Feb 05, 2026

Feb 05, 2026

Analyzing the contribution of women artists to modern art in Pakistan is not simply a matter of inserting them into the existing history of contemporary art. More an acknowledgement of the atypical, such an analysis pries open questions of containment, denial, resistance, and celebration. It can be argued, of course, that the gender 'difference' is only one of many that shape art-making in a society, but it is the configuration of the 'difference' that has been crucial to the work produced, and accords it an unusual significance in Pakistan.

Analyzing the contribution of women artists to modern art in Pakistan is not simply a matter of inserting them into the existing history of contemporary art. More an acknowledgement of the atypical, such an analysis pries open questions of containment, denial, resistance, and celebration. It can be argued, of course, that the gender 'difference' is only one of many that shape art-making in a society, but it is the configuration of the 'difference' that has been crucial to the work produced, and accords it an unusual significance in Pakistan.

The first decade of Pakistan's existence was fraught with political and social upheavals. The role played by women in the struggle for Independence and the Muslim League's movement for the formation of Pakistan was important, and occasionally crucial. This was especially true in urban areas where women's votes made a substantive difference in the 1946 elections, resulting in a resounding success for the Muslim League.

However, Muslim women casting their votes, presented and encouraged as a religious duty, held serious implications for them in the future state of Pakistan. The enlightened leaders of the Muslim League could not have foreseen the political strategies leading to orthodox interpretations of the ideology of the state.

However, Muslim women casting their votes, presented and encouraged as a religious duty, held serious implications for them in the future state of Pakistan. The enlightened leaders of the Muslim League could not have foreseen the political strategies leading to orthodox interpretations of the ideology of the state.

The Fine Arts Department at the Punjab University in Lahore, headed by Anna Molka Ahmed (1917-1994), was set up in 1940 and admitted only female students at the time of its inception. The rationale, according to the then Vice-Chancellor, was to discourage women from 'cluttering up the important departments like chemistry and physics.'

The Vice-Chancellor of the Punjab University was only articulating the common assumption about the objectives of fine art teaching, i.e. to train women to be 'artistic', not 'artists'. Art education would 'enhance the natural proclivities of women', making them better 'home decorators', inculcating in them the finer sensibilities expected of mothers, wives, and daughters.

In this first phase after Independence, women art educators laid the foundation for the teaching of art all over Pakistan, in schools, colleges, and universities.

It was with the passage of time that what had begun as a safe educational pastime for middle-class women became a vehicle for communication and expression in the public domain, and paved the way for personal and cultural insurrection.

During the National Exhibition in Lahore, in 1983, women artists attending the inauguration met privately and drafted a manifesto for themselves. The two-page document was signed by fifteen women artists. Never made public due to the prevailing political circumstances, the preamble of the manifesto made its intentions clear:

We, the women artists of Pakistan, having noted with concern the decline in the status and condition of life of Pakistani women, and having noted the effects of the anti-reason, anti-arts environment on the quality of life in our homeland-

Having noted the significant contribution the pioneering women artists have made to the course of arts and art education in Pakistan.Believing as we do in the basic rights of all men, women and children to a life free from want and enriched by the joys of fruitful labor and cultural self-realization and our commitment, as practitioners and teachers of the arts, to the noblest ideals of a free, rational and civilized existence.

Affirm the following principles to guide us in our struggle for the cultural

development of our people to serve as the manifesto of the women artists of Pakistan.

There followed seven principles ~ which upheld the struggle for women's rights in the wider context of human rights and the movement for democratic freedoms. The document condemned the propagation of the obscurantist and discriminatory laws being enacted, and, by implication, it became a subversive tract.

For most of the women present, putting their signature to the manifesto was their first experience in articulating such views in a group, and the first step towards consciously connecting their art to a socio-political reality. They were not alone. Women poets and writers had already taken the lead. Kishwar Naheed and Fahmida Riaz consolidated the genre that became 'subversive poetry'.

Women artists cast around for new symbols that could serve their purpose. The regime's rhetoric provided recurring images. The 'protection of women' through the chador (veil) and chaar diwaari (four walls of the home) became the cornerstone of the state's agenda. The bid for ownership of the female body formed the premise of the Hudood Ordinance. This law, which did not differentiate between fornication and adultery, decreed death by stoning as punishment for adultery.

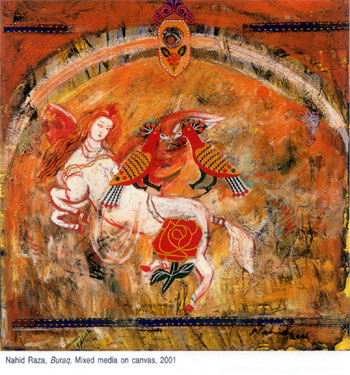

As a symbol of fecundity, the female body was a prime site for provocation, an abode of sin and forbidden sensations. For women artists, the female body, its containment, concealment, and visibility became a matter for meaningful exploration. A world away, feminist artists in the West were rejecting female nudes as one of the obvious repositories of male-dominated art canons. For the Pakistani woman artist, the uncovering of the female body became a rallying call to the barricades.

As the 1990s witnessed a succession of elected governments come and go in Pakistan, issues of patriarchy, sectarianism, and religious orthodoxy confronted civil society. Military paternalism continued; media and information technology surged into urban society, and artists found larger audiences and new patrons.

As women became more vocal, they confronted the male gaze and questioned labels. Man was being defied with the use of irony. Summaya Durrani's Faceless Nude series (1995) were tongue-in-cheek statements about women's bodies being served up to the male consumer as delectable morsels. An artist who culled her mixed media images and material references from myriad sources, Durrani's investigations were defined by her study of art history, printmaking techniques, and a personal take on philosophical structures.

(Extracted from "Memory, Metaphor, Mutations Contemporary Art of India and Pakistan" by Yashodhara Dalmia & Salima Hashmi. Oxford University Press, Price: Rs 2,950)

13-Jan-2007

More by : Salima Hashmi