Feb 05, 2026

Feb 05, 2026

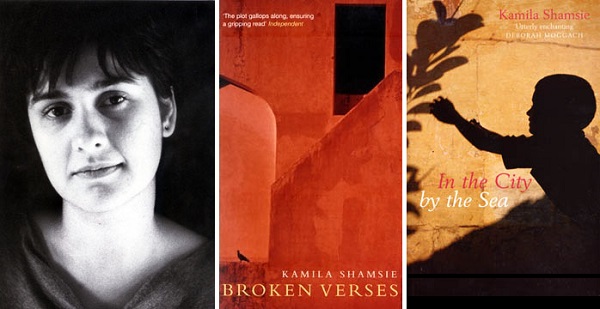

Writer Kamila Shamsie, 33, is one of Pakistan's most promising literary talents. First published at the age of 25, she now has four highly acclaimed books to her credit. She also received the Prime Minister's Award for Literature in Pakistan in 1999.

Kamila's four published novels - 'In the City by the Sea' (1998), 'Salt and Saffron' (2000), 'Kartography' (2002), and 'Broken Verses' (2005) - were written back to back, and each novel has spilled over into the other. She was still in grad school when she was revising the first, writing the second, and had already written the short story that grew into 'Kartography'. As she worked on one novel, she would think that an idea could be worked on more. That would turn into the next novel. 'Broken Verses' coincided with 9/11, and US publishers didn't want to buy it.

Kamila's favorite rejection line is: "It doesn't have enough culture in it."

Visiting Delhi a few weeks ago, Kamila took time out to talk about her writing, the politics of representation and authenticity.

After 'Broken Verses', Kamila took a break of three or four months. The break, she recalls, stretched into 18 months, during which she deliberately emptied her mind of thoughts about novels because, she says, the novel exhausted her. She had also fallen into habits of writing - for example, "this generational thing". In each of her novels, a younger generation figures out the secrets of the older one, but this was really a solution to a technical problem - a novel requires conflict, a secret is a good way to do it.

This 18-month long break has resulted in a new novel, whose first draft, "with luck", should be ready in two months. When it will be published depends on the re-writes - 'Broken Verses' was rewritten six times!

The new novel is different to the earlier ones in many ways. So far Kamila's novels have been set in her hometown Karachi. She spends time in London, where she writes, and sometimes teaches at Hamilton College in upstate New York, but Karachi is her base.

This fifth book is only partly set in Karachi; and, unlike the first four, it is a linear story. It is in four parts - Karachi in 1945, New Delhi in 1947, the Pakistan-Afghanistan border in 1982, and New York and Afghanistan in 2002. Why Afghanistan? "Because after 2001-2002, you cannot talk about New York without talking about Afghanistan." The time the book covers means that there are bound to be two generations.

There's overlapping, parallelism and intersecting but the older generation is not shown through the discoveries of the younger one. Each generation is itself; each gets its due. Three of Kamila's novels began as short stories. So, does the new novel have a similar genesis? No, she says. Earlier, she had been thinking deficiently about the short story. If she became very involved in it, the story would transform into a novel. However, now there is no overlap for her between the short story and the novel. The stories on which 'In the City...', and 'Salt and Saffron' were based worked well as short stories, but the 'Kartography' one was different, she says.

She likes the short story as there is no excess in it, no fat, every word counts. It has an intensity throughout, which you cannot have in a novel, "not in my novels anyway." A novel can only have patches of intensity. The short story allows you to drop an image delicately on page one and pick it up on the last page. It is OK to expect readers to make the connection - you can't do that in the novel.

In some ways short stories are more difficult to read. Like poetry? "Yes," she says. She reads a lot of poetry and was deeply influenced by her teacher, poet Agha Shahid Ali. She admires the short story form, but loves prose fiction as well because it "allows you to do so much more with interior and exterior, with thinking and seeing. You can show what is going on in a person's mind, you can describe what she is looking at, you can show how her glance at a part of the Qutub Minar - and the thought she has - can tell you what's going on in her marriage."

Does Kamila think that someone who writes sustained long works, like serious novels or epic poems, is superior to one who, perhaps, writes only short stories? "No," she says. "I have told myself, 'I'm not crossing 399 pages.' The published novel may be 450 pages but not my manuscript. I have no respect for sprawl." Her last draft is longer than the first, she laughs, but she admires the pared-down novel. The more it is pared down, the better it is. Does she like showing her work to others? She finds it useful to be told 'this works, that doesn't,' but she shows her work in progress only to her old friend Elizabeth (who tells her what doesn't work) and writer Aamer Hussein (who tells her what does) before sending it to her agent.

Since she spends half her time out of Pakistan, what are Kamila's views on the expat vs. resident writer question? "Authenticity," she says, "is fraught with problems. We come from a part of the world that has been written about inaccurately for a very long time, and we need to correct that. But a novel must follow its own internal rules set by the writer. The novel creates an illusion and readers don't want that to be broken."

Obviously, there are political angles to authenticity. There's the politics of representation. Kamila comments, "Stereotypes are real problems, and we must confront them. But is it possible to be authentic? You can live in Delhi and not know Delhi, while going away from it may make you obsessive about it in a certain way. You may be able to write about that and it would be authentic. But for a novelist, sometimes authenticity is simply not possible."

In Kamila's new novel, there is a section about pre-bomb Nagasaki. "I cannot go back to that [era]. Any novel set in the past destroys questions of authenticity because you haven't been in the past."

By arrangement with WFS

14-Apr-2007

More by : Shobhana Bhattacharji