Mar 13, 2026

Mar 13, 2026

by Mehru Jaffer

Urban nuns and feminists are challenging the most sexist aspects of Buddhist monasticism in Ladakh, also known as Little Tibet, according to Kim Gutschow, American anthropologist and Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion at Williams College (USA).

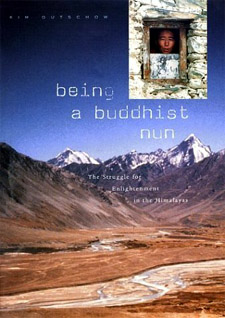

Author of 'Being a Buddhist Nun: The Struggle for Enlightenment in the Himalayas', published by the Harvard University Press, Gutschow first visited this part of the Himalayas in 1989. A bastion of Tibetan Buddhist culture since the 10th century, visitors have been attracted to monasteries in Ladakh but know little about nunneries.

Author of 'Being a Buddhist Nun: The Struggle for Enlightenment in the Himalayas', published by the Harvard University Press, Gutschow first visited this part of the Himalayas in 1989. A bastion of Tibetan Buddhist culture since the 10th century, visitors have been attracted to monasteries in Ladakh but know little about nunneries.

After 16 years of research in the area, Gutschow's conclusion is that Himalayan Buddhist monasticism is no Shangri La. Gender hierarchy endures here, and nuns still toil on land that does not belong to them in exchange for their daily bread while monks are fed liberally from the collective monastic resources.

The idea that nuns can be as capable as monks in attaining liberation is yet to be accepted but the nuns' institutionalized subordination is beginning to be undone through everyday acts of resistance against the patriarchal authority of monks.

A nun told Gutschow that she had heard on the radio that men and women are equal. If Indira Gandhi and Benazir Bhutto could head the governments of their countries, she wondered, then why should women not have the same chance at enlightenment that men do?

The common belief has been that nuns derive their status from association with monks, and from the part they play in enabling monks to divorce themselves from worldly matters. Therefore, equality and independence is not considered an attractive proposition for nuns but rather threatening and confusing to their basic sense of religious identity. In the Tibetan idiom, women continue to be seven lifetimes behind men and therefore cannot gain liberation until they are reborn as men.

However radio, film and television have added to a wider appreciation of gender equality among Buddhists. "The reigning hegemony of monks has been disrupted but centuries of patriarchy cannot be overturned overnight," Gutschow says.

The synergy between Buddhism in Ladakh and feminism dates back to the early 1990s when a group called the Ladakh Women's Alliance was founded by Swedish development expert Helena Norberg-Hodge to counter the negative consequences of development and the increasing participation of Ladakh in the global economy.

Dr Tsering Palmo, a 40-year-old nun, is in the forefront of a new era dawning for Buddhist women who want to become nuns. The Ladakh Nuns Association (LNA) founded by Palmos in 1996, has increased education, visibility and material status of nuns, steering them away from the centuries-old tradition of being exploited as domestic help and field labor.

Under the umbrella of the LNA, nuns from the region now meet regularly to exchange ideas and to address common problems. The most immediate need of the nuns is for adequate residential or assembly space, teachers and more ritual training. The most pressing problem is that nuns enjoy no permanent endowments, forcing most of them to work as domestic or wage laborers rather than devoting themselves to spiritual study.

Palmos described the nuns as "hanging in the middle between two worlds", because they are neither laywomen nor fully able to be nuns. When questioned, the nuns express a desire for more study and monastic discipline despite the fact that once they give up their life of servitude they receive rebukes from the community.

The laypeople are already complaining that nuns are no longer available for domestic chores. There are others who say that withdrawing nuns from rural areas, where a shortage of labor already exists, is disastrous. Many sympathetic to Palmos' message are also fearful of openly subverting the privileges of monks.

But Palmos carries on day after day even when people laugh at her. Palmos was born into an aristocratic family that was devastated when she announced her desire to become a nun.

She tried to study western medicine but the thought of killing animals for research made her become a traditional Tibetan Amchi or doctor. She continues to support nunneries with the help of foreign funding. She envisions a place where nuns can attend teachings or workshops and train to work in a number of fields as maternal health workers, traditional doctors, painters, tailors or handicrafts experts. She wants to see the nunneries become self-sufficient enterprises as well as educational institutes.

Although the office of the highest living Tibetan Buddhist authority had previously ignored Palmos' numerous requests for a meeting with the Dalai Lama, in 1998, he accepted her invitation to talk about women.

The Dalai Lama spoke publicly about the equal capacity of both women and men for enlightenment. The local attitude towards the nuns altered noticeably after the Dalai Lama's speech was highlighted in the local media.

For the first time, a congregation of nuns was invited to perform a ritual in 2001 along with venerated monks. Laywomen were impressed by the nuns' ritual performance but most hesitated about asking nuns to conduct a ritual in their own home.

Ngawang Changchub is one monk who tried to convince local villagers to sell a parcel of wasteland to the nunnery for the construction of a trekking lodge. Local elders, however, balked at the idea of nuns acquiring either landed wealth or power in the local community.

Most monks, too, feel threatened and with good reason: in recent times, the population of resident monks is on the decline and the rising proportion of nuns may be a growing cause for concern among the monastic leadership.

09-Apr-2006

More by : Mehru Jaffer