Feb 07, 2026

Feb 07, 2026

Caste, we all know, is a four-letter word in five letters. No one wants it, but everyone has it. We profess to live without it, but our life forever is guided, mostly misguided, by it. We denounce it when we feel like and swear by it at other times.

But what is Caste in real sense, in the first place, a borrowed term coined by the Portuguese?

“Pride of ancestry, of family and personal position and of religious pre-eminence, which is the general grand characteristic of caste, is not peculiar to India. Nations and peoples, as well as individuals, have in all countries in all ages and at all times been prone to take exaggerated views of their own importance, and to claim for themselves a natural, historical and social superiority in which they have had no adequate title.”

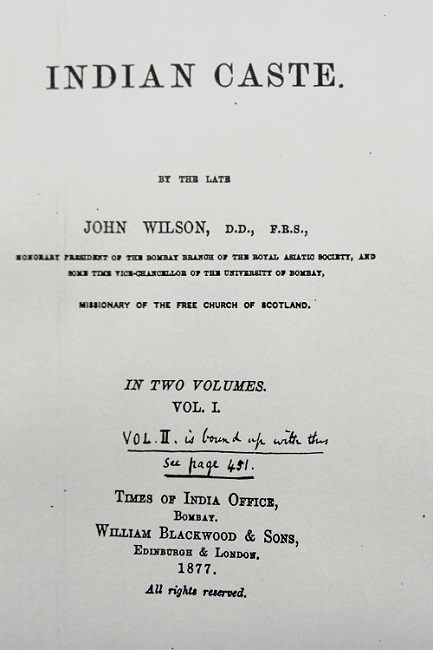

So begins an exhaustive 700-page book titled ‘Indian Caste’ by Dr John Wilson, published in two volumes in 1877, perhaps the first and obviously the most comprehensive treatise on the caste-ridden Indian society of the past, with perhaps some telescopic extension to the present.

Dr Wilson, a one-time Vice Chancellor of the Bombay University, was then president of the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The book, a product of two decades of his research and published two years after his death in 1875, is a veritable treasure trove of information on the Hindu community of the past, their precepts, practices and pretensions and the way in which the upper echelons among them suppressed, often with unparalleled ferocity and viciousness, those down below, especially those in the lowest rung of the society they termed as Shudras.

Pointing out that Herodotus found ancient Egyptians ‘excessively religious beyond any other people’ and addicted to their ancestral customs beyond any other, Dr Wilson said ‘in their multitude, diversity, complication and burdensomeness of their religious and social distinctions the Hindus have left the Egyptians far behind.’

Indian Caste, he said, ‘is the condensation of all the pride, jealousy and tyranny of an ancient and predominant people dealing with the tribes which they subjected, and over which they have ruled, without the sympathies of a recognised common humanity.’

He quoted Manu, the lawgiver, as saying: ‘For the sake of preserving the universe, the Being Supremely Glorious allotted separate duties to those who sprang respectively from his mouth, his arm, his thigh and his foot.’ To Brahmins he allotted the duty of reading the Veda and teaching it, to Kshatriyas to defend the people, to Vaishyas to engage in agriculture and trade and to Shudras to be servile to the other three classes.

According to Dr Wilson, a similar origin and similar duties were ascribed to the four castes in the Shanti Parva of Mahabharata, in the Matsya, Bhagavatha and several other puranas, in Jati-Mala, or Garland of Castes, of Bengal in Jati-Viveka of the west of India, and in the Sahyadri Khanda of Skanda Purana.

With extensive quotes, almost on every page, from Manu and other lawgivers and from the religious texts like the puranas mentioned above, the book makes absorbing reading for anyone interested in the life and times of India’s Hindu society of the distant past. It is at times fascinating, at times intriguing, at times hilarious and at times horrifying, the last when it comes to the extremely ferocious penal provisions prescribed by Manu for the hapless Shudras who transgressed the laws.

One amusing instance of the famed laws of Manu may be found in his injunctions on the marriage of a Brahman (spelling used by Dr Wilson) during the grihasthasrama phase of life. The Brahman has to choose as his wife a girl “whose form has no defect, who has an agreeable name, who walks like a swan or a young elephant......” (While rendering the relevant Manu passage, Sir William Jones had made the bird as adjutant bird and Dr Wilson made it as goose, though the Sanskrit word was hansa or swan.

Dr Wilson finds the caste system as “the offspring of extraordinary exaggeration and mystification, and of all the false speculation and religious scrupulosity of a great country undergoing unwonted processes of degeneration and corruption. It is now the soul as well as the body of Hinduism.”

Tracing the etymology of the word caste and its Indian counterparts like jati and varna, he said gradually these words had come to represent not only race and colour, “but every original hereditary, religious, instituted, conventional distinction that it is possible to imagine.”

And at the top of the caste hierarchy the Brahman has put himself at an exalted position, saying whatever existed in the universe was all in effect the wealth of the Brahman since he was entitled to it all by his primogeniture and eminence of birth. Their argument was like this: “The Brahman was the first born by nature (agrajanma), the twice-born (dwija) by the sacrament of the maunji (poonool), the deity on earth (bhudeva) by his divine status and the intelligent one (vipra), by his innate comprehension.”

And according to the Shasthras, the Brahman was put above every law, even of a moral character whenever it clashes with his worldly interests. Even truth and honesty must be dispensed with for his peculiar advantage.

“The Brahmans, as themselves the great authors of the perceptive parts of Hindu Shasthras, have no feeling of shame whatever in stating their pretensions and urging their prerogatives. Only they must read and interpret the Veda, which they profess to be the highest revelation of the will of god. Their wrath is as dreadful as that of the gods in heaven.”

Dr Wilson referred to a common syllogism made popular in his times by the Brahmans:

The whole world is under the power of the gods,

The gods are under the power of the mantras,

The mantras are under the power of the Brahman,

The Brahman is therefore our God.

“These fabrications, which appear to be ridiculous, were intended to secure to the Brahmans veneration and awe,” he said. An endeavour also has been made in the Shasthras to secure to them their lives. They must not be killed for even for the most enormous offences.

Dr Wilson also refers to the inhuman treatment meted out to the Shudras even for minor transgressions and the fiendish forms of punishment prescribed for them. “A once-born man, who insults the twice-born with gross invectives ought to have his tongue slit; if he mentions their name and class with contumely, an iron style ten fingers long shall be thrust red hot into his mouth; should he through pride give instructions to priests concerning their duty, let the king order some hot oil to be dropped into his mouth and ear. If he places himself on a seat with the highest, a gash is to be made on his buttock, if he spits on him with pride, the king shall order both his lips to be gashed......”(Manu VIII.270-272)

While the punishments for the Shudras were unimaginably harsh, many might point out that most of the ancient civilisations had similar inhuman penal methods, including burning live at the stake, crucifixion, dismembering and branding. Perhaps the intensity of the penal acts in the Hindu shasthras was much more than elsewhere.

Dr Wilson quoted Manu to point out the kind of exclusion faced by Shudras. “The Veda is never to be read in the presence of a Shudra“ (Manu IV.99). “He has no business with solemn rites (Manu XI.13). Manu equates the murder of a Shudra by a Brahman to the killing of a cat, an ichneumon (a kind of wasp), a bird, a frog, a dog, a lizard, an owl or a crow as the penance prescribed is the same (Manu XI.131).

While looking down upon these aspects of the Hindu shasthras that made mincemeat of human elements when it came to dealing with the Shudras, Dr Wilson had a word of appreciation for the Brahmans for the way in which they observed their austerities.”Along with these enormous faults,” he said, “it is but fair to look at the strict discipline, continuous ceremoniousness and rigid austerities it has prescribed for its activities.”

He then went on to explain the severe regimen that the Brahman was expected to observe during his progress from Brahmacharya to Grihastha to Vanaprastha to Sanyasa. Is it possible to strictly adhere to it all along? “I have a strong impression on my mind that a great deal of the Brahmanical legislation was, from the first, intended only for effect and that it was never designed to be carried into execution as far as the priestly practice itself was concerned,” he said.

The most noteworthy argument put forward by Dr Wilson was that the obnoxious system of caste observed in the Hindu society had no sanction of the Vedas.

“Caste in the sense that it exists in the present day, we are more and more persuaded, was altogether unknown among the ancient Aryas, though doubtless like other consociated peoples they had varieties of rank and order and occupation in their community.”

Dr Wilson said the opinion of Dr Max Muller, the editor of Rig Veda and the most competent judge in the case, was entirely in accordance with that which he had ventured to express.

In an article published in The Times, London, on 10th of April 1858, Dr Muller said:

“Does Caste as we find in Manu, and at the present day, form part of the religious teaching of the Vedas? We answer with a decided ‘No.’

“There is no authority whatever in the Veda for the complicated system of castes, no authority for the offensive privileges claimed by the Brahmans, no authority for the degraded position of the Shudras.

“There is no law to prohibit the different classes of people from living together; from eating and drinking together; no law to prohibit the marriage of people belonging to different castes; no law to brand the offspring of such m marriages with an indelible stigma.

“All that is found in the Veda, at least in the most ancient portion of it – the Hymns – is a verse in which it is said that the four castes, the priest, the warrior, the husbandsman and the serf, sprang all alike from Brahma.

“Europeans are able to show that even this verse [Purusha Sooktha] is of later origin than the great mass of the Hymns,”.

Indian society has come a long way away from the times described by Dr Wilson one and a half centuries ago. But Caste and Manu are still around. The intensity of the deprivation faced by some sections may not be as great as in the past, but from the four original classes, Caste, for all practical purposes, has proliferated to many more, including, perhaps, to other religions through conversion.

Caste is still now a symbol of personal pride or social stigma, as the case may be, even when being a great political possibility and a business proposition. In spite of yeomen efforts by many people across the nation, like the great social reformer from Kerala Sree Narayana Guru whose 168th birth anniversary fell on 31 August, 2023, casteism and its bigger cousin religious bigotry are ever on the rise.

As long as we are bound by law to mention our caste and religion in every official record, in every educational institution, in fact everything in man’s long journey from birth to death, caste cannot be cast away from our psyche.

02-Sep-2023

More by : P. Ravindran Nayar