Feb 07, 2026

Feb 07, 2026

by Malashri Lal

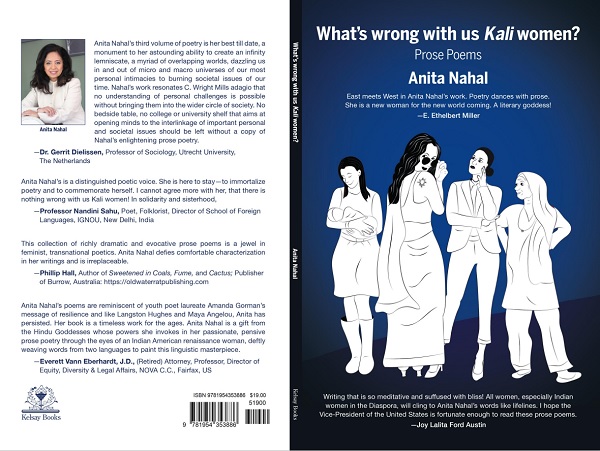

What’s Wrong With us Kaliwomen?

Prose Poems by Anita Nahal, (2021)

Kelsay Books, Utah, USA, pages 90. USD 19.

True to its rhetorical title What’s wrong with us Kali women?, Anita Nahal’s book challenges all stereotypes of womanhood. The goddess Kali, dark, naked, powerful, affirmative destroyer of evil aggression is the presiding figure of the new feminism that Nahal envisages, one that is impatient with platitudes and angry about delays in the delivery of social justice. The context is global though Kali is invoked, because she is transposed as a metaphor for female energy that enters the cause of all the marginalised people whether women, men, transgender, children, coloured, disabled, victims of violence, trampled by patriarchy. The words and images are like magnet. It’s a large sweep, yet the passion of the voice in the sharp vignettes of poetry gathers those harshly cast aside and urges them to rise with confidence in a collective march for justice.

Living in the USA and having worked closely with people of colour, Nahal slides easily from newsroom history to the pages of anguished poetry. “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” Eric Garner said, and this turns into an elegy for the racially brutalized: “Being accused/ Bring lynched. Burned. Chocked. Raped. Extinguished. How easy is it for a black life to be taken.” Class, gender and colour are leitmotifs in Nahal’s poetry—she perceives the markers everywhere despite wearing “Prada tailored suits”, being “the resilient Indian woman”, and seeking the “Tree of Souls”. This volume of poems is a search for the roots of this anguish, the colour based discrimination being the political and social one and its gendered contextualizing taking the narrative to a much deeper level.

The poem, “Fallacy of a single immigrant mom” is perhaps a key to the gap between America’s promise of equality and the actual deliverance of the ideal. Says Nahal, “Single mothering is tough they say…so many societal injunctions…Patriarchal mostly, despite being born in the land of myriad female goddesses. The West is not very different….Recent immigrants around me were buying homes…while I was on a journey to raise a decent human being….I am a single, immigrant, pleased , grateful mom. And that’s no fallacy.” Looking back, it’s clear that the home country, India, was no kinder on a single mom, and the young Anita decided to migrate to what seemed a less discriminatory society in the US. Her poems show the variables in her experience, sometimes joyful liberation in the freedom from a censorious community, sometimes nostalgia for family love in India. The parents are a strong presence in her memory—a protective, affectionate mother, a renowned, intellectual father. Several poems capture the poignancy of periodic visits to see the parents aging and then passing on. In parallel is the creation of a personalized environment in the USA, with her son’s future as the major concern. Acutely observant, reflective and piquant, Anita Nahal’s prose poems are unabashed about the conflicting emotions of “belonging” and “unbelonging” till she finds her primary constituency to be the cause of women, irrespective of the country of their origin or residence.

The “Kali women” are therefore generic, contemporary, strong, questioning. “I am Kali and Parvati, and I’m dark and a goddess too. I can control time. Alter time. I am magnificent, I forgive. I have streaming passion.” Durga, Sita, Draupadi are women who join the pantheon of rebel figures who had to assert their selfhood over and above the position granted to them by society. The cause of the “native Indians” in America and Canada enter this purview as well for Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee is a text that the poet remembers well. “Isn’t equality the only color?” Nahal asks.

In a book published this year, the angst of the pandemic can hardly be ignored. Pertinent allusions of this context and the poet asks if, at last, human beings have been united against a common and invisible enemy. Sadly, “race, religion, gender, plethora of biases still persist”, laments the poet. Invoking the courage of American civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Fanny Lou Hamer, Anita Nahal calls out for the “right to space” for the new woman, on her own terms. “Covid-19’s madness, churning, tossing, whipping” has, unfortunately, shrunk that space, but the poet holds on to hope, and like the eternal mother, to the child she must protect. The child, by now, has become emblematic of the future, the certitude of the triumph of women. With Ma Kali in the lead, can one ever falter?

First published in The Statesman on October 23, 2021

23-Oct-2021

More by : Malashri Lal