Feb 07, 2026

Feb 07, 2026

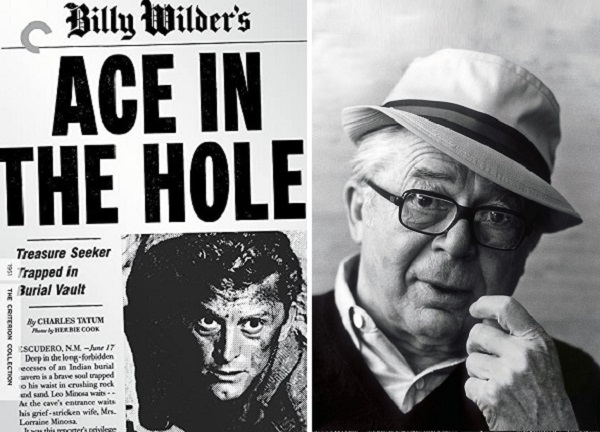

– A searing, visceral commentary on celebrity culture, narcissism and obsession with the self

The great sage Gautam Buddha once presciently observed that life is like dew on a blade of grass; it is strictly a morning phenomenon, transient and short-lived till it is melted by the sun. Ace in the Hole opens with a shot of an empty desert patch, barren and unoccupied, without any human presence. Yet barely a few hours earlier, the whole of mankind was there in attendance, watching intently in an atmosphere resembling a noisy carnival with an admission price to enter, take photographs and souvenirs, have breakfast or lunch, while sweaty workers toil in the sun by the side of a cursed mountain that is a sacred burial ground of the local Indian tribe. The ultimate irony is that a man lies buried in a cave within the mountain, fighting for his life while the circus around him comprising the workers, the onlookers, the reporters, mayor and politicians take centre stage, and the rescue effort becomes secondary, the constant drilling seemingly getting closer to the trapped man Leo Minosa. At the heart of the film is a clearly defined fragility of life and death, the juxtaposition of pain and revelry, fear and exuberance, the plight of a man hours or minutes away from death, while the crowds have endless hours of fun, without any worry. It is a most incongruous but telling scene which captures the absurdity of life.

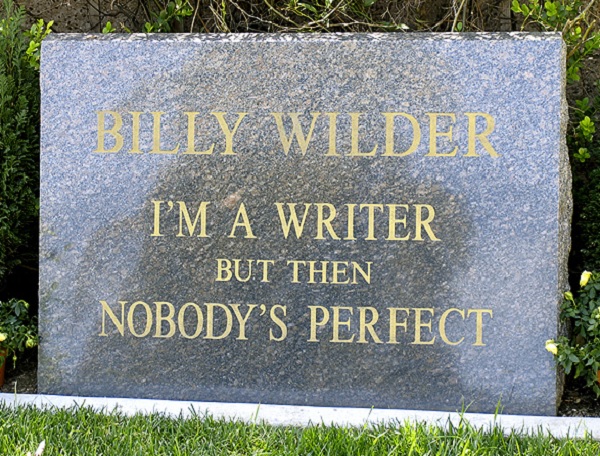

This was Wilder’s first film as producer, director and screenplay writer, but it was a commercial and critical failure. It is uncomfortable viewing due to its cynicism and raw edge; there is little sympathy for the human condition or the characters that appear in the arc of the story. It is as far removed from the usual afternoon or evening cinema fare as it’s possible to be. Everyone is shown in their true light and colours; every fault, quirk, idiosyncrasies and obsessions, are laid bare as if to emphasise the fickle nature of life and how our behaviour changes when we are in the midst of a story or happening that has ramifications for us all. At the film’s core is the obsession with glory, especially individual gratification; a man may die because of this and the seemingly long-winded effort to rescue him, but it is propelled by greed, by the public’s insatiable appetite for the momentary thrill, before we disperse and move on to the next story. Today’s cause celebre is tomorrow’s yawn and bore, but it must be exploited to its maximum potential and widespread exposure.

The film is dominated by Kirk Douglas as the reporter Chuck Tatum, once famous, now discarded and down at heel, passing through the backwaters of New Mexico, with a car in need of repair, reputation in tatters and in need of a job. The newspaper office of the Albuquerque Sun Bulletin is the last place Tatum could end up in, the last refuge of the scoundrel as Voltaire once remarked when discussing patriotism; he is a maverick, a primal force of nature, at home in the big city, in search of scoops, unsavoury characters and the urban jungle teeming with life. The local rattlesnake competition is not Tatum’s metier; it is too bland and banal for his taste, given his thirst for sensationalism, the big story, the Tatum Special. The proprietor offers him a job, even if the paper made Tatum wanting to “throw up” and whose motto is truth, not the embroidered or overwrought version, but the simple, factual statement. The tapestry on the wall behind the secretary’s desk outlines the integrity of the paper, even a local journal like the Bulletin; it may not have the cache of the New York Times or the other East coast heavyweights, but it can’t and won’t deviate from or compromise its ideal. It is quite clear that the paper and its cautious, staid owner will clash with the new recruit with their differing and contrasting views, the old world against the braggadocio and bravado of the new.

On his way to cover the rattlesnake competition, Tatum and his young protégé stumble upon a local man, Leo Minosa, the owner of a petrol station and diner, trapped in a cave in the mountain, regarded as sacred by the local tribe who won’t go near it because it carries the curse of the seven vultures. His mother is praying for him in the backroom, his wife is about to walk away and his father is trying to get some local help; sensing his opportunity, brushing aside the policeman on watch with the defiant snarl – “I am the guy that’s gonna get him out of there” – Tatum goes inside the cave, with his disciple, to reassure Leo of organising his rescue, take some photographs and returns outside. Before his visit, he has a genuine altruistic desire to help Leo and bring him out safely. It seems his view changes once the full impact of the story, the context, the fears of the local tribe, the ancient mountain and its standing within the local community, the opportunity to turn the rescue operation to his own advantage and return to big time, become clear. Driven by greed and aggrandisement, narcissism and an inflated ego, the character of Tatum turns into an unstoppable monster; the main story becomes secondary; it’s the story within and behind the story, of a reporter’s return to prominence and his own by-line, that now becomes prominent and all-encompassing. Everything becomes a tool in the hands of Tatum. When visitors arrive at the site from outside, they don’t come by any train, but the Leo Minosa Express to the tune of a song sung by a balladeer. This descent into lurid showbusiness, with all its trappings and accoutrement, proves fatal.

The film argues that Chuck Tatum is a good and courageous man, who allows his baser instincts to take over his character. His first visit to Leo at the outset, risking considerable danger to himself from dust and falling debris, proves that his motives are genuine and humanitarian; his later visits also show his altruistic and noble intention to lead a rescue mission. Unfortunately, once his self-serving desire manifests himself, there is nothing to stop him, not the other journalists or the dignified owner of the Bulletin; nor Leo’s wife who he forces to play the part of a soon to be a grieving widow and stops from leaving. He taunts and manipulates the journalists, sensing an opportunity to take revenge on them, telling them that “they are in the water, he is in the boat”, when they suggest they are all part of the same fraternity. When Mr Boot,

the paper’s owner, disapproves of the way he is prolonging the story in order to increase the circulation and get himself back into the mainstream, he retorts by using a sporting metaphor: “Look, I’ve waited a long time to get my own back; now that they have pitched me a fat one, I am gonna smack it right out of the ball-park”. Kirk’s delivery of this line is so resonant that it encapsulates a zeitgeist moment: a human life, in the form of a dying man, is a fair game, a sport, a circus and carnival rolled into one, played out in the full glare of the media and the watching spectators, with their caravans and trailers, the obligatory merchandise and gifts. Only the t-shirts and baseball caps are missing.

It is reminiscent of modern life imitating reality television, or is it the other way round? Put people in a given situation, regardless of how absurd or incongruous the setting is, stare into the camera lens and watch the ratings soar. The ultimate irony is that Leo’s life could have been saved, had the salvage crew, instead of drilling from the top of the mountain, gone in from the front and Tatum would have been a true hero and even more famous. Perhaps the curse of the old Indian burial grounds and its spirits disturb Tatum’s vision. Speaking to the editor of a big newspaper from the East, he says he is ready to tell a story, behind the story, of how he allowed a man to die when he could have been saved. By the end, he tells Mr Boot he is a thousand dollars a day newspaper man who can be hired for nothing, walking towards the camera, before collapsing in a heap, in itself a homage to an earlier scene at the beginning of the film.

The film references the true-life story of Floyd Collins who in 1925 became trapped in a cave in southern Kentucky. Fired by the human-interest angle, Tatum decides to exploit the developing Minosa story to his advantage with the aim of winning not only the ultimate literary prize and the accolade that goes with it, but to be acclaimed a hero in the grand tradition of the true American hero. Noble, heroic and courageous, with literary fame and gravitas in the manner of Hemingway or Steinbeck, Chuck Tatum could have been a bona-fide celebrity for both his words and deeds. It takes courage to go inside a cave to rescue a trapped man; but he is never the same afterwards. He is doomed by the lure of the big time as well as the Indian curse and the legend of the seven vultures. The deaths of Floyd Collins and Leo Minosa have been in vain.

Ace in the Hole is a remarkable film, an indictment of and social commentary on society’s thirst for sensationalism, sordidness and tawdry behaviour. It doesn’t hold back and is a bold critique of celebrity, the ephemeral nature of fame, the transient attention of people’s interest, the absence of moral core and the complete disregard of human values. The empty stretch of arid desert earth, dried out by the sun, without vegetation, flowers, trees, birds, animals or water which opens the film, serves as a metaphor for the vacuity of human life.

05-Jun-2021

More by : Kewal Paigankar