Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

Rajender Krishan (b. 1951, aka Raj Chowdhry), a renowned Indian diaspora poet living in New York (USA) since 1989 and Founder Editor of the world-famous website Boloji.com, started in 1999, an open platform, is showcasing the work of amateur and professional writers from all over the world. He matriculated from Punjab University and graduated from Delhi University. He believes in the freedom of expression and is an ardent admirer of Kabir, the secular saint poet. He owes his wonderful life to his grandmother and parents whose blessings have gifted him with a penchant for poetry, photography and the fine arts.

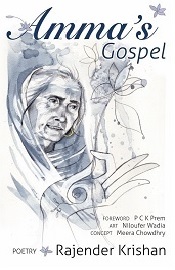

Rajender has published Solitude and Other Poems (2013), Amma’s Gospel (2020) and Wanderer (2020) Out of these I have selected one (title) poem from each of these collections for my present study. The text of the poems, given separately in the beginning of the study or the explication, would have made it unexceptionally long and unwanted. So, I have embedded the poems in the text of the study clearly stating how many lines a particular poem has.

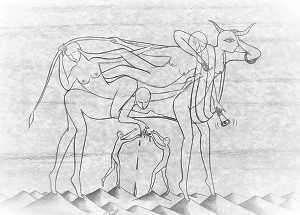

This poem, ‘Solitude’ (pp. 3-4), is from the first collection, Solitude and other poems.

This poem, ‘Solitude’ (pp. 3-4), is from the first collection, Solitude and other poems.

The poems of this book celebrate the poet’s “instinctive love” amalgamating his worldly-wise and sophisticated experiences and acuities stimulated by “the ancient wisdom of Hindu Philosophy”. In this light, let’s explore this poem that becomes the title poem.

The poem under study has five stanzas. These stanzas are irregular in their size: first has three lines; second, four lines; third consists of twelve lines; fourth of four lines, and fifth comprise six lines. In the first stanza the protagonist informs the reader that he has been working hard to find solitude but so for it has eluded him and has remained vague. The protagonist puts this idea simply in the following three lines:

I have tried hard

to discover solitude

but it remains elusive (ll. 1-3)

The poetic consciousness moves further from personal attempts to locate solitude to intelligence, which, according to the protagonist, is imperfect, yet ceaselessly drives his predetermined mind to spatial infinitude. He is not content with the finitude of his astuteness, which is ever busy in boosting his “finite mind” to widen its domain in space. This idea is plainly put in the following four lines:

My intelligence

however limited

constantly propels my finite mind

towards the infinity of space (ll. 4-7)

Now, there is the third stanza: largest in size having twelve lines. It informs the reader that his “finite mind” jumps from one thought to the other. These thoughts appear in pairs of powerful and sad, wavering and firm, contemplating and baffled, unruffled and twitchy, pleasant and unpleasant, and zealous and angry within the known and unknown precincts of thoughts surging in the persona’s mind. These do not remain discrete but blend together like a chemical compound evolving into a new thought. The poet has put this idea of different ideas appearing in mind as if boiling in a vessel/receptacle (T. S Eliot has described ideas mixing in a receptacle in his essay, ‘Tradition and Individual Talent’) in the “eternal circle” – a process that is incessant. The stanza is given below:

Hopping

from one thought to another

potent, pathetic

oscillating, resolute

pondering, perplexed

serene agitated

sweet sour

Passionate, enraged

within the known and the unknown

realms of ideas

that constantly mingle

in the eternal circle (ll. 12-19)

The poet calls this experience that goes on within the psyche or mind of the creative artist/poet as ever fresh but flustered or agitated. One, who experiences it, becomes the observer to this imaginative act within the mind. This act is indeed wonderful and mindboggling. Nonetheless, it provides unparallel delight to the subject experiencing it. See, how the poet aptly puts it in the fourth stanza:

Untiring is the phenomenon

yet unruffled remains the witness

to this incredible marvel

of pristine amusement (ll. 20-23)

While going through the poem, the reader, if s/he is able to rise and capture the poet’s imaginative height in its white heat of imagination, also experiences the same joy.

The last stanza is the crux of the situation: the poet/protagonist avers that it has been a wonderful revelation or experience for him. Throughout, He has experienced not only freedom but “the essence of freedom”.

I cannot let go

this singularity of life

where I experience

the essence of freedom

in the association

of your perpetual presence. (ll. 24-29)

The spirit of freedom, he has experienced in the sweet company of “your perpetual presence”, cannot be allowed to be ended as such. The second person possessive pronoun, “your”, that behaves, here, as an adjective modifying the noun “presence”, seems a bit ambiguous exerting pressure on the reader. The word, “your”, signifies two things and, here, too, it remains ambiguous: one, with small “y”, suggests ephemeral love; two, when the reader takes cognizance of the fact that these are “inspired by the ancient wisdom of Hindu Philosophy”, then, mysticism seems to be the core idea behind this word suggesting Almighty God – the one behind all creations, abstract and concrete.

The poet has, in this poem, put the marvellous idea giving a poetic experience magically delightful in simple words.

~*~

Amma’s Gospel (45-47) is 50 lines long and has been divided into three Sections by the poet: 1. Amma’s gospel was simple, 2. Amma would elaborate, and 3. Amma would respond. The first and third sections have 10 lines each while the middle, second section, has 30 lines. The first Section reads:

Amma’s Gospel (45-47) is 50 lines long and has been divided into three Sections by the poet: 1. Amma’s gospel was simple, 2. Amma would elaborate, and 3. Amma would respond. The first and third sections have 10 lines each while the middle, second section, has 30 lines. The first Section reads:

Love yourself

by being true to yourself

Be not in haste to react

First anticipate then contemplate

and

then respond

Follow the right path

Be happy

Be successful.

I would express my curiosity (ll. 1-10)

As its subtitle says, it is very simple. However, for our study we can further sub-divide it into four parts: in the first part (ll. 1-2), Amma would tell the protagonist to love himself and in doing so he must be true to himself. In the second (ll. 3-6), she would tell him not to respond immediately to any situation/query/suggestion. Instead, he should wait for some time expecting any other development in this period. If there is no further change or development, then he should think over it with cool mind. He should respond only after having examined the pros and cons of the situation. In the third part (l. 7), the suggestion is to follow “the right path”. And when the protagonist has followed and acted according to the first three gospels, the result would be to his satisfaction, as is clear in the fourth part (ll. 8-10), and that would lead to his happiness and success. In other words it can be said to be the enunciation of Amma’s gospel. The main points of the gospel can also be shortlisted as

On hearing these points of the gospel from Amma, the protagonist would show his interest and inquisitiveness by way of his gestures or words to know something more in simpler way.

In the second section, to satisfy the protagonist’s curiosity, Amma would elaborate the gospel in simple words. Again for our convenience, we have to divide it into four parts as shown by the poet in different stanzas. In the first part

Stop electing

the path of deceit

in the journey of life

The path of deceitfulness

makes you the key contestant

against your own very self

while cruising through

the vagaries and variables

in the play of life (ll. 11-19)

of this Section, Amma warns him of treachery. It is always damaging to one’s life. Deceit divides one’s self into two; one contests against the other in the game of life while facing the vicissitudes of life as shown here as “vagaries and variables”. Therefore, deceit should be avoided in life. It implies that one must be true to oneself.

In the next part of this Section, she tells him that this “deception” makes one “prisoner of past”: one, instead of facing the present, continues to live in the past and spoils one’s present and loses chances of success and thereby happiness. Past is “dead” and what is dead is ineffectual and worthless. One cannot live on what is dead, useless and obsolete. Yet, it keeps one haunting: one longs to emancipate oneself from the fetters of desires. The poet has put it beautifully thus:

This play of deception

sets up boundaries

to make you

a prisoner of the past

that has long been dead

yet keeps haunting

Send you simply keep longing

to be free from the bondages (ll. 20 – 27)

In the fourth part, she illuminates him that deceitfulness in the following lines:

Treacherous is this play

that hoodwinks you to become

a puppet of emotions

a victim of desires

and not the master of your mind (ll. 28-32)

When one’s emotions overpower, one becomes slave to them: therefore, one should not fall prey to one’s desires. This act that makes one slave to emotions and victim of desires deceives one in one’s life. One, instead of becoming “a victim of desires” should try to be master of oneself – one’s reasoning mind.

In the next part, she continues her elucidation of her idea that, in life, if one pretends, or deceives, or commits a fraud and untrustworthiness in “blame games’ in the play of life; it makes one an instrument of ego. As one falls prey to one’s ego - one’s “fraudulent integrity” – fake uprightness. One loses one’s self respect and isn’t able to face oneself. It is stated in the following lines:

The sham and deviousness

of playing blame games

makes you a gadget of ego

that traps and ensnares

leading to a fraudulent integrity

of tumbling self-esteem

unable to see its very own reflection (ll. 33-39)

In the last line of this stanza, “What is the way then? I would ask” (l. 40), the protagonist asks Amma ji to know the way to avoid “sham and deviousness”; so that he does not become “gadget of ego”.

In response to his query, Amma would respond by repeating her gospel

Love yourself

by being true to yourself

Be not in haste to react

First anticipate then contemplate

and

then respond

Follow the right path

Be happy

Be successful. (ll. 41-49)

This repetition of the gospel emphasizes the gospel. That it is through one’s truthfulness and cool mind one can avoid falling prey to ego that demeans one even in one’s own eyes. This gospel advocates for uprightness in one’s character.

In the last line of the poem, the protagonist/poet, like an aside in a drama, asks the readers: “Have I fathomed?” – if he has followed/understood the gospel in its letter and spirit. In fact, it is not for the protagonist, but in its guise it is also directed toward the reader. It teaches readers to follow truth and discard sham in life.

This poem, indeed, portrays the roots of our culture based on the tenets of Sanatana Dharma.

~*~

Amma ji (pp. 36-7) is a wonderful poem in 24 lines divided into four stanzas having six lines each. These four stanzas throw light on her character. The first stanza tells about her birth during the pre-independent, undivided India ruled by the Britishers. The people were oppressed by the rulers. Finally, when this country achieved independence, Amma ji became a refugee; the country was divided into present India and Pakistan. She had to leave her home and hearth in the part of country, western Punjab, which became part of Pakistan. She was without home and hearth: a refugee. She migrated from western Punjab to Delhi, present India as a refugee that was her own country before partition! The refugee life was very hard. We gather this from the following lines of the first stanza:

Amma ji (pp. 36-7) is a wonderful poem in 24 lines divided into four stanzas having six lines each. These four stanzas throw light on her character. The first stanza tells about her birth during the pre-independent, undivided India ruled by the Britishers. The people were oppressed by the rulers. Finally, when this country achieved independence, Amma ji became a refugee; the country was divided into present India and Pakistan. She had to leave her home and hearth in the part of country, western Punjab, which became part of Pakistan. She was without home and hearth: a refugee. She migrated from western Punjab to Delhi, present India as a refugee that was her own country before partition! The refugee life was very hard. We gather this from the following lines of the first stanza:

Amma, had faced the colonial

subjugation and oppression;

finally gained independence

only to become a refugee,

a migrant in her own country

in the post-partitioned India (ll. 1-6)

The second stanza tells that the trying conditions of life – “harsh transitions” – that she underwent while migrating and settling here in did not deter her – “could not shake her verve for life”. Her faith in her family and life was dynamic. She came here along with her entire family – “led her entire clan” – without any complaint. She did not lose heart but fought with the new circumstances at new place strongly to stand at her feet once again as sturdily as she was at earlier place, that she had to leave due to partition. She followed her earlier vocation without showing any vacillation in her character – “by simply being and doing” – whatever the new circumstances and life demanded of her – “whatever was required of her to be done”. She neither neglected her duty, nor her responsibility towards her family. It is manifest from the following lines:

Yet all these drastic transitions,

could not shake her verve for life

Amma led her entire clan

with patience and resilience

by simply being and doing

whatever was required to be done (ll. 7-12)

The third stanza,

Amma knew her limitations, often

admitting by saying “I don’t know”,

yet placing her hand on her chest

she would assert confidently:

“The One that is always with me

Have no doubt, That One Knows” (ll. 13-18)

evinces Amma as an ordinary human being knowing well her shortcomings – “knew her limitations”. She wasn’t above other human beings. When she did no know any solution or answer to any family problem, she readily accepted it – “I don’t know”. But she had firm faith in one in whom she firmly believed. She would place her hand on her chest and would assert boldly:

“The One that is always with me

Have no doubt, That One Knows”

She ever maintained that her saviour was always with her and He knows all solutions and answers to her/family problems, therefore, she had no doubt about it. This stanza shows Amma as a staunch believer in her dharma and her Guru or God. She knew well, if she was ever in any problem, her saviour would come to her help.

In the fourth stanza,

Lighting the diya for the daily Aarti

Offering gratitude, seeking fortitude

Amma awould engrave in our ambience

the Principle, that transforms even today

into a blessed and enthralling epoch

each time she walks down my memory lane. (ll. 19-24)

she appears as a religious lady. She would daily light the diya, an earthen lamp, before the Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) in her courtyard while performing her Aarti – prayer. In her prayer, she offered her gratefulness and sought after moral and, perhaps, bodily strength, never to be weak before any act that needed her courage in her family matters, from the source of her faith. The poet tells the readers:

Lighting the diya for the daily Aarti

Offering gratitude, seeking fortitude (ll. 19-20)

Perhaps, by doing so, she wanted to give us a feel and make it permanent in our mind and character that there is some ruling deity, what we call God, the sole Principle of our life. Here, the poet has used “P” to spell principle which suggests the principle of self-reliant life. That principle helped her as long as she lived. Now it stands embedded in the life and psyche of her family members including the persona of the poem. This principle has made their life sanctified and happy even when she is no more. But, whenever, he remembers her at the present hard times of pandemic. The poet puts the idea beautifully in the following lines:

Amma would engrave in our ambience

the Principle, that transforms even today

into a blessed and enthralling epoch

each time she walks down my memory lane. (ll. 21-24)

The last two lines hint at Amma’s “therapeutic response” to the poet when he invoked her wondering “how she would have had handled the uncertainty and tragedy caused by the pandemic Corona” (back cover) in the present pandemic. The other poems of the book need a thorough study to bring out the essence of Amma’s character and what she has bequeathed to her family.

The poet, in this poem, presents Amma as a religious lady who led her family boldly even in the direst circumstances. She never gave in before any trying situations or conditions of life. She had firm faith in her deity of worship and was a bold deriving strength of character from her principles that she also taught to her family members and by which they are ever grateful to her. Thus, this poem serves as initiation to the entire book to be apposite and justifies the title read in the light of the poet’s “therapeutic response” given on the back cover with introduction to him. Amma is the need of every family in the world today!

~*~

The poem, ‘Wanderer’ (p. 91), has twenty lines in five stanzas having four lines each making the stanzas regular. It opens in an ordinary manner alluding to uncertain times. There may be so many reasons about this uncertainty. There is pandemic in the air that has taken a heavy toll of life around the world. No remedy is visible at present. All countries, rich or poor, great or small, developed or underdeveloped, are equally affected. At the top of it, lockdown has been clamped on free movement of people. People are dying without there nears and dears. At times they were being buried, hundreds together, in big pits. In cremation grounds, numbers are allotted for the respective turn. There is neither proper burial, nor cremation. There is so much panic about the disease that even close family members are not allowed to go near their family members. Even medical staff is scared and over-pressed for duty. This has made times not only uncertain but also difficult. There is no surety of life. No medicines, no injections and no vaccines are in sight and that has made life unpredictable. Amid such a chaos in life, human desires are aplenty: whosoever, gets a chance wants to mint money out of this situation; lovers want to love. Cravings have no end. All desires seek their accomplishment. The protagonist tells:

The poem, ‘Wanderer’ (p. 91), has twenty lines in five stanzas having four lines each making the stanzas regular. It opens in an ordinary manner alluding to uncertain times. There may be so many reasons about this uncertainty. There is pandemic in the air that has taken a heavy toll of life around the world. No remedy is visible at present. All countries, rich or poor, great or small, developed or underdeveloped, are equally affected. At the top of it, lockdown has been clamped on free movement of people. People are dying without there nears and dears. At times they were being buried, hundreds together, in big pits. In cremation grounds, numbers are allotted for the respective turn. There is neither proper burial, nor cremation. There is so much panic about the disease that even close family members are not allowed to go near their family members. Even medical staff is scared and over-pressed for duty. This has made times not only uncertain but also difficult. There is no surety of life. No medicines, no injections and no vaccines are in sight and that has made life unpredictable. Amid such a chaos in life, human desires are aplenty: whosoever, gets a chance wants to mint money out of this situation; lovers want to love. Cravings have no end. All desires seek their accomplishment. The protagonist tells:

Times are uncertain

Life unpredictable

yet, desires abound

Seeking fulfilment (ll. 1-4)

The persona, in the second stanza, asks for a day’s time to try his level best “to empty / the trunk of cravings”. These words suggest as if the cravings or desires are material things put in a tin box, bag or sack and it is so heavy that the speaker finds it very hard and heavy to pour out. Can desires be concrete like other objects? Desires are abstract: these may be about concrete things or abstract passions or emotions. The speaker is silent about their nature. He seeks permission of the person to whom he seems talking or the reader. So, he begs:

Allow me to exert

for one more day

in my attempt to empty

the trunk of cravings (ll. 5-8)

The third stanza, leaving aside uncertain times, unpredictable life, and desires talks about a journey. This is not oft repeated journey, but new one. He is very clear about it that it must commence purely and untarnished. He seems aware of the fact that cravings will, for sure, tarnish the journey, which the speaker wants to keep immaculate. There is no language to help the traveller on his journey. The last line of this stanza tells clearly that the protagonist has undertaken or is undertaking this journey “to explore the unknown”. The two words, “explore” and “unknown” throw light on the objective of the speaker. The destination of journey is not known. So, the traveller has to explore himself the ways and means to discover and investigate about this destination. The following lines make it clear:

The new journey

must begin, unsullied,

without any language,

to explore the unknown (ll. 9-12)

In the fourth stanza,

Verily all will belong

to the same Cosmos

yet, let me not wonder

as to who will meet (ll. 13-16)

the persona of the poem tells that he is not the sole traveller. There will also be others, who are also moving toward the same destination and belong to the same cosmos. Here, cosmos implies this world, though used in wider sense connoting universality of the thought. Though the speaker imagines larger number of travellers, yet is not deterred by their presence. This thought does not haunt the speaker and he stays undaunted and confident expressing no surprise that who he comes across on his way.

The last stanza is continuation of the fourth that he is least concerned about who meets him on his way and walks with him on this voyage. Here, the hitherto journey becomes voyage and shows spatial change in the mind of the speaker – from terrestrial to acquatic. He is resolute on his decision about his journey and, instead, prays seeking blissfulness to be sincere to himself. The poet expresses it in the following lines:

walk and wander with me

on the new voyage, instead

I pray, keep me blessed

to be true to my self (ll. 17-20)

Once one has gone through the entire poem, the idea becomes crystal clear. This wanderer is moving on his journey all alone in search of “the unknown” of the third stanza. This unknown is none else than the Supreme one, who has been at the centre of the quest of the mystics right from the beginning of humanity. In his quest, one has to move by oneself. Therefore, this poem is a mystic’s untiring quest to search the identity of “the unknown”, who has ever since the dawn of humanity and spirituality eluded the seekers. But he wants to remain sincere in his exploration of this “unknown” or the source of mystic mind.

Architecture of the Poems:

All the poems are written in free verse stanzas. No figure of speech has been put to service. From construction point of view, all these poems are simple, both in language and construction, but deep in philosophic thought.

‘Solitude’, as earlier shown, has five stanzas. The lines vary in length from two to nine syllables. The poem betrays the monologue form. In ‘Amma’s Gospel’, the narrator describes what Amma says and then, at the end of her speech, the narrator manifests his curiosity, doubt, and finally wants to know if he has understood Amm’s gospel or not with a similar suggestion to the reader . Here, the lines resonate between one and twelve syllables in length. The four stanzas of ‘Amma ji’ are different from the unequal stanzas of the other poems in that these have six lines each and, mostly, the lines are, seemingly, in iambic pentameter, having ten syllables. The five stanzas of ‘Wanderer’ are uniform in length with four lines each though the number of syllables varies between five and seven.

To conclude the argument, the “unknown”, of the ‘Wanderer’ and of ‘Solitude’, when seen from spiritualistic stance seems to coalesce into one and the same to exhibit the poet’s spiritualistic journey carried on all alone, in solitude, necessary to reach the destination or explore the unknown reality that has been at the centre of human quest in all ages throughout human history of mystic contemplation. Amma serves as a representative of the Hindu culture and religiosity of the Sanatana Dharma and a proficient family-leader.

Works Cited

Krishan, Rajender. “Solitude.” Solitude. Cyberwit, India, 1983. and Setu Publications, USA 2020

“Amma’s Gospel” and “Amma ji”. Amma’s Gospel. Setu Publications, USA, 2020.

“Wanderer.” Wanderer. Setu Publications, USA, 2020.

Illustrations by Simi Nallaseth and Niloufer Wadia

|

|

|

01-May-2021

More by : Duni Chand Chambial