exhibition 'l'Aventure du Sucre', that I found the origins of that pleasing sounding Tamil name. I've seen various efforts to keep alive a place's history; but Beau Plan was something of a novelty - an old sugar factory, built by the colonials in the mid-eighteenth century, converted into an interactive museum with displays relating to Mauritian history and economic development. The nicest part was that it hadn't lost the spirit of what it was originally built for. The old machinery, all polished to a shine, was subtly woven in along with the other exhibits, while the steam engines and railway parts used are nicely displayed in the garden outside. This exhibit showed the visitor exactly how sugar is manufactured, starting with the harvest of the sugarcane, to the processing of the different kinds of sugars, right up to packing and dispatch -a little engine loaded with sugar sacks was chugging around a little track at one end.

Sugarcane farming and sugar-making has always been the mainstay of Mauritian economy, then and now, from the time its cultivation was introduced by the Dutch in the seventeenth century. Beau Plan was just the right place to get a glimpse into that and the contribution of Indian migrants to make it what it is today. Surrounded by cane fields and located around the corner from the famed Pamplemousses Garden, the factory opened up a whole new peek into the country's past and the actual facts surrounding the mass movement of Indians to a far-off land, among the first of its kind to happen anywhere in the world.

Sugarcane farming and sugar-making has always been the mainstay of Mauritian economy, then and now, from the time its cultivation was introduced by the Dutch in the seventeenth century. Beau Plan was just the right place to get a glimpse into that and the contribution of Indian migrants to make it what it is today. Surrounded by cane fields and located around the corner from the famed Pamplemousses Garden, the factory opened up a whole new peek into the country's past and the actual facts surrounding the mass movement of Indians to a far-off land, among the first of its kind to happen anywhere in the world.

The old chimney was almost crumpling to pieces, but still standing, thankfully, due to good maintenance. The chimneys in all these factories were the social glue, holding all the immigrants together. Just like the temple, or a banyan tree, is a gathering place in any little village, the chimneys were where the coolies would assemble when not working to keep in touch with themselves and reality.

Old photographs, registers, and other objects, perfectly displayed, show how the coolie system came to be. This was the time the mighty British were consolidating their empire throughout the world. They had just taken over from the French, settling down on the island with ideal settings for sugarcane farming, relying on resident African slaves for labor. When slavery was abolished in 1835, most freed slaves refused to continue work, preferring to go their own way. To the masterly British, quite unused to menial work, coolies were the only answer. Of course, as they did always, they looked toward India for a solution to their labor problems.

Old photographs, registers, and other objects, perfectly displayed, show how the coolie system came to be. This was the time the mighty British were consolidating their empire throughout the world. They had just taken over from the French, settling down on the island with ideal settings for sugarcane farming, relying on resident African slaves for labor. When slavery was abolished in 1835, most freed slaves refused to continue work, preferring to go their own way. To the masterly British, quite unused to menial work, coolies were the only answer. Of course, as they did always, they looked toward India for a solution to their labor problems.

Staring in 1829 and by 1850, some 500,000 lower-class people from India, (the majority of them from Madras, some from Bihar, Gujarat, and Bombay), had migrated to Mauritius. Fleeing miserable conditions back home; giving up their deeply held religious beliefs against crossing the deep ocean, they came by the millions to start a new life, only to find it would be no better here.

They became the backbone of the country; their tedious work contributed so much to its development that sugarcane cultivation itself came to depend wholly upon them. Landing in the port, they were separated and sent to the various factories where they were housed in little shacks. Villages and townships for them came along much later.

It was in one of those registers that I noticed my 'cocktail' friend's name. On arrival at the port, colonial bosses registered each person's name on book, after which a copy was inserted into a copper cylinder and hung around their necks ' rather like tagging a pet. These writers apparently, on hearing such outlandish south Indian names as Muthusamy and Kumarasamy, wrote it down the way they themselves pronounced it ' 'Moo-too-saamie'. Looking down at the list, I was swept back in time. I could easily picture a long queue of coolies snaking down the pier, the scratch of the quill pen, as the man painfully and distastefully pronounced each syllable he wrote down ' 'Mooo' pause 'tooo' pause 'saamie', 'Next!' Then it would have been 'Coo-maara-saamie'. So on, so forth.

At Churchill Street in Port Louis, we came across a relatively unknown, non-touristy place that impressed me no end. The much ignored L' Muse' de la Photographic has a staggering display of a million photographs taken over the last 160 years, with as many old negatives. The owners of this private museum are obviously very passionate about preserving the island's history. Here was the perfect place where I could find more such poignant images, and I was not disappointed.

The pictures are moving, some startling. Worn, wrinkled faces, with name-cylinders around their arms or necks, peeped out of each, a mixture of despair and hope reflected in their wise, seen-everything eyes. Faces that had already seen a whole lot of hardship in their native country, faces leaving behind everything they knew to carve out a living in a distant land across the ocean, faces full of hope about the new life they were starting out on, faces that thought they would have a better life in this strange place; that thought they could give a better life to their children - faces that a whole nation then came to depend upon.

05-Nov-2006

More by : Naiya Sivaraj