Jan 18, 2026

Jan 18, 2026

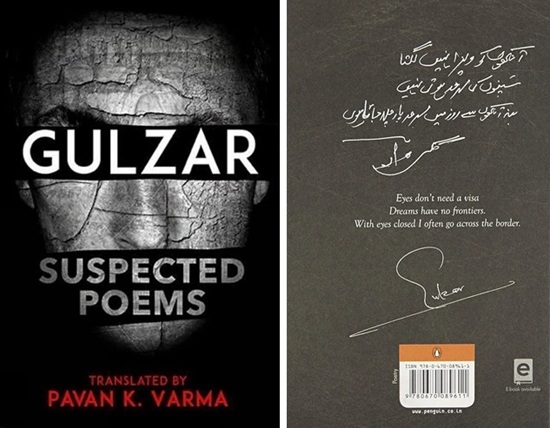

Suspected Poems by Gulzar, translated by Pawan K. Varma, Penguin Random House India, Gurgaon (Haryana), India, Pages 135, Price Rs 299.

The title of Gulzar’s most recent collection of poems, Suspected Poems, translated from the original Hindi/Hindustani by Pawan K. Varma, is quite intriguing. The first impression on a reader's mind is that these poems contain censorious, offensive, and unacceptable material, but after reading the poems, one sits down and mulls over some of the murky aspects of India's socio-political system that are otherwise shining through our politicians' rigmaroles. The poet in Gulzar brusquely turns away from romance to stark realism of the day. He brings to light the acerbities of the current state of affairs in the country in a matter-of-fact tone, of course with the unusual ingenuity of his metaphors and wizardry of words. These new poems reveal the poet’s conflict with hypocrisy, egotism and nonchalance of people in the present-day society. The present-day world is fraught with such ethico-moral confusion and nuisance that speaking the truth and being forthright is always at risk, and hence the title of the book is pertinent to that eventuality.

In this collection of 52 poems, both in Hindi and English, spread over 135 pages, we find moving, picturesque descriptions of certain harsh realities of the present-day Indian society. These poetic snippets bear scathing commentaries on issues of social injustice, crime, atrocity, oppression, exploitation, indifference and egotism prevailing in the country. Seemingly, these short pieces are journalistic accounts of social and political scenario, interspersed with the poet’s remarks, ranging from sly sarcasm and satire to evident ire on several contemporaneous issues of (de)privation, indifference and discrimination. Gulzar finds monotony in everyday news, as no substantial transformation is discernible anywhere in the country: “It has been happening for fifty years / It has happened again! / As though time has put a paan in his mouth / And continues to chew it!” — (p. 11). He refers to the long-stretched problems of terrorism, floods, poverty and starvation accompanied by apathy of the government as well as the media: “These new pictures we saw even then / When there was no camera / This latest news / Must be consumed today and forgotten.” — (p. 11).

The poet in Gulzar frequently interlaces the past and the present of the country to recount the continual strife of the helpless and powerless commonalty against the non-concern of those at the helm of affairs. In “Newspaper”, one can see him raking up the horrid times of the riots of 1984: “The Passport Commissioner looked up... / ‘Any identification that cannot be erased?’ / The Sikh thought for a few minutes / And then suddenly took off his shirt: / ‘There is a burn mark, Sirji, / From ’84. / This can’t be erased!’ — (p. 15). The dreariness of the news media amplifies the angst of the poet: “How long can one munch / The chewing gum of daily statements? / Now one has come to learn: / Just spit it out / If the mouth can take no more.” — (p. 17).

Gulzar expresses his righteous anger at the sorry state of affairs in New Delhi, where the ruling and opposition parties engage in a war of words and nothing substantive ever transpires. In the name of so-called freedom and democracy, the lawmakers of the country are actually betraying the trust of the people who have elected them into power:

There’s nothing new in New Delhi

Except that every five years a new government comes in

And converts old issues to new schemes...

Opening scabbards anew

They unsheathe again all the rusted laws

That can cut neither grass, nor necks! — (p. 3)

In “Shall We Talk about the Country”, the poet refers to the historical wrongs, inhumane wars, cold-blooded massacres, foolish decisions, pointless divisions and partition blues, but he is not specific. He paints a bleak picture of India's past in abstract terms, as if nothing good has ever happened on this land; as if no dream has ever come true; as if no hope has ever been realised. In his desperate craving for a kind of utopia, he becomes pessimistic:

Hopes that drowned in whirlpools again and again

Hopes, panting like wind in the sails

Hopes and wants, murdered and looted

Shall we talk about them again?...

But how can we talk of a paradise

That is not yet in sight? — (pp. 6-7)

In “26th January”, we see an ironic image of a poor, polio-infected boy who is selling tricolour paper flags at the signal with fervour and hope: “‘Two rupees for this tricolour, it’s Public Day / Take one Seth, good for the country.’” — (p. 9). The contrast between the affluent and the deprived here arouses pity for the helpless and hapless child. “Two Lakh Rupees” contains a carping remark about the paltry compensations paid by the authorities to the families of the poor who die in riots or disasters:

If he knew that on his death

His family would get two lakhs

That his death is priced so high

He would have died for himself! — (p. 35)

In “Shroud”, dedicated to Madhav and Ghesu in Munshi Premchand’s popular story, “Kafan”, the poet expresses his inner rage at the sight of extreme poverty and starvation in the country, particularly against the hypocrisy displayed in the name of religious rites and philanthropy:

You are always worried about hunger;

Why sorry, there will be enough leftovers

At the ghat where they serve food as ritual

When dead bodies are burnt on the pyre. — (p. 43)

The following lines from the same poem, however, sounds derisive to the historical-cultural glory of India, famed as the Golden Bird: “What is there to be ashamed of in poverty? / Poverty is older than our culture!” — (p. 43). At the same time, the poet also emphasises the worth of hard work and perspiration for the poor to make ends meet:

Just cut from somewhere a piece of sunlight

And stitch another patch to your garment

It will look like gold thread. — (p. 43)

“Traffic Jam” draws our attention to the daily chaos on all major roads across the country: “For seventy years I am caught in a traffic jam... / No one moves ahead, or steps aside.” — (p. 23). The human traffic is growing day by day and people are getting lost in the crowd. There isn't anyone to mourn this loss: “His hand has slipped from my grasp / He is lost in the multitudes of this town / The search is on for the common man / A search for a person missing!” — (p. 21). Indeed, the common man has no right to be heard anywhere: “When he coughs, words fly around from his mouth... / Someone had asked him for his views / And then cut off his tongue!” — (p. 29).

Today, India's commonalty is divided into several small groups, posing a significant threat to the country's integration. “The Wind Has Changed” depicts how the splintered groups hold their separate flags on the streets with their subjective agenda: “There is a change in the vision of the people / Fists are waving in the wind; / ... / The wind is blowing in a new direction / New flags have started appearing.” — (p. 27). The personified wind signifies the franticness of some revolutionary change at the democratic hustings: “That’s what happens when flags flutter in the wind―/ The wind too flutters, clasping the flag!” — (p. 27).

The poet acts as the spokesperson of the ordinary masses who have a slew of problems to be solved, but they are sucked into the verbal vortex of the politicians’ false promises and convoluted logic: “I came back / Confused, who would solve whose problems!” — (p. 59). The poem “Jalsa” is a hard-hitting pasquinade on Indian politicians’ usual oration, “lengthier than the GT Road”, which is attended by the ordinary masses, “A veritable mandi of those with nothing to do” — (p. 51). The poet reacts to it: “you and I have two histories, both apart. / ... / I am hungry, let’s bring this jalsa to an end!” — (p. 53). “This Useless Grass”, reminiscent of Walt Whitman’s grass symbolism in Leaves of Grass, tells how the common people, despite their ghastly circumstances, survive like blades of grass with a steadfast will to live on: “This meaningless, senseless and stubborn grass / It begins to grow from even the tiniest crevice it can find / In a rock.” — (p. 61).

Gulzar also addresses even the highly combustible issues of religion and caste. “Babri” derides the protest of two factions on useless, barren piece of land, which is today inhabited by “Families of vultures... / Amidst the heaps of garbage lying around” — (p. 63). The contrastive imagery draws a parallel between the two belligerent groups of people pitted against each other for a daft claim:

As the animals of dusk

Fight for every bone of rotting limbs

Whoever can sink their teeth in first

Has the right over that piece of flesh.

Who was the one who struck the first blow of the axe?

Yes, this indeed is that piece of land

Which till yesterday was also a home to some god!” — (p. 63)

The partition of India has been a recurring theme in most of Gulzar’s writings: it is prominent in his collection of short stories, Raavi Paar and Other Stories, and runs through many of his poems. He seems to be miffed over irretrievable human loss that was incurred as a consequence of the reckless political decision based on the ‘two-nation theory’. In “Kabaddi”, he proposes a poetic — (re)solution to problems from both sides of the ‘line of control’ between India and Pakistan: “If the border lines are there, let them be / ... / Let’s use them now as dividing lines for a game... / Come, let’s play kabaddi!” — (p. 75). Even though it sounds puerile, it seems to work with the uncorrupted, crystal-clear spirit of a child as a means to fix the historical blunder committed by our leaders.

Through Suspected Poems, Gulzar emerges as an egalitarian, a democrat, a socialist, a libertarian, a communist, a dalitist and a humanist―all rolled in one. The various socio-political issues and ‘isms’ are more pronounced than verse or genuine poetic stuff, which is quite the converse of the highly imaginative-lyrical use of words what Gulzar is distinguished for. He has taken a sudden departure from the romantic lyricism of his early poetic/artistic career. As an affiliate of the Progressive Writers' Movement, he expressed his leftist leanings through criticism of Indian politics in both fiction and films. His film "Aandhi" was temporarily banned for disparaging then-Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's decision to impose an emergency in the country. In “Half a Rupee: Stories”, Gulzar addressed the volatile issues of insurgency, naxalism, riots and hostilities prevailing in some parts of the country.

No doubt, the professedly “suspected” poems document the real-world issues, but these are still humdrum everyday news, a bit incongruous with verse―sans promise of mental reprieve and/or aesthetic delight one expects from poetry. The saving grace is Gulzar’s exceptional way with words. However, the original Urdu compositions have more verbal felicity than their English renderings. The translator’s work is sincere enough, but at times, it appears that he is at the mercy of words when dealing with typical Urdu phraseology that has no equivalent or appropriate expression in English. The words and phrases such as ‘shagun’, ‘maamool’, ‘supaari’, ‘mansoobe’, ‘zung-aalooda’, ‘baadbaanon mein’, ‘falak’, ‘kalle mein’, ‘muntaqil’, ‘zaeef’, ‘vaadon ke luqme’, ‘zarda’, ‘qimam’, ‘khosha-e-gandam’, ‘aqeede’, ‘choli’, ‘tahzeeb’, ‘behis’, ‘laa-matnaahi taaqat’ do not glow as much in English translation as they do in their original forms in Urdu. Some translations fall short of capturing the impact of the original phrases' figurative, rhythmic, and stylistic aspects and patterns, as well as specific shades of meaning. Besides, the Devanagari script used in the book needs scrupulous editing for spelling and diacritical marks for Hindi and Urdu words.

Overall, while these poems may not be easy on the eye/ear or appealing to the heart, they are thought-provoking and call for the attention of the government, media and the general public to certain fundamental issues of human concern.

24-May-2025

More by : Dr. Kanwar Dinesh Singh