Jan 01, 2026

Jan 01, 2026

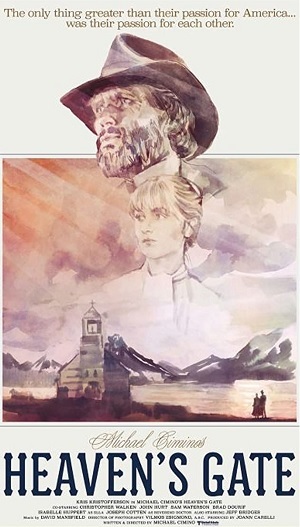

Heaven’s Gate at 40 – Michael Cimino’s elegy to the lost idealism of youth amidst the rarefied air of Montana’s Glacier National Park

“I give you the end of a golden string

Only wind it into a ball

It will lead you into heaven’s gate

Built in Jerusalem’s wall”. — William Blake (1815)

In the history of Hollywood, few films have been lambasted or ridiculed with such unremitting fury as Heaven’s Gate. In his search for perfection and lasting art, Michael Cimino became so self-absorbed and obsessive in his vision and grandeur, that the film was doomed by the time it was screened in 1980. Given total carte blanche in only his third film, even the cache and prestige accorded to him by his previous feature, the Oscar-laden the Deer Hunter, was not enough to save it as reports filtered through of extravagance, excessive attention to detail, spiralling costs, production delays, endless takes, procrastinations and interminable wait for the right moment for the clouds, ground and the mountain to be in total harmony with each other. Known as the Ayatollah on the set, he didn’t help himself by being unresponsive and uncommunicative with regard to updates and briefings. Such bloated egoism and hubris won him very few friends within the industry and as news spread of his autocratic behaviour amidst soaring budget, influential sources were salivating at the prospect of his impending comeuppance. Cimino’s retort, in his defence, of “look what’s on the screen” would not be enough.

In the history of Hollywood, few films have been lambasted or ridiculed with such unremitting fury as Heaven’s Gate. In his search for perfection and lasting art, Michael Cimino became so self-absorbed and obsessive in his vision and grandeur, that the film was doomed by the time it was screened in 1980. Given total carte blanche in only his third film, even the cache and prestige accorded to him by his previous feature, the Oscar-laden the Deer Hunter, was not enough to save it as reports filtered through of extravagance, excessive attention to detail, spiralling costs, production delays, endless takes, procrastinations and interminable wait for the right moment for the clouds, ground and the mountain to be in total harmony with each other. Known as the Ayatollah on the set, he didn’t help himself by being unresponsive and uncommunicative with regard to updates and briefings. Such bloated egoism and hubris won him very few friends within the industry and as news spread of his autocratic behaviour amidst soaring budget, influential sources were salivating at the prospect of his impending comeuppance. Cimino’s retort, in his defence, of “look what’s on the screen” would not be enough.

Yet the years have been kind to the film. Viewed through the prism of hindsight, separated from the detritus of unpleasant criticism and an avalanche of cynicism, sarcasm, lack of empathy and understanding; extrapolated from the mythology of its production to be seen as a film, rather than the ambitious and visionary epic with a grand statement, it holds up as a majestic, revisionist tale set in turbulent times which asks probing, searching and uncomfortable questions about a country and its people; perhaps, audiences found it uneasy and disturbing in the way a nation dealt with immigrants on the picturesque but rugged plains of Wyoming. Cimino doesn’t bathe the story in syrupy and saccharine tones; instead it is presented in unadulterated, violent strokes to show the attitude of the power-brokers towards the European settlers in a hostile territory. For all its scenic grandeur, the dirt and the dust, the bloodshed and the ruthlessness, the mud, the arctic cold, the living quarters on the vast plains, are all too real. Though a work of fiction based a historical incident, it doesn’t show the host country in a favourable light.

Divided into three parts, separated but linked by 33 years, from 1870 to 1903,

Heaven’s Gate is not so much a Western much misunderstood, but a historical period drama, based on the Johnson County War covering the years 1887 to 1893. The prologue covers the Harvard graduation in 1870, shot in Oxford, showing the close friendship between the privileged and wealthy Easterner Jim Averill and the cerebral orator William Irvine. The Reverend Dean urges the new alumni to “teach culture to the uncultured, educate the uneducated” before the ceremony closes with a waltz on the sacred lawns to the sound of Johann Strauss’s the Blue Danube. A rapid cut brings the scene to a close; twenty years later we are in the bustling city of Casper, Wyoming, where Jim arrives by train, observing the compartments and the main streets, crowded with immigrants confronting hostility and violence. In the Wyoming Stock Growers Association building he is reunited with ‘Billy’ Irvine; the latter asks Jim if he remembers the bygone times. “Better and clearer, every day I get older”, comes the reply. The mood in the county has clearly changed; from teaching culture, learning and education to others, the two friends are facing the reality of seeing their ideals crushed; the businessmen and power-brokers, with the tacit approval of those in high authority, have openly waged a war on the immigrants, offering rich rewards to vigilante gunmen to kill the foreigners who are perceived as thieves and anarchists. They are in the crossfire of a brutal war. Billy takes refuge in drink, muttering monologues to himself; Jim is the Marshall and must side with the downtrodden victims. Nate Champion is the leading gunman, tasked with the killings; he is also involved in a love triangle with Jim and a local madam, Ella Watson.

Initially reluctant, Jim watches from the side-lines, joining the persecuted foreigners for a song, waltz and some sanctuary in the titular Heaven’s Gate where, on an ice rink, inhibitions and fears are cast aside for brief moments of joyous exuberance; ironically, a few reels later, he is forced to read out the names of 125 immigrants on the death list compiled by the Stock Growers’ Association. War inevitably ensues, Jim enters the fray, even helping to form a Trojan horse, in a nod to the Siege of Troy. The US army arrives and arrests the leader of the Association; Nate, Ella and Billy are killed; heart-broken and emotionally scarred, Jim moves out of the territory back to East coast.

In the 1903 epilogue, Jim is on a yacht in Newport, Rhode Island, older, sadder and wiser, with a woman, perhaps his wife or former girlfriend below deck; he lights her cigarette, returns upstairs and, one assumes, remembers Ella before the credits start to roll. The emptiness of his life is emphasised in a dream-like sequence which is almost wordless. This coda is a homage to the finale in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 when man is reborn in a chamber on Jupiter as the cycle of life continues even in space. The advertising slogan for the film was “what one loves in life are the things that fade”, a sort of yearning for lost youth and its ideals; this offers a neat juxtaposition to what Michael Cimino is implying in his perceived vision: what one loves about life are that people come and go, time-lines run their course, but monuments and art survive for perpetuity.

Jim, Ella, Nate and Billy were essentially minor characters who lived through the Johnson County War as did Frank Canton, the leader of the Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association. In their fictionalised personas, they are brought to life as real people caught up in a turbulent war outside their control; their aspirations, ideals, social status and personalities, form a human element and fulcrum to give the narrative the character and context to drive the story forward. Their shortcomings and weaknesses are laid bare even as the threat of vigilante action escalates; they exist outside of the war and as central figures within the turmoil of it. The film is as much about their fate as it is about the war, even if some aspects of their background, including the romantic triangle story, are not fully developed. In the final analysis, they are cursed and doomed. Jim and Ella were hung from a tree in the summer of 1889, the latter for accepting stolen cattle as payment for her services. The fates of these protagonists hang like a black cloud over the grandeur of the landscape.

By January 1892, America had softened its stance towards the immigrants even as the Johnson County War, referenced in the films Shane and the Virginian, was drawing to a close. The building of Ellis Island outside New York was seemingly an act of redemption as the country opened its doors to a new wave of European immigrants; in subsequent decades it became the great polyglot melting-pot it is today, rewarding thrift, hard work and allegiance to the new mother nation. The sonnet, the New Colossus by Emma Lazarus, was mounted inside a pedestal’s lower level on the iconic Statue of Liberty, reverberating with a fervour and depth of feeling that is deeply touching:

“Give me your tired, your poor

Your huddled masses

Yearning to breathe free

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless,

Tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the

golden door!”

If the opening Harvard sequence, with its revolving, dizzying camera, its theatrical, regal movements of the dancing graduates to the tune of the Blue Danube, is extraordinary, equally remarkable is the ice-skating sequence in the eponymous Heaven’s Gate in the town of Sweetwater. It is here the persecuted and despised immigrants arrive on a Sunday morning, a sanctuary of a ‘home’ far from home, to congregate, talk, laugh, play music and dance; the scene, in a more prosaic surrounding than the Harvard lawn, is quite beautiful, a rare fleeting episode, frozen in time, of transitory happiness, in contrast to the nihilistic violence they confront outside the building and the expansive plains. The climactic battle scene is another tour-de-force of artillery and explosions, dirt and white dust, blood, whirring, furious movements of galloping horses at breakneck speed as if in a race and riders observed from multiple angles through a cloud of smoke; the colours are muted and solemn, brown being the dominant in this surreal theatre of war; the noise, chaos and confusion all captured in the sheer, physical force of the blur of violence as if war was aesthetic art, with the camera pulling back frequently to show, in deep focus, moments of repose before hostilities recommence.

The length of the film, all 229 minutes of it, is prohibitive and clearly an anachronism in the modern era of instant gratification. But it is worth asking whether true art, as conceived by its author and creator, should be seen and watched only in a truncated, condensed and compressed form, rather than in its full aesthetic glory, especially when he has created a rich, variegated mosaic that questions, challenges and probes the way we look at something that is different in scope and vision, that has been painstakingly created and realised with authenticity and accuracy. The title Heaven’s Gate itself suggests something preternatural, something grand, resonant, paradisal and to be revered. Perhaps there are not enough connoisseurs left in the world anymore. Johnny cash captures something of the mythical element in hIs cover of Sheryl Crow’s Redemption Day:/p>

“I have wept for those who suffer long

But how I weep for those who are gone……..

There is a train heading straight

To heaven’s gate, heaven’s gate

And on the way, child and man

And woman wait, watch and wait

For redemption day.”

27-Sep-2020

More by : Kewal Paigankar