Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

‘I hesitate not to pronounce the ‘Geeta’ a performance of great originality, of a sublimity of conception, of reasoning, and diction, almost unequalled, and a single exception, among all the known religions of mankind.’

– Warren Hastings in the Introduction to the First-ever English Translation of the Bhagavad Gita (4- 10- 1784)

Influenced by the marvelous writing and the magnificent oratorical skills of Edmund Burke, a champion of democracy and a hero to many literature students like me in our college days in the mid 1960s, Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of British India, had always been considered, erroneously as it proved later, as a stark villain, a person who deserved to be detested and abhorred for what Burke had described as his ‘high crimes and misdemeanors.’

‘I impeach Warren Hastings, Esquire, of high crimes and misdemeanors, ‘Burke had thundered in the Westminster Hall on 15th February 1788, ‘I impeach him in the name of the Commons of Great Britain in Parliament whose parliamentary trust he has betrayed,…… I impeach him in the name of the people of India whose laws, rights and liberties he has subverted, whose properties he has destroyed, whose country he has laid waste and desolate. ……….’

Burke’s eloquence, as also that of fellow literary man Richard Brinsley Sheridan, was such that the high and the mighty and the glamorous of London society were in full attendance throughout the trial in the historic hall of British Parliament, paying a hefty entrance fee. But in spite of Burke and all his venomous vehemence, Hastings was exonerated of all the charges by the court after a protracted seven year- long trial.

The only result of Burke’s failed impeachment bid was that it ruined Hastings financially and traumatized him emotionally. The financial reparation awarded by the impeachment court of a lifelong annual pension of 4,000 pounds sterling was hardly sufficient to wipe out the blot on his name cast by Burke and others.

Hastings, who as the first Governor General laid a solid foundation for British rule in India for the next two centuries through a combination of tact, administrative acumen, subterfuge and ruthlessness, may or may not deserve the kind of indictment foisted on him by Burke. But in one respect, the role he played in bringing out the first ever English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, the whole of India should ever be grateful to him.

This translation, by an East India Company official, Charles Wilkins, marked a watershed in the cultural history of India as it sparked translations of the Gita in various European languages and drew for it world-wide attention and acclaim.

It was by chance that I laid my hands on a new reprint of this historic volume while browsing through books in the recent arrival section of the Thiruvananthapuram Public Library. The book, for me, was an eye-opener, indeed a Book of Revelations.

Hastings might have had his own reasons, predominantly administrative, for thinking of bringing out an English version of a sacred book of the Hindus. In a lucid and lengthy letter to Nathaniel Smith, Chairman of the Court of Directors of The East India Company, a letter that later served as the Introduction to ‘The Bhagvat-Geeta’ that the Company published, Hastings explained the reasons he had in mind. Cultivation of language and science, he pointed out, was not only useful in forming the moral character and habits of service. ‘Every accumulation of knowledge, especially such as is obtained by social communication with people over whom we exercise a dominion founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state. It is the gain of humanity.’

He said in the specific instance that he had stated ‘it attracts and conciliates distant affections, it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjection and it imprints on the hearts of our own countrymen the sense and obligation of benevolence.’

He referred to the great prejudice the western world had about the natives of this country. ‘It is not very long since the inhabitants of India were considered by many as creatures scarce elevated above the degree of savage life. Nor, I fear, is that prejudice wholly eradicated, though surely abated. Every instance which brings their real character home to observation will impress us with a more generous sense of feeling for their natural rights. But such instances can only be obtained in their writings. And these will survive when British dominion in India shall have long ceased to exist, and when the sources which once yielded of wealth and power are lost to remembrance.’

In one of the most emphatic authentications of the worth of the book he was espousing, Hastings said ‘I hesitate not to pronounce the Geeta a performance of great originality, of a sublimity of conception, reasoning and diction, almost unequalled; and a single exception, among all the known religions of mankind’. He also said the theology it expounded was ‘accurately corresponding with that of the Christian dispensation, and most powerfully illustrating its fundamental doctrines.’

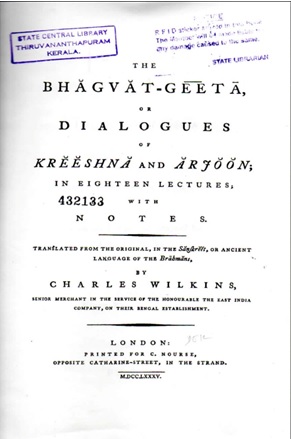

It was on the basis of his strong and persuasive plea that the East India Company brought out the book, ‘The Bhagvat Geeta or Dialogues of Kreeshna and Arjoon in eighteen Lectures, with Notes, Translated from the Original, in the Sanskreet, or ancient language of the Brahmans. By Charles Wilkins, Senior Merchant in the service of The Honourable The East India Company, on their Bengal Establishment.’ The book was printed in London, the press being C Nourse, in the Strand, in the year 1785.

Hastings had high praise for the translator, Charles Wilkins, a pioneer engraver who gave shape to Bengali typefaces. Shortly after joining the service of the East India Company he had acquired great proficiency in Persian and Bengali and had become the official translator of the Company. It was Hastings who sent him to Benares, ‘a place considered to be the first seminary of Hindoo learning,’ to learn Sanskrit. His mentor at Benares was a reputed Sanskrit scholar, Kalinatha Bhattacharya, under whose guidance he attempted a translation of Mahabharat. He could complete only `one third of the epic. The Bhagvat-Geeta he brought out formed part of the work he had completed.

Explaining the difficulties he had encountered in translating the Gita, Wilkins said ‘The Brahmans esteem this work to contain all the grand mysteries of their religion and so careful are they to conceal it from knowledge of those of a different persuasion and even the vulgar of their own, that the Translator might have fought in vain for assistance.’

One argument he put forward in his note was that the Gita was an attempt at promoting a sort of monotheist Unitarianism as against the polytheistic and idolatrous worship enshrined in the Vedas. ‘It seems as if the principal design of these dialogues was to unite all the prevailing modes of worship of those days, and, by setting up the doctrine of unity of Godhead in opposition to idolatrous sacrifices and the worship of images, to undermine the tenets inculcated by the Vedas.’ Although the author (of the Gita) dared not make a direct attack, either upon the prevailing prejudices of the people or the divine authority of those ancient books, yet, he seemed to offer eternal happiness to those who worship Brahm, the Almighty. As for others, who follow other Gods, it shall be but a temporary enjoyment of an inferior heaven, for a period measured by the extent of their virtues. His (Krishna’s) design was ‘to bring about the downfall of polytheism, or, at least to induce men to believe God present in every image before which they bent and the object of all their ceremonies and sacrifices.’

Pointing out that throughout the discourse Krishna mentions only three of the four Vedas, Wilkins said this was a very curious circumstance as the belief was that all the four Vedas, Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda and Atharva Veda, were promulgated by Brahma at the time of creation. ‘The proof then of there having been but three Vedas before his time is more than presumptive and as the fourth mentions the name of Kreeshna, it is equally proved that it is a posterior work.’

‘This observation,’ he pointed out, ‘has escaped all the commentators and was received with great astonishment by the Pundeet (Kalinath) who was consulted in the translation.’

About the style and quality of Wlkins’ translation Hastings had said that it was comparable to the most esteemed of the prose translations in European languages. ‘I should not fear to place, in opposition to the best French versions of the most admired passages of the Iliad or Odyssey or of the Ist and VIth Books of our own Milton, highly as I venerate the latter, the English translation of the Mahabharat.’

It will be interesting to juxtapose Wilkins’ treatment of certain passages from the Gita and popular translations by commentators like Swamy Tapasyananda (Sri Ramakrishna Mutt).

Dharmakeshethre kurukshethre…… (1.1)

‘Tell me, O Sanjaya, what the people of my own party and those of the Pandoos, who are assembled at Kurukshethra resolved for war, have been doing. (Wilkins)

O Sanjaya! What indeed did my people and the followers of the Pandavas do after having assembled in the holy land of Kurukshethra, eager to join battle? (Swamy Tapasyananda)

Yada yada hi dharmasya glanir bhavathi bharata… 4.7-8

As often as there is a decline of virtue and an insurrection of vice and injustice, I make myself evident; and thus I appear from age to age for the preservation of the just, the destruction of the wicked and the establishment of virtue. (Wilkins)

Whenever there is a decline of Dharma and ascendance of Adharma, then, O scion of the Bharata race, I manifest myself in a body. For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the evil and for the establishment of Dharma I am born from age to age. (Swamy Tapasyananda)

Janma karma cha me divyamevam yo vetti thathvatah ( 4. 9)

He, O Arjun, who from conviction acknowledgeth my divine birth and actions to be even so, doth not, upon quitting his mortal frame, enter into another, for he entereth into me. (Wilkins)

O Arjun! He who thus understands the truth about my embodiment and my deeds – he on abandoning his present body, is not reborn, he attains to Me. (Swamy Tapasyananda)

Divi surya sahasrasya bhaved yugapad utthitha (11.11)

The glory and amazing splendor of this mighty being may be likened to the sun rising at once into the heavens with a thousand times more than usual brightness. (Wilkins).

What brilliance there would have been if a thousand suns were to blaze forth all of a sudden in the sky – to that was comparable the splendour of the great Being. (Swamy Tapasyananda)

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst forth at once in the sky, that would be like the splendour of the Mighty One. (Quoted by J Robert Oppenheimer when he saw the blaze of the experimental atomic explosion at the New Mexico desert)

Kachchidetat chrutam partha tvayaikagrena chetasa…(18.72)

Hath what I have been speaking, O Arjuna, been heard with thy mind fixed to one point? Is the distraction of thought, which arose from thy ignorance, removed? (Wilkins)

Has this teaching been heard by you, O Arjuna, with a concentrated mind? Has all delusion born of ignorance been dispelled from you, O Dhananjaya? (Swamy Tapasyananda)

Yatra yogesawara krishno yatra partho dhanurdhara… (18.78)

Wherever Kreeshna the God of devotion may be, wherever Arjun the mighty bowman may be there too, without doubt, are fortune, riches, victory and good conduct. This is my firm belief. (Wilkins)

Wherever there is Krishna, the Lord of Yoga, accompanied by Arjuna, wielding the bow - there reign good fortune, victory, prosperity and sound policy. Such is my conviction. (Swamy Tapasyananda)

22-Sep-2018

More by : P. Ravindran Nayar