Jan 23, 2026

Jan 23, 2026

It was a warm and humid summer evening back in 2017 in El Dorado, in North Eastern Trinidad. I was sipping the local rum with Lal at his house. Lal is an 80-something Caribbean man. His son Barry is my neighbor in London, and we were visiting the island together with our families. Lal had cooked delicious jeera pork and rice for us earlier that evening.

We’d both had a few and were both quite drunk. Suddenly, Lal leans over, taps me on the shoulders and asks, “Are you from India?” Obviously, I say yes. “So was my great-great grandfather, I heard tales from my grandfather of the ships arriving in the Caribbean from India.” He pauses, and then contemplates, “As I get older, it feels like I’m from India too, even though I’ve never been there. Ha ha. How odd.”

I stayed silent, knowing he was in the middle of his contemplation. “I don’t know what the surname ‘Radoo’ originally was, but my name is Chunilal and I am from Uttar Pradesh. Have you heard of Uttar Pradesh?” Shortly thereafter, he passed out drunk and the next morning he was ‘Lal’ from El Dorado again.

I felt the connection everywhere on the island. From driving past supermarkets owned by Bhagwan Singh, to observing Barry’s mother-in-law watching Hindi TV serials with English subtitles, to eating ‘doubles’ (essentially two pooris) and chana by the roadside, to the Hindu and Muslim festivals they celebrate, it felt like a home away from home.

Whilst being driven around the island, I noticed a massive pink humanoid statute in the distance. When I asked Barry about it, he said nothing but smiled. We continued driving, and soon noticed signs pointing to Carapachaima. A bit further along I noticed signs to the Dattatreya Temple. As we got closer, I saw that the statue was around 80 feet (85, in fact) tall and was that of pavan putra Hanuman.

I’ve been to hundreds of temples in my lifetime, but this felt special, almost 9,000 miles away from India, here was a symbol of our culture that our brethren had preserved so pristinely. Sure, there are beautiful Hindu temples elsewhere in the world, such as the Swaminarayan Temple in London, but this felt different, it was literally on a rock in the Atlantic Ocean on the edge of Latin America.

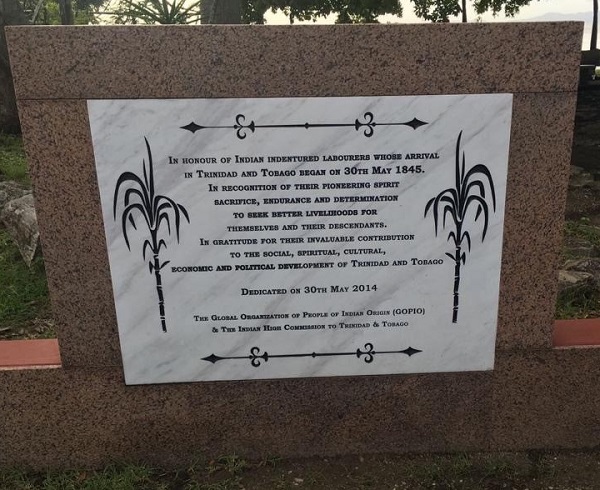

Often when we read or hear about colonial era migration, it is described in terms of indentured labourers being oppressively transported from India to Africa to build railways or to the Caribbean to work in the plantations after slavery was abolished. There is a big map in London’s Museum of the Docklands that charts the global migration pathways of Indians during the Raj. I learnt an alternative view (espoused by some of those Indians themselves) on a marble plaque outside A Temple in the Sea in Waterloo, Trinidad:

“In honour of Indian indentured labourers whose arrival in Trinidad and Tobago began on 30th May 1845. In recognition of their pioneering spirit, sacrifice, endurance and determination to seek better livelihoods for themselves and their descendants.”

It’s the last bit that gets me – “to seek better livelihoods for themselves and their descendants.” Some of those arriving in the Caribbean genuinely felt this was the right answer for their families’ future. No doubt the same was felt by Indians who travelled to Kenya, Uganda, Guyana, Fiji, Mauritius, Maldives and to this day this sentiment is present amongst Indians moving to the US, the UK, Australia, New Zealand or Canada in search for a better life.

One of Barry’s friends is a senior finance executive working in Trinidad. He visited India some time back and recalled the experience – “I touched down from the plane, looked all around, and something stirred in me. This was the country of my ancestors. I went to Varanasi, went to Haridwar, did all the poojas, paid all my respects and really felt it was an extension of my identity. But I also looked around and saw the (literally) billions of people amongst whom my forefathers must have realized that the chances of ‘making it’ were infinitely smaller than tackling the fear of the unknown and taking a leap of faith by boarding that ship to the Caribbean in search for a different, and hopefully better life.”

Indians (or people of Indian origin) send over $80 billion back home every year. I too am a rounding error within that number somewhere. I know that the Indian government either runs, sponsors or supports various NRI or PIO events which foster closer relationship between India and various overseas Indian communities. However, I can’t help but feel that there is more that can be done. There is a deep cultural connection between India and her people, whether or not they live in India.

The plaque showing Bheeshma on his bed of arrows in the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia is living testament to India’s cultural influences beyond its borders. It is time to contemplate a more ambitious relationship between India and her overseas children, be it visa-free travel, investment incentives or even free trade deals with all countries with significant numbers of people of Indian origin. For centuries, the idea of ‘greater’ India was not novel, it was the norm. If we truly believe in vasudhaiva kutumbakam, the first family we need to knit tighter is the global family of Indians.

Images by the author

02-Jan-2021

More by : Aruni Mukherjee