Apr 30, 2025

Apr 30, 2025

Bulls Milk

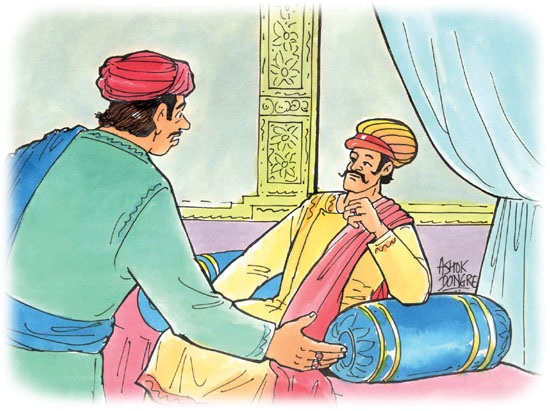

One day King Akbar became sick. He had a bad pain so he buy pain medicines. The doctor came immediately, examined the King, and then said: “I have a very good medicine here. It will quickly make you well again, but you must take it with bull’s milk.”

Then he took a small bottle from his box, and gave it to Akbar. The King was very surprised, for he had never heard of a bull that gave milk. “How is it possible?” he asked.

“Is there not some mistake?”

“No, sire. Order Birbal to get it for you. He is very clever; he can do anything.”

The doctor hated Birbal, who had put an end to some of the bad things the doctor did, and he thought this would be a way of making trouble for him.

After the doctor had gone, King Akbar sent for Birbal and told him what had happened. Birbal immediately understood that the doctor was trying to make trouble for him.

“But how can a bull give milk?” asked Birbal. Akbar became angry. “I don’t know,” he said, “but the doctor says that cow’s milk, or that of any other female animal, is of no use to me. Go and get some bull’s milk at once.”

Birbal knew that it was better not to say more. He bowed low and went away.

When he reached home, he ate his meal, and then sat thinking how to get the required bull’s milk. His daughter, seeing Birbal looking so serious , asked him what the matter was.

“Is all well at the court?” she said.

“The court is full of strange happenings,” was the short reply. “They need not concern you.”

But Birbal’s daughter knew that something was worrying her father, and at last she got the story from him. On hearing of the King’s strange request for bull’s milk she said: “Don’t worry father. I will help you.”

Next day she collected some old clothes, went to the bank of the river near the palace, and chose a spot immediately beneath the king’s bedroom window. In the middle of the night, when everyone was asleep, she started to do her washing. First she wet the clothes in the river, then beat them with a stick. With each stroke of the stick she shouted. “Thud, thud!” went the noise of the stick. “Hoish, hoish!” shouted the girl. The king was soon awake and was angry at the noise. He sent for a guard and ordered him to find out what was the matter.

The soldier came out to look for the person who had prevented the king from sleeping. He found a young girl on the bank of the river.

“What are you doing here?” he called.

“Can’t you see?” was the answer. “I am washing clothes.”

“This is not the time to wash clothes. Who are you?”

“I am a human being. If that is not enough, I am a girl.”

“Whose daughter?”

“My father’s” was the reply.

“Who is your father?”

“My mother’s husband.”

“So you are trying to be clever,” said the soldier. “Come with me to the king. We shall see what you have to say to him.”

He led her into the palace to King Akbar himself. He told the king what had happened. This made Akbar angry. Turning to the girl, he said severely, “Who are you? Why have you come to wash clothes outside my window?”

The girl pretended to be afraid. “Sire,” she said, “I had to wash clothes at night. This afternoon my father had a child – a lovely boy. I was busy all day because of that. Then I found there were no clean clothes for the baby, so I had to come and wash them at night. Excuse me, Sire.”

“What!” cried Akbar. “Are you trying to make a fool of me? Or are you mad? Whoever heard of a man having a baby?”

“Sire, up till now I have not heard of such a thing, but recently strange things are happening in this city.”

“What do you mean?” asked Akbar.

“Well, Sire, if the king himself orders someone to get bull’s milk for him, why cannot a man have a baby?”

Akbar then understood, and, smiling at the girl, he asked if she was any relation to Birbal.

“Yes, Sire, I am his daughter.”

Akbar was a just and fair-minded king. He did not become angry, but was filled with wonder at the girl’s courage and cleverness.

“You may go and tell your father,” he said, “that Akbar has received the bull’s milk. It is to be fed to the baby that Birbal has had.”

“But, Sire, how will my father believe me?”

“I will write it out for you,” said the king, and, going to his writing-desk, he took a piece of clean paper and wrote: “The bull’s milk sent through your daughter has been received.” He then signed it, and gave the paper to the young girl.

The doctor was very surprised when Birbal showed him the paper. He was so surprised that he felt ill enough to leave the sick people he was attending, go to his room, and drink some of his own medicine.

Gulbo The Tailor

One day Akbar and Birbal were talking after a meal. Birbal said that some workmen were so clever that no matter how closely they were watched, they were always able to steal some material from the man who employed them. Akbar did not agree, for he thought that a watchman could be set to prevent any stealing. Birbal said that tailors always took a piece of cloth, if some material was given to them to make clothes; but Akbar said that no tailor could take anything if he were given the right amount of material. Akbar decided to try for himself. He had, he said, some very special cloth. There was just enough to make a blouse for the queen It was a lovely piece of material and there was nothing else like it in the city. Birbal knew a tailor who could make the blouse. He was called Gulbo.

Next day Gulbo was sent for, and came to the palace. His wife and son lived with him nearby. Birbal arranged for the blouse to be made, and told Gulbo that he would be watched so that no material might be stolen. Gulbo saw the cloth and was given a blouse to copy; and he agreed to make a blouse for the queen. Akbar took him to a closed room in the palace, set three courtiers to watch, and waited. Even the tailor's meals were brought to him.

For four days Gulbo worked, cutting and sewing. On the fifth day Gulbo's son, Nathia, came to the window of the room where his father was working.

'You are a good father!' the boy shouted. 'For four days you haven't been home. Mother is very angry.'

'That is no reason to shout so,' answered Gulbo. 'Remember this is the king's palace, not our street at home.'

'Perhaps so,' was the shouted reply, 'but when are you coming home?'

'When the queen's blouse is finished – tonight, I expect.'

'What kind of tailor are you? A blouse is a matter of two hours or so, and you have already taken four days over it.'

'What do you know about it, you fool?' shouted Gulbo angrily. 'This is not your mother's blouse; it is for the queen.' Nathia only laughed.

'Your hands have become slow in making blouses for my mother.'

The courtiers watching Gulbo laughed. They regarded this family quarrel as good fun.

'You little fool,' shouted Gulbo, 'you son of a donkey, do you want a beating?'

'Wait till you come home,' was the answer. 'We shall see who gets a beating; you called my mother a donkey.'

'Go away!' called Gulbo. Then he took his shoe and threw it out of the window at Nathia, who only laughed. The boy took the shoe and ran off shouting, 'Now we will see who gets a beating with this shoe.'

That evening the blouse was finished, and Akbar gave it to the queen, telling her that there was no other like it in the city. Gulbo was paid and allowed to go.

A few days later the queen was out driving in the city. To her surprise she saw at a window on one of the houses a woman wearing a blouse of the same kind as hers. She was angry, as any woman would be, and immediately went back to the palace. At first she would not tell Akbar why she was angry, but at last she explained.

'You told me that no other blouse in the city was like mine,' she said. 'Now I have seen one- I expect there are plenty like this in the city.'

Akbar was surprised, for he had gone to great trouble and expense to get the material. He sent a servant to find out who had been wearing the blouse. After a short time the man returned, saying that Gulbo the tailor lived in the house, and that it was his wife who had a blouse like the queen's.

Akbar sent for Gulbo. 'I trusted you,' he said, 'with this expensive material, and you secretly stole some of it.'

'No, sire. I didn't steal any. How could I, when your courtiers were in the room to watch me?'

'How do you explain, then, that your wife is wearing a blouse of the same material as the queen's?'

Gulbo told Akbar how his son Nathia had come to the window of the palace, and of the quarrel.

'Sire,' he finished, 'it was only when I went home and saw my wife wearing the blouse of that material that I remembered that I had put into my shoe some pieces of the cloth which I had cut. Nathia took the shoe home. When I saw my wife wearing that blouse, I told her togive it up, but she refused. You, Sire, know what women are.'

Akbar sent for Gulbo's wife, and asked her if this story was true.

'Ah, Sire, my husband may be mad, but I am not. How could I give to the queen something that had been in his old shoe? How could I let her have something I had worn myself? Finding the pieces of material in his shoe, I thought they were for me, so I mad a blouse. I was trying to explain all this to my fool of a husband when your guards came for him.'

Akbar was surprised that a simple woman could make such a clever reply. Then he remembered that Birbal had come from a village many miles away.

'Where did you come from, Gulbo?'

It was the same village where Birbal had lived.

Pandit Ji

In the city of Delhi there lived a Brahmin called Karunashankar. He was rich, he owned his house, and he appeared to have all the things he could wish for; but he was not satisfied. He wanted to be known by the name Panditji, which means a clever man who has been to school, a man with a knowledge of religion and other subjects.

This man could not get what he wanted, for he had not the right kind of brain. He took lessons from clever teachers, but every night he forgot what was taught to him during the day, so that he had to start again every morning. At last both he and his teachers decided to give up their work; so Karunashankar remained plain Karunashankar.

But although he did not give up hope, Karunashankar lost his love of life. Some of his friends told him about Birbal.

“Why not go to see him?” they said. ‘He may know of other ways besides study.’

So one day Karunashankar came to Birbal, who saw him because he respected all Brahmins.

‘I want you to advise me,’ said Karunashankar.

‘I am quite willing,’ said Birbal. ‘What is the matter?’

‘Ever since I was young, I have wanted to be called Panditji.’

‘If you study –‘ began Birbal.

‘Study will not help me. I cannot remember what I am taught. My teachers and I have realized that lessons are a waste of time and money.’

‘Then how can you become Panditji?’

‘That is why I have come to you. Can you help me?’

Birbal told the man he knew of no secret way to learning without study.

‘I only want to be called Panditji,’ said the Brahmin. ‘I cannot learn or study.’

‘Is that all you want?’ asked Birbal. ‘You want people to call you Panditji whether it is true or not?’

The unhappy Karunashankar said it was so. ‘I shall remember how kind you are,’ he said, ‘all my life.’

‘If your memory is so good, then you need not have come to me for help,’ Birbal could not help saying, but he added that he would do what he could do.

When the Brahmin went out, Birbal called to some boys playing in the street.

‘You see that man? Call “Panditji” after him.’

‘Why?’

‘Call the name after him and see what happens.’

So the boys called out, ‘Ho there, Panditji!’

Karunashankar stopped, raised his stick and shouted angrily, but they called him Panditji all the more. Boys are like that. Some people passing by saw what was happening, and they joined in calling out ‘Panditji!’ Karunashankar was very angry but there was nothing he could do, especially as the whole street then began shouting ‘Panditji!’

Next day, as soon as Karunashankar was seen in the street, people called ‘Panditji!’ after him. This went on for a week, and then Karunashankar grew tired of being angry. He came to be known everywhere as Panditji.

The Ghee Merchants and the Gold Mohur

The king often asked Birbal to settle quarrels among the people. Even the judges sent Birbal difficult cases. You will see why, from this story.

One day a ghee merchant came to Birbal. ‘Your honor,’ he said, ‘some time ago I lent a thousand rupees to a friend when he was in need of money. Now he refuses to pay me the sum.’

‘Have you no receipt in writing?’ asked Birbal. ‘Or was no one present when you lent the money?’

‘No answered the man. ‘I have nothing to prove it. We merchants often help each other without a written agreement, but God knows I am telling you the truth. This time my own friend has not been true to me.’

‘Write down what you say, and sign it,’ said Birbal. ‘I shall think over the matter, and tell you later what must be done.’

After the merchant had written down and signed his statement, he went away. Birbal sent for the other merchant.

‘What a lucky day it is for me!’ began the merchant, but he changed his mind when Birbal showed him the statement. ‘ What a bad world this is!’ he said. ‘Even my friend does not tell the truth about me.’

‘It seems to me that it is a good world,’ said Birbal. ‘Then this man never lent you the money?’

‘No; I have helped him many times, and this is how he thanks me. It must be because my shop has succeeded and his has not.’

You say there is no truth in this statement?’

‘None at all, sir. I have not touched any of his money. If he had lent me such a large sum, he would surely have the receipt.’

‘There is no receipt and no proof,’ said Birbal quietly.

‘It is clear then, sir, that this statement is not true. It has been made only to harm me.’

‘That is what I thought,’ said Birbal. ‘But as the statement was made, I had to make sure. I am sorry you have been troubled.’

The second merchant then left.

The next day Birbal bought two large tins of ghee. He then sent one to the first merchant and asked him to sell it for him as it was not quite pure. ‘Bring me the money later,’ he said. Birbal sent the other tin to the second merchant with the same request.

As soon as the two merchants reached their shops, they poured the ghee into a pot to heat it. In doing so they discovered a gold mohur at the bottom of the tin. The first merchant took the piece of money immediately to Birbal.

‘This gold mohur,’ he said, ‘was left in the tin by mistake.’

Birbal thanked him. He was now sure that this man was honest.

The second merchant picked up the gold mohur, and decided to keep it. He called his son and said: ‘I have found a gold mohur in this tin. Keep it carefully. When I want it I shall ask you for it.’

Having sold the ghee, both merchants came to Birbal to give him the money from the sale.

Birbal thanked the first and let him go, but he said to the second:

‘The tin contained one and a half maunds* of ghee. You have given me the money for only one maund.’

‘No, your Honour,’ replied the man, ‘the tin had only one maund. I weighed it before pouring it out to heat it. My son was there at the time.’

‘Perhaps I was mistaken,’ said Birbal. ‘Please wait while I make sure.’

Birbal went into another room, called his servant and gave him the second merchant’s address. ‘Call the man’s son,’ he said. ‘Tell him to come here. His father wants him to bring the gold mohur which he found in the tin.’

After a short time the servant returned with the boy. The merchant was naturally surprised to see his son.

‘Have you the gold mohur?’ asked Birbal. ‘Yes, your Honor, here it is.’ The boy brought it out of his pocket.

‘Only one? said Birbal. ‘Did not your father say there were two in the tin?’

‘Why did you say that, Father?’ asked the boy. ‘When did you find two? You gave me only one to keep for you.’

The merchant moved from one foot to another. He understood that he had been caught, but he still tried to save himself.

‘You are a fool,’ he said angrily. ‘Who in the world would put a gold mohur in a tin of ghee?’

The son was even more surprised, but he said patiently:

‘How can you say such a thing, Father? That day when you were going to heat the ghee you picked a gold mohur from the tine. Don’t you remember that you asked me to keep it for you?’

‘You must have dreamt it,’ said the merchant. ‘I remember now that I did give you a gold mohur to keep, but I got it from a man who came into the shop.’

‘It was no dream,’ said Birbal, who was listening. Then, turning to the merchant, he added: ‘ I put the mohur in the tin myself to test you, to see if you are honest.’

‘Perhaps I forgot what actually happened,’ said the merchant. Why should I keep someone’s money? Boy give Lord Birbal the gold mohur.’

Birbal took the piece of money from the boy, then said quietly, ‘You have returned my mohur. What of the thousand rupees you borrowed from your friend?’

Hearing the first merchant’s name, the boy broke in:

‘Haven’t you returned the money yet, Father?’

“You keep quiet,’ shouted the merchant angrily, but Birbal told the boy to tell all he knew. The boy then described how his father had borrowed a thousand rupees from the first merchant, and had said that he would soon pay the money back.

‘It seems,’ said Birbal, ‘that your son is more honest than you. Take a lesson from him. If you were ready to steal one gold mohur, you would be more ready to steal a much larger sum. Come, tell the truth.’

Seeing that he was caught at last, the merchant agreed that he owed a thousand rupees to his friend. He had to pay. It was in this way that Birbal became famous for discovering who was honest and who was not.

The Old Woman's Money-Bag

There lived in the city an old woman whose husband had died, and she had no one to care for her. One day she decided to go on a pilgrimage to Kashi. She took out her money-bag, which was full, for she had saved money all her life. Part of the money she kept for her expenses on the way, the rest she exchanged in the market for gold-mohurs. She marked these in a certain way, then put them into her money-bag, which was made of cloth. She went to an important citizen, a man who attended to matters of religion.

She said to him, ‘Sir, I am going to Kashi on a pilgrimage, and I am afraid I may be robbed on the way. May I leave my bag of money in your safekeeping?’

‘My good woman, why do you bring the money to me? I have enough troubles.’

‘It will not be any trouble. If I return in three years or before, I shall take the bag again. If I do not return in that time, take the money and give it to the poor.’

This man was much respected and considered to be a good man. He agreed at last to look after the bag.

‘I never touch money myself,’ he said. ‘Take the bag and bury it yourself in that corner of the room. When you return, you can dig it out yourself from where you have buried it.’

The old woman went to the corner and buried the money-bag. She was careful to mark the place.

‘Go now,’ said the man. ‘May God bless you! When you return, don’t forget to get me something from the temple.’

A year and a half went by. The man began to think the old woman would never return, so he took out the bag, emptied it of the gold mohurs and put copper pieces in their place. He had the bag sewn up exactly it was before. Then he buried it again in the corner of the room.

After about two and a half years, the old woman returned to the city. Next day, she took what she had brought from the temple and came to the citizen’s house.

‘You see, sir, I have not forgotten,’ she said, as she gave him what she had brought.

‘How are you, my good woman? I see you have returned safely after all. Thank you for bringing this from the temple at Kashi.’

‘Thanks to your wishes and blessings I am safe,’ she continued. ‘Now may I please have my money-bag?’

‘You know I never touch money,’ he replied. ‘You buried the bag yourself; you had better get it out from where you put it.’

She went to the corner, found her mark, and dug up the bag.

She was pleased to see it sewn up as she had left it. But when she got home, she was frightened to find that the bag contained copper pieces instead of gold. She went back to the man’s house.

‘Sir, what is this?’ she asked. ‘The bag now contains only copper. I had put gold mohurs into it.’

‘Look, my good woman, I have not touched your bag. I do not know what it contained. It was exactly the same as when you went away.’

‘But, sir, the gold mohurs were my life’s savings. Perhaps some servant did this.’

‘No servant knew anything about the bag or even where it was buried.’

‘Sir, I beg you. If you like take half the gold mohurs for keeping the bag for me, but give me the other half.’

‘I am a man of religion. I have no money; I certainly haven’t got yours. I think you had better go.’

She began to cry, and through her tears told him that God would punish anyone who treated an old woman so, but it had no effect. The man called a servant to throw her out.

At her home, her friends advised her to see Birbal, so, a few days later, she went to see him. She told him the story, and Birbal sent for the citizen.

The man sat with folded hands. ‘Sir,’ he told Birbal, ‘about three years ago or less, this woman came to me with her bag of money. She wanted to leave it with me while she was away on a pilgrimage to the temple at Kashi. It is, as you know, against our religion to touch money, so I did not want to keep the bag, but she begged me so hard that I let her bury it herself in my house. You may ask her if this is true.’

‘It is true, said the woman, ‘but when I buried the bag, it contained gold mohurs. When I dug it up it was full of copper pieces.’

‘How did the gold turn to copper?’ asked Birbal.

‘Sir,’ answered the man, ‘the bag was of cloth, sewn up, and could not have been opened. The woman must be mistaken. The memory of old people is not always good.’

The way the man described the bag made Birbal feel doubtful. He told the woman not to worry and let the man go.

That night Birbal made a small cut with his scissors in the sheet on his bed. In the morning, the servant who was making the bed saw the cut. It was a new sheet and the servant was afraid that his master would be angry. He found from an older servant that a tailor called Rafiq could mend it well; he was very good at mending old clothes. The servant took the sheet to Rafiq and got it mended. At night Birbal examined the sheet but could not see where he had cut it. He called the servant, who was at first frightened on being questioned about the sheet and the cut.

‘Don’t be afraid,’ said Birbal. ‘I did it myself. But I should like to know who mended it so well. I cannot see where the cut was.’

‘His name is Rafiq,’ said the servant.

‘Send him to me. I want to thank him,’ said Birbal.

Next day Birbal saw Rafiq, and after saying how well he had mended the sheet, he gave the old woman’s bag to the tailor.

‘Do you remember this bag?’

‘Yes,’ replied the tailor after examining it. ‘Some time ago, two years or more, the servant of a man’ (and he named the citizen), ‘came to me with this bag to mend a hole in it. This is the place. I mended it cleverly and gave it back.’

‘What was in the bag?’ asked Birbal.

‘Only some copper money.’

‘No gold mohurs?’

‘No, sir, only copper.’

Birbal immediately sent for the citizen, and told him what had been said. ‘Now what have you to say?’ he demanded.

The citizen could not say anything. He knew he was caught.

‘I know you do not touch ordinary money,’ said Birbal, ‘but perhaps gold is different. Gold is pure and clean, isn’t it? A pure, clean man like you should not be with people who are not the same. Perhaps they are not honest.’

He called a guard to take the man away. The citizen then became frightened. He realized that he might be sent to prison and so told the truth.

‘Yes, I took the gold mohurs. Here they are.’ He gave the money to Birbal, who sent for the old woman and gave her money back to her. Although he did not go to prison, the citizen lost the respect of other people. He became ‘that old man’.

The Three Cases

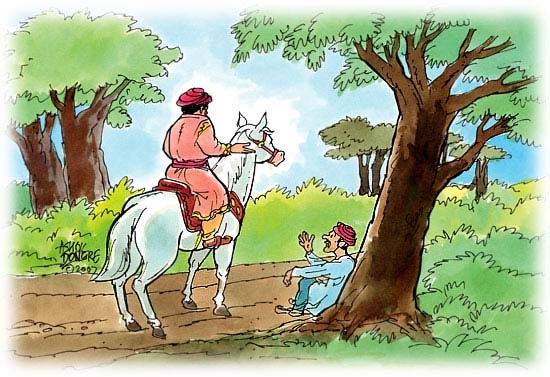

Suryasingh, the prince of Manipur, once came to the city of Delhi on business; but, as it was secret, he did not inform anyone before he left home, nor did be bring a single servant with him. This explains why an important man like the prince was traveling alone. On the way he saw a weak and tired-looking man sitting beside the road. He felt sorry, and said to the man: ‘Which way are you going?’

‘Good Sir’, was the reply, ‘I have to go to Delhi, and must be there before night, but I shall never reach the city, for I am tired.’

Suryasingh got off his horse, and told the man to get on it instead of him.

‘If you go slowly,’ he said, I shall be able to keep up with you. I like walking. I also am going to Delhi, but I do not know the road very well. You can show me.’

The man seemed to be waiting for this offer and he gladly got on the prince’s horse.

Suryasingh walked beside him. At the city gates, Suryasingh asked the man to get down.

The man looked surprised. ‘Why should I get off the horse?’ he said.

The prince explained politely, ‘Now that we have reached the city,’ he said, ‘we shall have to separate. I am staying here and do not want to be late.’

‘You may go where you like,’ was the reply. ‘I am not stopping you.’

‘But give me my horse first,’ said Suryasingh.

‘Your horse? Do you say it is yours?’

‘Of course, do you doubt it?’

‘You are taking advantage of a kind man,’ was the answer. ‘I showed you the way to the city. Now you say my horse is yours.’

‘Your horse?’

‘Yes, mine,’ said the man.

Before he could ride away, Suryasingh took the rein. ‘Let us go to the judge,’ he said.

The two came to Birbal, who was judging cases. They had to wait while these were finished. The first was a quarrel between a butcher and an oil-merchant.

Birbal asked the oil-merchant to give his story first.

‘Sir,’ he said, ‘ I was sitting in my little shop, counting money and writing the amounts in my book. This butcher came for some oil. I gave him what he asked for, took the money and started on my books again. Meanwhile this man took the bag of money beside me, and walked off with it. When I saw this, I stopped him and took back the bag. He wanted to fight, and said the bag was his.’

Birbal turned to the butcher. ‘What have you to say?’

‘Sir,’ answered the butcher, ‘This man is not telling the truth. I bought some oil from him, and paid him from this bag. Then he ran after me, saying the bag of money was his, and that I had stolen it. There were no people in the shop, or I could prove it.’

‘Leave the bag with me,’ said Birbal. ‘I shall give the answer tomorrow at this time.’

Birbal then called an old woman, who told him that she had left her box of precious stones with the judge in her village, while she was away a short time.

‘I trusted him,’ she said., ‘but when I came back, he said that he had never seen the box or the stones.’

Birbal thought for a moment or two. Then he said to the woman: ‘Go back to the judge, and ask him again for the box.’

lsquo;He will use the same harsh words as he used before,’ she said, not wishing to try again.

‘There is no harm in trying,’ said Birbal. ‘Come back at this time tomorrow, and tell me what has happened.’

When she had gone, Birbal asked Suryasingh politely what he could do for him. He heard the story of the horse from the prince and the traveler.

‘Leave the horse with me,’ he said. Tomorrow I will give it to its owner’.

After both men had left, Birbal told his servant to take the horse and to follow the two men at a distance, then to free the animal and see which one of the two it followed. Afterwards he was to bring it back and put it in the stable with others of the same color and size.

The next day, many people were present to hear Birbal, for they wanted to know what he would say in these cases.

Birbal gave holy books to the oil-merchant and the butcher; each said, holding the holy book, that he owned the money-bag. Birbal gave the bag to the butcher. ‘You spoke the truth,’ he said, and called guards to take away the oil-merchant. The latter fell on his knees and begged for mercy.

‘How can I show mercy to one who says what is not true, and says it by the holy book?’

After that, Birbal called the old woman. She said happily that the judge had given back her box of precious stones. Birbal was very angry with the judge.

‘You are there to give justice,’ he said, ‘not to rob poor people. You will lose your position.’

Then Suryasingh and the traveler were called, and taken to the stable. There were about a dozen horses there, mostly of the same color.

‘Your horse is here,’ said Birbal. ‘Take him.’

The traveler tried, but could not see which was the horse, but Suryasingh found him at once. The horse knew its master also.

‘This kind man,’ said Birbal to the traveler, ‘offered you a ride on his horse, and you tried to rob him. You shall have fifty strokes of the whip.’

Suryasingh took the horse and returned to the court. When everyone had gone, he said to Birbal: ‘Sir, I have to inform you who I am and where I come from.’

‘There is no need, Suryasingh,’ was the reply. ‘I did not ask for your name and address.’

‘You know me, then? I thought it was secret. I heard you were famous for judging, and I wanted to see you.’

‘I know you to be the prince of Manipur,’ said Birbal quietly. ‘We have a large country to rule and it is our business to know who is coming. The government have arranged for your stay here.’

Suryasingh thanked him. ‘There is one more thing,’ he said. ‘I heard your judgments, but I should like to know how you decided in these three cases’.

‘Willingly,’ replied Birbal. ‘In the first case, that of the butcher and the oil-merchant, you may remember that I took the money-bag. I did not leave it here but took it home. When I had emptied it, I washed it. When it was dry, I put the money back inside. But I examined the water carefully, and found it was slightly red; it smelled of blood also. I knew then that it belonged to the butcher.

‘In the case of the old woman and the judge, I felt from her words and the way she behaved that she was telling the truth. To make sure, I had a message sent to the judge that he was to take the place of the chief judge here while he was on a holiday. The message came to him before the old woman did. The judge was afraid that he might lose the position if she made trouble for him just then, so he gave her the box back.

‘As for your case, I knew who you were, and could not think that a man in your position would say what was not true for the sake of a horse. But my feeling was not enough; justice must be clear to all. My servant followed you both with the horse, and set it free; it went after you not the traveler. He could not find it in the stable, but you had no difficulty.’

The prince went away surprised by Birbal’s wisdom.

26-Oct-2019

More by : Shernaz Wadia