Apr 30, 2025

Apr 30, 2025

A couple of months back I had the honor of making a presentation to the faculty and students at a university on the topic: Values and Ethics: Revisiting Indian Knowledge System.

As I hurriedly concluded my presentation drawing the attention of the audience to a verse from Yajurveda, “… may we look on one another with the eye of a friend” (xxvi-18), a young lady from the front row of the auditorium posed a question: “some people, for no valid reason, shout at you and you can’t give them back, but it causes a lot of stress. How to handle that stress? Am I to simply accept it? But it causes a lot of stress … a lot of stress.”

I could see the pain of it writ large in her face. I did respond to her question, though hurriedly. Nevertheless, we shall now examine it in detail.

First things first: Let us understand what stress is. Stress is the body’s response to a stressor. A stressor is a trigger that may cause one to experience physical, emotional, or mental distress and pressure. In the instant case, the stressor is: the uncivilized behavior of the person who yelled at the lady for no valid reason. This rude behavior triggered a feeling of being overwhelmed and she could not cope with the pressures caused by it.

Our thoughts influence our emotions.

Emotions influence hormonal secretions and our behavior.

A stressful situation triggers a cascade of stress hormones which produce well-orchestrated physiological changes in our body. A stressful incident makes the heart pound and breathing quicken. Muscles tense up. Beads of sweat appear.

This kind of reaction to a stressful event is also known as the “fight-or-flight” response. For, it evolved as a survival mechanism. It enables people to react quickly to life-threatening situations—activates one to fight the threat off or flee to safety.

Unfortunately, there is a flip side to it: the body can also overreact to stressors that are not life-threatening, such as the one incident faced by the lady in reference, yelling of somebody at you, traffic jams, deadlines at work, etc.

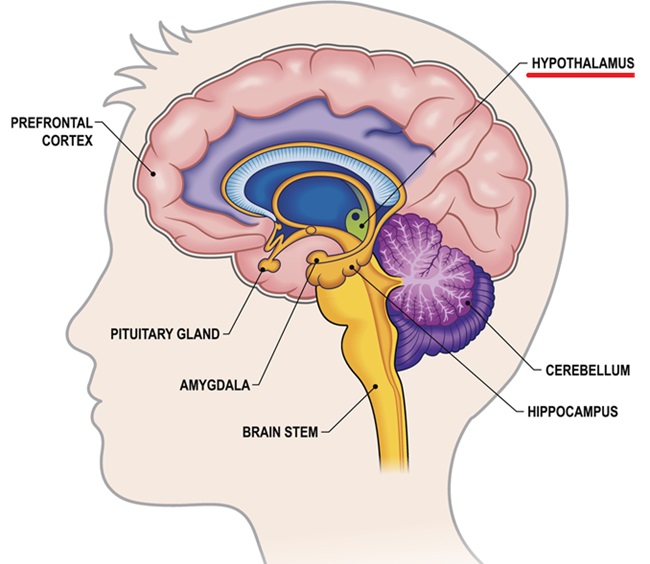

Over the years, researchers have learned how and why these reactions occur. When a person encounters a threat, say noticed a cobra on the path, the eyes send the information to the amygdala—the part of the brain that handles emotional processing. Interpreting the images and perceiving them as dangerous, amygdala instantly sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus.

In turn, the hypothalamus communicates the threat to the rest of the body through the autonomic nervous system, which consists of two components: One, sympathetic nervous system that functions as a gas pedal in a car, and two, parasympathetic nervous system that functions as a break.

On receipt of a message from the hypothalamus, sympathetic nervous system triggers a fight or flight response to the perceived threat by providing a burst of energy to the body. Once the threat is passed, parasympathetic nervous system calms the body by promoting a “rest and digest” response.

On receipt of a distress signal through sympathetic nervous system, adrenal glands also get activated. They respond by pumping the hormone epinephrine into the bloodstream. The circulation of epinephrine in the body brings several physiological changes: heart beats faster, pulse rate and blood pressure go up. Breathing becomes more rapid. Epinephrine also triggers the release of sugar into the bloodstream. All these changes happen so fast that without being aware of them, we even jump out of the path of the cobra well before we realize what we are doing.

Once the surge of epinephrine subsides, the hypothalamus activates the second channel of the response system: HPA axis. It consists of hypothalamus, pituitary gland and adrenal gland. This axis aids the brain to keep the ‘gas pedal’ pressed down. In the event of brain continuing to perceive the threat, hypothalamus releases corticotropin-release hormone. Travelling to the pituitary gland, it will trigger the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone. This, in turn, travels to adrenal glands and nudges them to release cortisol. Thus, the body remains on high alert.

Once the threat passes, cortisol levels fall, and the parasympathetic nervous system applies brake and dampens the stress response. But many people fail to apply brakes on stress. This leads to chronic low levels of stress, which is likely to cause health problems at a later date. Persistent release of epinephrine damages blood vessels. It also increases blood pressure. In turn, the risk of heart attacks or strokes stand enhanced. Increased levels of cortisol may also lead to overweight.

Fortunately, we can learn the techniques for managing stress responses. Psychologists say that stress is produced not by events themselves but by one’s reaction to events (stressors). It is precisely because of this that we see people reacting to a given stressor differently.

For instance, let us take the lady’s problem of somebody yelling at her for her no-fault as an example and see how two people react to the same problem differently. The man who gives the least importance to such yelling believing that it was the habit of the yeller (ye tho pagal hai, aise chillata hai) and deserves no attention, simply walks away from it. On the other hand, the man who takes it as a personal insult cannot but brood over it: “Of all the people why to me? I behave so soberly, never tread on others’ toes, I speak so gently, and yet why did this man yell at me? That too, in front of so many?” If you keep on agonizing like that over what had happened for days together, your hypothalamus will keep HPA axis active —‘the gas pedal’ remains pressed down for long. It means, release of hormones into bloodstream continuously, which in turn, keeps the body on high alert. This results in chronic stress that can later lead to cardiovascular problems.

Instead, realizing the fact that it is our thoughts that influence our emotions, and it is these emotions that influence hormonal secretions and our behavior, if we could reframe our thoughts about the stressor—rude behavior/yelling, etc.—we can certainly help ourselves in reducing feelings of stress.

Suppose in the instant case, if we could think of the yeller as a man with no culture and hence his yelling merits no cognizance, we may be able to walk out of the incident coolly. We can thus manage the stress emanating from the scene appreciably.

Research indicates that such cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) works better in managing stress. This technique is not limited to the present case alone: whenever you feel yourself spiraling into worst-case scenarios, you better switch your mind elsewhere. Or stay connected with people who can provide you emotional support by listening to you empathetically. Such diversions are likely to relieve you from the overwhelming stress.

It is in order here to quote what lord Krishna said in Gita: “Yah sarvatraa nabhisnehahs, tat-tat praapya subhaasubham, / naa bhinandati na dvesti, tasya prajnaa pratisthitaa (2.57)—He who is without affection on any side, who does not rejoice or loathe as he obtains good or evil, his intelligence is firmly set”. Such a man is termed by him as a Sthitaprajna. A Sthitaprajna is not disturbed by the touches of outward things. He does not rejoice over good (adoration from a colleague/boss), nor lament at the bad (yelling of a stranger/boss). So, his/her prajna — intelligence remains stable. A stable mind can rationally analyse a given situation and wisely steer out of it with the least stress.

We may have to therefore cultivate the state of being Vita-raaga-bhaya-krodhah—free from attachment, fear and anger (Gita 2.56)—as CBT for managing stress. Are you wondering: Easier said than done? But then, is there any alternative remedy?

Images (c) istock.com

10-Dec-2023

More by : Gollamudi Radha Krishna Murty