Jan 19, 2026

Jan 19, 2026

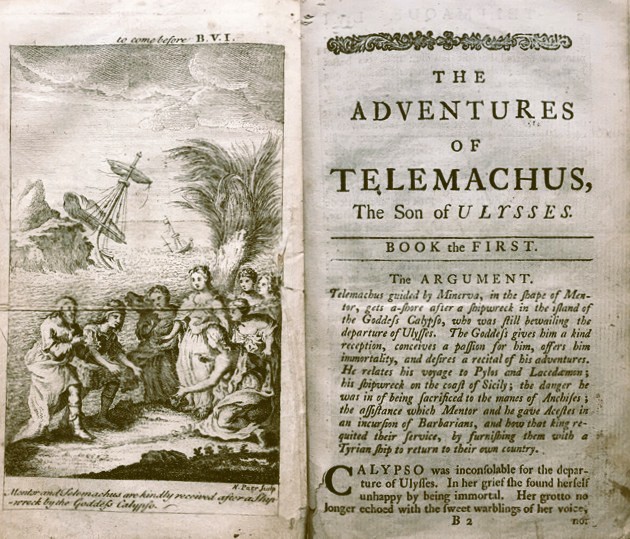

The Adventures of Telemachus.

At the outset of this series of Age of Enlightenment, we had mentioned three very important books in order to know the length and breadth of the social turmoil in the 18th century France. They are Fenelon’s Les Aventures de Télémaque (Adventures of Telemachus), which sets the base for the enlightenment, Montesquieu's Lettres Persanes (Persian Letters), which records the end of Louis XIV’s reign, and Memoirs (Memories) of the Duke de Saint-Simon, who records the minute details of Louis XIV’s reign. In this session let us get to know the first one, that is Fenelon’s Les Aventures de Télémaque (Adventures of Telemachus).

Born in 1651 and died in 1715, Fénelon was not at all destined to write novels. He was first and foremost a man of the church and at the end of the seventeenth century, men of the church were not supposed to write novels, a genre deemed morally dubious. A man of the church like him with high intellectual quality whose interests logically should run toward theology, mysticism, philosophy, politics, and education. Of course, he dabbled in it but while educating The Duke of Burgundy he entered the field of literature.

At the age of 38, Fénelon became tutor to the Duke of Burgundy, the future King of France, the grandson of Louis XIV. And it was for his student that Fénelon began writing a series of educational fictions, such as fables and dialogues of the dead, featuring famous figures. The crowning achievement of this educational endeavor through fiction is a text titled The Adventures of Telemachus, probably written between 1694 and the following years. It was first published without Fénelon's knowledge in 1699, when Fénelon, who had displeased Louis XIV, was already demoted as a bishop of Cambrai. It was published without his knowledge because Fénelon was deeply opposed to Louis XIV's prestige policy for war, and through this fiction, he came out in favor of the superiority of a truly Christian policy based on peace, agriculture, and trade.

Fénelon's book is written as a story that fits into the gap between the fourth and tenth cantos of Homer’s Odyssey. In Homer’s version, Telemachus, the son of Odysseus, goes looking for his missing father at the end of the fourth canto. Odysseus finally returns home in the tenth canto. Fénelon imagines what happens in between—this imagined story becomes The Adventures of Telemachus.

In this fictional gap, Telemachus, guided by the wise Mentor (who is actually the goddess Athena in disguise), travels to various lands, meets different rulers, and learns valuable lessons. Through these adventures, the story shows both good and bad examples of leadership. It teaches what makes a just and wise ruler, and warns against common dangers like pride, poor judgment, and uncontrolled emotions.

It is rather illogical to think that this great classic is primarily a book intended for the education of a single individual. Before Fénelon, there was a whole tradition of educational treatises and texts for the education of sovereigns. The future king must be initiated into the beauties of classical culture and its ancient references. He must receive political concepts drawn from famous examples. He must meditate on the duties of his office. This tradition is absent in Fénelon’s classic.

Fénelon explores stories from Greek and Latin mythology, drawing many references not just from Homer, but also from Virgil and Ovid. His writing is filled with quotes and nods to classical literature—so many that listing them all would be overwhelming. Yet, despite being made up of these ancient references, the story feels smooth and natural. It's carefully crafted, like the grand mythological decorations at the Palace of Versailles, sharing a similar artistic style.

More importantly, the story is also a lesson in politics and moral philosophy. As Telemachus and his guide Mentor travel, they meet kings who are ruled by ambition, bad advice, or uncontrolled emotions. These encounters show the dangers of poor leadership. They also visit peaceful and prosperous lands where wise rulers support trade and farming—examples of good government.

At the end of the book, Telemachus watches as Mentor reforms the kingdom of Salento. Mentor ends the wars with neighboring lands, stops wasting money on luxury, and focuses on helping farmers and promoting useful skills. This experience teaches Telemachus how to be a good ruler when he eventually leads Ithaca. At the same time, the book was meant to teach the young Duke of Burgundy how to rule wisely, since he was expected to become the future King of France.

This book was quite unusual for its time. Many writers would later try to copy it, but there wasn’t really anything like it before. When it was first published, people didn’t know how to describe it. Some admired its beautiful language and poetic style, while others, like the church leader Bossuet, criticized it—thinking it wasn’t appropriate for a religious man like Fénelon to write such a book. The book clearly draws on ancient epics, but also includes features from other genres like fables, pastoral stories, and early novels.

Back then, calling it a "novel" would have been negative, because novels were often seen as lesser literature. Also, traditional novels were mostly love stories told in prose. Fénelon’s book is fiction in prose, but love isn’t the main focus—though it’s touched on, since the young hero is also warned about the dangers of falling too deeply in love.

In the end, Fénelon created a new kind of story by combining different styles—what we might now call an “educational novel.” It was also the first major work to question King Louis XIV’s rule, even though his reign hadn’t ended yet. The book celebrates France’s cultural greatness at the time, but also points out the problems—such as the economic crisis caused by war and luxury, and the harsh power of absolute monarchy. Later, during the Enlightenment, readers embraced the book’s values, even if they didn’t focus on its Christian message. Télémaque quickly became a classic that was widely read, quoted, copied, and even parodied throughout the 18th century.

10-May-2025

More by : Dr. Satish Bendigiri