Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

Remembrances of a Sordid Past in Kerala Journalism

The ISRO Espionage Case, a fake case hatched, nurtured and played out to its full malignant potential during the mid 1990s by the police and a section of the press, shredding reputations and affecting brilliant careers, even pulling down a government, will no doubt remain forever as a blot on the collective psyche of Kerala.

Remembering that concocted case itself would cause uneasiness not only to its many victims, who included two Maldivian women and two Indian space scientists, but also to all the people of the times who watched the developments from the sidelines and saw how a perfect non-event was carefully groomed by some wayward policemen and some not-so-guiltless pressmen to become Kerala’s biggest scandal of the century.

Nearly three decades after the Supreme Court of India struck it down as a totally fabricated case, a new book has come out, giving a graphic brick-by-brick account of the buildup of that whole edifice of malignity. And it is written by a prominent journalist, John Mundakkayam, whose paper Malayala Manorama and who himself did extensive and intensive coverage of the events related to the case.

Nearly three decades after the Supreme Court of India struck it down as a totally fabricated case, a new book has come out, giving a graphic brick-by-brick account of the buildup of that whole edifice of malignity. And it is written by a prominent journalist, John Mundakkayam, whose paper Malayala Manorama and who himself did extensive and intensive coverage of the events related to the case.

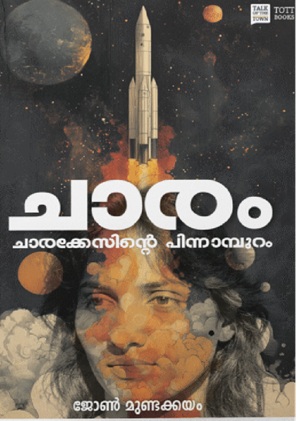

The book is titled ‘Chaaram,’ with a pun on that Malayalam word. Chaaram means Ashes, while Chaaran means Spy. The book’s sub-title is ‘Chaarakkesinte Pinnampuram,’ meaning the ‘Background of the Espionage Case.’

One question that may nag a reader is ‘Why this book now?’ after the whole case has become ‘ashes’ long ago, as the author himself has admitted through the title.

Is it to set the record straight? But the record has been set straight by the Supreme Court in 1998 itself, describing the case as totally fabricated.

Is it then to salvage anyone’s reputation? But no book is sufficient to salvage the shredded reputations of the two hapless women (one of whom is no more) and two hapless space scientists, one of them Nambi Narayanan, then head of the Cryogenic Engine Division of ISRO. All of them were subjected to prolonged and intense physical torture and mental trauma by the investigating policemen and calumny of the worst order by a section of the newspapers.

Is it to apologise to them for the wrong done by way of malicious reporting? But there is not a single word of apology in the whole book.

What then is the real purpose of the author in writing this book? To exculpate himself and his newspaper, at least partly, from the blame of malicious reporting and point the finger at others in a blame game? Perhaps yes.

What strikes one at the first look at the book is its cover: An ignited rocket, gushing out fumes below, with the sad visage of a woman, obviously Mariam Rasheeda, almost camouflaged by those fumes. Sad indeed.

After the spy stories spun by the newspapers and the police were rubbished by the Supreme Court, after she and other accused were fully exonerated by the court, was it proper, and ethical, to put her picture as a still glowing espionage ember in the ashes?

How good and proper it would have been if, instead of her picture, the book’s sub-title just said: ‘Sorry, Mariam.’

But we can find that word nowhere in the book, neither on the cover nor anywhere inside. No one is sorry. And no need for apology.

There is just a reiteration of all the unsubstantiated accusations made against them when the case was in full swing, all in the form of a backgrounder or timeline.

This is in direct contrast with the remarkable ending of R Madhavan’s film on Nambi Narayanan, titled ‘Rocketry,’ which is highlighted by its apology part.

The film ends with the real Nambi Narayanan making a brief appearance in a television interview by Tamil film star Surya. Overwhelmed by what all he heard from the scientist of his harrowing experience in the captivity of the police, Surya, saying he actually does not know how competent he is in doing so, offers to make an apology on behalf of the people “for the way we treated you, for all the due honours we did not shower on you.”

Unfortunately, no such finesse with this book.

The book no doubt makes absorbing reading as it provides an excellent narrative on how an insignificant issue relating to visa overstay by a Maldivian woman was taken forward by a local policeman with a motive. From then on many dramatis personae, from local police, Special Branch and IB, entered the scene, but each of them apparently came with a targeted mission and an action plan. Perhaps each fitting Coleridge’s description of Shakespeare’s Iago, “Motive-hunting of a motiveless malignity.” And with more inputs from more and more motive hunters, the story grew, like an acorn growing into a gigantic oak tree.

The most important offshoot of the non-existent spy story, from the journalistic point of view, was the nefarious nexus between the police and a section of the press. It was in a way a symbiotic relationship, each feeding the other with falsehood masqueraded as the truth and nothing but the truth.

This give and take was soon found insufficient by some newspapers engaged in their unending circulation wars with others. So one of them despatched its reporter to Maldives to dig up nuggets of information on the woman, her family and neighbourhood.

The other newspapers were aghast. And to outdo the James Bond of the first newspaper, two other dailies soon sent their own bureau versions of Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot to Maldives.

These journos definitely did not have any licence to kill as the celebrated film hero James Bond had. But on their return from Maldives their managements appeared to have given them a free hand to kill reputations. And they did it with abandon as their many sleazy features on their Maldivian sojourn reveal. (One Malayala Manorama report for instance had this near-banner title: Maali Theruvile Kamukimaar --The Sweethearts of Maali Streets-- with a picture of a group of girls close to Mariam Rasheeda and half a page of salacious writing).

All these reports, like the long series of features titled ‘Mariam Thurannu Vitta Bhootham’ (The Genie Let Loose by Mariam), which show Malayalam journalism at its lowest ebb, are well preserved in the Internet Archive, in a section titled ‘Nambi Narayanan Papers.’ (One feature in this, the sixth in the series, shows how a scribe of this paper systematically, mercilessly, strips Nambi Narayanan of all his pride, prestige and privileged position as a scientist and as a man, by making wild, pedestrian, sub-standard allegations against him. That one piece would definitely make sad reading for any conscientious person).

None of these reports find a place in the newspaper clippings given at the back of the book ‘Chaaram’ or in the site that can be accessed through a QR code provided by it.

Perhaps it was felt that display of such sleazy features would only substantiate the charge that the newspaper was not at all urbane in its handling of this great, great non-case.

02-Aug-2025

More by : P. Ravindran Nayar