Feb 07, 2026

Feb 07, 2026

Arundhati Roy on her mother Mary Roy

“I left my mother not because I didn’t love her,

but in order to be able to continue to love her.

Staying would have made that impossible.”

It is through such a paradoxical statement, a conundrum, that Arundhati Roy sums up the early phase of her difficult relationship with her mother in her newly published memoirs, titled ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me.’

It is through such a paradoxical statement, a conundrum, that Arundhati Roy sums up the early phase of her difficult relationship with her mother in her newly published memoirs, titled ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me.’

When Arundhati just turned 18, a bright-eyed new adult, she chose to unshackle herself from her unenviable domestic environs and run away to distant New Delhi. And, for the next several years there was apparently no communication between the mother, Mary Roy, and the daughter. Mary Roy never asked her why she left, what she did during that long interval and what she achieved. No questions at all.

That was Mary Roy, a no-nonsense individual and an indefatigable fighter in her own way, who carved a niche for herself in Kerala’s social history as an educator and as the person who legally wrested for Christian women equal rights over family properties, something that had been denied to them from time immemorial.

In spite of what can be described as a love-hate relationship, Arundhati was “heart-smashed” when her mother passed away in September 2022. Her anguished response came as a great surprise to her elder brother. “I don’t understand your reaction. She treated nobody as badly as she treated you.”

But Arundhati says she has put all that behind her a long time ago. “I can understand him feeling that I was humiliating myself by not acknowledging what has happened to us as children.”

In ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me,’ she gives a disturbingly graphic account of that difficult childhood, giving vignettes of an alcoholic father who got separated from her mother, a mother who was at times ‘uncontrollably irrational’ and who had no qualms in beating a child, a child who found herself to be homeless in Assam, a squatter in Ooty and an unwelcome guest in her ancestral family house at Ayemenem, Kottayam.

Several years after she went away to New Delhi, to complete her graduate course in Architecture, do some designing jobs, involve in film making and shine as a writer, there was a “brittle, tentative reunion” following which Arundhati regularly visited her mother over the years “as a woman watching another with love and admiration.”

“In that conservative, stifling little south Indian town, where in those days women were only allowed the option of cloying virtue, my mother conducted herself with the edginess of a gangster,” she says.

“I watch her unleash all of herself – her genius, her eccentricity, her radical kindness, her militant courage, her ruthlessness, her generosity, her cruelty, her bullying, her head for business and her wild unpredictable temper……. It was nothing short of a miracle – a terror and a wonder to behold.”

This description fitted Mary Roy very well indeed. She had the moral courage to abandon her husband when she realized that he was an incorrigible alcoholic, and with nothing in hand to fend for herself and her children, she decided to return to Kerala from a remote Assam tea estate where her husband worked as an assistant manager.

The first port of call she touched on the way back was Ooty, where her deceased father had a partially unoccupied building. She stayed there for some years against the wishes of her brother who made a futile attempt to evict her, an action that sowed the seeds for the later legal battle that ultimately led to the Supreme Court setting aside Christian inheritance laws and according equal rights to Christian women to family property.

When her asthmatic health condition did not permit her to continue in Ooty, Mary Roy and her children further moved down to her ancestral home at Ayemenem in Kottayam, again as unwelcome guests.

Gradually, she paved the way for her future role as an educator by starting a small school for seven kids in a room rented from the Rotary Club. It was this school that in later years grew banyan like to one of the most reputed secondary schools in the state, eponymously named ‘Pallikkoodam.’

Arundhati poignantly brings home the pain and pathos of her childhood days by using a domestic help, Kurussammal, as a foil to show what all she missed from her mother. “It was Kurussammal who taught us what love was. What dependability was. What being hugged was.”

And the image cut out by Arundhati for herself in Ayemenem appeared to be that of a rebel, a rebel against everything, her mother, her father, her unwholesome but rich family. She was more at home outside her home, in the wilds, or on the banks of the river at Ayemenem and the adjective she uses to describe herself is ‘wild.’

No wonder then that some of that wild or rebellious streak of her young days remained with her in later life even as her innate talents flourished and fulminated to make her one of the most illustrious wordsmiths of modern times.

Reading her account of that flawed childhood a reader could only empathise with her, not finding fault with her for some of the controversial positions she took in later life, but perhaps blaming the adverse circumstances that shaped her character, her psyche, her outlook on life.

I for one had once idolized Arundhati Roy after reading her fantastically lyrical debut novel ‘The God of Small Things,’ but later disliked her to a great extent for what I considered to be the wrong kind of activism she seemed to relish in, an activism that appeared to pit her against the very idea of India. For me, many of her accusations were unfounded and many of her assertions outlandish or outrageous.

In ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ she specifically mentions this and tries to put the record straight. “The more I was hounded as an antinational, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged.”

In her intense, lyrical narrative, which incidentally is reminiscent of her debut novel, she explains how a thaw came about in her relations with her mother. As years passed by, it was possible for Arundhati to look at her mother in a different, respectful, meaningful way.

Who knows, a time may come when she has a different perspective altogether on India, different from the shrill activist voice and militant stance on many a social or political issue for which she is famous.

Then, perhaps, Mother India will come to her the way Mother Mary has come.

A review of the book will not be complete without a reference to its title and its cover. ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ is taken from a Beatles song, ‘Let it be,’ written by Paul Macartney and John Lennon. The song is a tribute to Paul’s deceased mother Mary Macartney. The lyrics go like this:

When I find myself in times of trouble,

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, ‘Let it be’

And in my hour of darkness

She is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, ‘Let it be’

In her dedication of the book to her mother, Arundhati Roy has brought out the difference between the two Marys: ‘For Mary Roy, Who never said Let It Be.

Also, the Mary described by Macartney is a world apart from the Mary described by Arundhati. The former is a soothing, consoling presence, while the latter projected by Arundhati is as irascible as can be. Did Arundhati choose this title to bring out the contrast between the two Marys, the same way she used a domestic help as a foil to her mother?

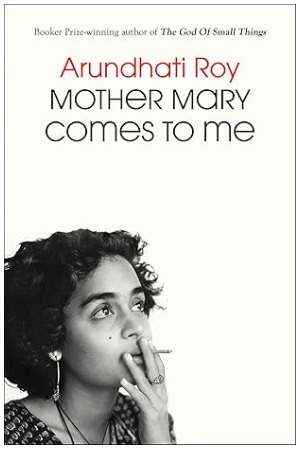

The book published by Hamish Hamilton in the UK has a line drawing of the author for its cover. The Indian edition brought out by Penguin- Random House has a photo of a teenaged Arundhati Roy indolently smoking a beedi. The cover indeed has a reference to her initial years in New Delhi.

On her first visit to New Delhi, a diffident, fearful Arundhati, thoughtfully carrying a knife in her bag, asks an autorickshaw driver whether he knows where her aunt resides. “He took a deep drag of his beedi and turned away, looking bored. Two years later I was the one smoking beedis and cultivating that peerless look of bored disdain. In time I traded in my knife for a good supply of hashish and some big-city attitude. I had emigrated.”

How appropriate then is the cover, even considering the disclaimer by Penguin that the picture is for representational purposes only? Smoking and drug use, whether in the past, present or future, are bad. Won’t the picture of a defiant, teenaged Arundhati smoking beedi be taken as a celebrity endorsement of a very bad habit?

06-Sep-2025

More by : P. Ravindran Nayar