Feb 08, 2026

Feb 08, 2026

Origins, Religious Transformation, and the Shift in Temple Administration

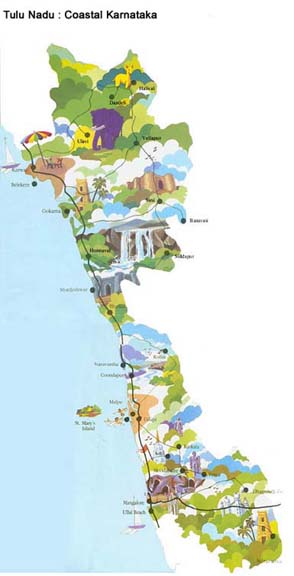

The Tulunadu region of coastal Karnataka is home to one of the most ancient Brahmin communities of South India—the Sthanika Brahmins. The term Sthanika itself is derived from the Sanskrit word Sthana (place, post, or temple) and literally means the “administrator or person in charge of a place.” This term appears frequently in historical records, confirming that Sthanika Brahmins historically held positions of authority in both temple administration (Dharmadhikaris) and local governance.

The Tulunadu region of coastal Karnataka is home to one of the most ancient Brahmin communities of South India—the Sthanika Brahmins. The term Sthanika itself is derived from the Sanskrit word Sthana (place, post, or temple) and literally means the “administrator or person in charge of a place.” This term appears frequently in historical records, confirming that Sthanika Brahmins historically held positions of authority in both temple administration (Dharmadhikaris) and local governance.

This detailed essay provides a historical analysis of the Sthanika Brahmins, focusing on their original role as native priestly administrators, the internal emergence of the Shivalli Brahmin community, the powerful impact of Madhvacharya’s Dvaita Vedanta movement, and the ultimate decline of their temple management rights due to legal frameworks introduced during the British colonial period.

Epigraphical Evidence and Early Role

Numerous stone inscriptions and copper plate records confirm the Sthanika Brahmins’ established role as temple managers and priests in Tulunadu for centuries, sometimes predating the 10th century CE. Their functions were unique, combining both religious and secular duties.

The Mallayyanahalli Inscription (CE 1288)

This inscription explicitly names “120 Sthanikas” involved in significant donations and management decisions related to the Goreshvara Devaru temple, proving their institutional presence as a community of administrators. (Source: History of Kukke Subrahmanya Temple, Scribd, 2024 edition)

Administrative Authority

Records from Udupi, Barkur, and Koteswara refer to Sthanikas as sthana-adhikaris or tantragamis (chief ritualistic authorities). This signifies that they were not merely ritual specialists but also custodians of vast temple lands, managers of revenue, and, in some cases, local judicial authorities (Dharma-niraya) within the sthana or temple jurisdiction. (Source: Subramanya Sabha Archives, Udupi District)

This evidence clearly shows that the Sthanika Brahmins formed the crucial administrative and priestly layer of temple culture in Tulunadu before the significant medieval religious shifts.

Emergence of the Shivalli Brahmins and the Dvaita Influence

The spiritual landscape of Tulunadu underwent a profound transformation with the rise of Sri Madhvacharya (1238–1317 CE) in Udupi, the founder of the Dvaita (dualistic) school of Vedanta.

Religious Schism

Madhvacharya’s philosophy, emphasizing the supremacy of Lord Vishnu (Vaishnavism), attracted many Sthanika Brahmins who were traditionally followers of Smarta traditions (Advaita, worshipping Shiva, Shakti, Vishnu, Surya, and Ganesha equally) and whose primary deity was often Lord Subrahmanya.

The Shivalli Branch

Historical accounts suggest that a key section of the original Tulu Brahmin stock, including members of the Sthanika Brahmin community, accepted Madhva’s teachings. This group became the Shivalli Brahmins, the dedicated Vaishnava branch of the region’s native Brahmins.

Institutionalization

The Shivalli Brahmins, guided by Madhvacharya, went on to establish the eight Udupi Mathas (Ashta Mathas), making Udupi the stronghold of Dvaita philosophy. While embracing Vaishnava philosophy, they retained common cultural elements with Sthanika Brahmins, such as the use of Tulu as their mother tongue (Brahmin Tulu dialect). (Source: ShivalliBrahmins.com, “The Tulu Brahmins: Beginnings and Evolution,” 2023)

Thus, the Shivalli Brahmins emerged through a process of religious specialization and philosophical choice within the existing Tulu Brahmin fold, rather than as an entirely distinct immigrant group.

Socio-familial Dynamics and the Lineage Continuity of the Sthanika Brahmins

Beyond the purely theological transformation that accompanied the rise of Madhvacharya’s Dvaita movement, socio-familial dynamics within traditional Sthanika households likely played a significant role in this internal diversification.

In the hereditary system that governed temple administration, priestly rights, and revenue management, authority was typically vested in the eldest male member of the family or lineage. This practice, rooted in the concept of kuladhik?ra (hereditary office), ensured continuity but also unintentionally restricted opportunities for younger members within the same family.

As a result, the younger brothers and their descendants—often deprived of hereditary access to temple offices or lands—may have sought alternative religious and social pathways. The emergence of Madhvacharya’s Vaishnava movement in the 13th century CE provided precisely such an opening. By embracing the Dvaita school and associating with the organized matha structure, these families could gain renewed identity, institutional backing, and community standing.

Hence, it is plausible that a section of the younger lineages from the broader Sthanika fold aligned with Madhva’s Vaishnavism, forming the early nucleus of the Shivalli Brahmin community.

Conversely, the present-day Sthanika Brahmins are regarded as the continuators of the elder hereditary lineages—those who preserved the original Smarta–Shaiva–Shakta traditions and maintained the ancestral administrative and priestly offices in the ancient temples of Tulunadu. This continuity highlights how Tulunadu’s Brahmin society evolved through internal diversification while sustaining a shared ethnic and cultural foundation.

Continuity and Coexistence of Dual Traditions

Despite the rise of the Vaishnava-focused Shivalli Mathas, the Shaiva-Shakta Smarta worship continued strong among Sthanika Brahmins. This led to a unique religious symbiosis in Tulunadu.

Smarta Centers

Major pilgrimage centres dedicated to Shiva and the Goddess, such as Kukke Subrahmanya, Kateel Durgaparameshwari, and Kollur Mookambika, retained Sthanika priests and hereditary management for centuries. Their allegiance remained with the Advaita tradition, primarily following the Sringeri Sharada Peetham. (Source: Sthanika Brahmin community archives and traditions)

Symbiosis

This division meant that the Sthanika community continued to maintain the older temple structures and deities of Tulunadu, while the Shivalli community focused on propagating the newer, organized Vaishnava Dvaita tradition. Both groups, though distinct in their sampradaya, shared geographical and social roots.

The Disruptive Impact of British Colonial Legislation

The arrival of the British administration fundamentally altered the traditional, autonomous governance of temples and religious endowments. The colonial government’s goal was primarily revenue extraction and the replacement of local authority with bureaucratic control.

Key Legislation

The Madras Regulation VII of 1817 and the subsequent Religious Endowments Act of 1863 centralized control. These laws brought all major temple revenues and properties under the supervision of the colonial Board of Revenue.

Undermining Hereditary Rights

The Acts gave the Board power to appoint trustees or agents, often overriding hereditary or community-based rights that the Sthanikas had held for centuries. This shift targeted local power structures like the Sthanikas, who often resisted colonial land and revenue policies. (Source: Madras Presidency Archives; Organiser.org, “Trojan for Trampling Temples,” 2018)

Consequence

The British intervention dismantled the Sthanikas’ ancient role as hereditary trustees and local administrators, replacing it with a system of government-appointed supervision, thereby leading to a significant loss of status and control over institutions.

Gradual Transfer of Temple Management

The loss of hereditary control under British law was compounded by other social and political factors, leading to a gradual transfer of temple administration in several areas.

Matha Organization

The highly organized Madhva Mathas (Shivalli institutions) proved more adaptable to the new centralized administrative systems imposed by the British compared to the decentralized Sthanika-managed temples.

Patronage and Stability

The institutional strength of the Mathas, often backed by royal and local patronage, allowed them to step into managerial roles, particularly where the political stability of the local dynasties (who supported the Sthanikas) had weakened.

The Outcome

Consequently, many temples in areas like Udupi transitioned to Shivalli Vaishnava management. However, the largest Shaiva and Shakta centres, due to strong local resistance and enduring traditions, retained Sthanika priests, illustrating the complexity of the colonial-era power dynamics.

Conclusion

The Sthanika Brahmins of Tulunadu stand as a testament to the longevity and adaptability of Brahminical society in South India. Their identity as the original hereditary administrators and priests of the region is well-documented by historical inscriptions. The evolution that gave rise to the Shivalli Brahmins showcases the dynamic nature of Hinduism, embracing major philosophical changes while retaining regional roots.

Crucially, the intervention of British colonial temple laws fundamentally restructured the region’s religious governance, replacing centuries of Sthanika autonomy and hereditary management with external bureaucracy. This power shift was a primary driver in the eventual transition of temple control, though both Sthanika and Shivalli Brahmins remain integral—each preserving a vital stream of Hindu dharma: the former safeguarding the ancient Shaiva–Shakta Smarta lineage, and the latter embodying the Vaishnava Dvaita tradition.

References

— “History of Kukke Subrahmanya Temple,” Scribd, 2024.

— Subramanya Sabha Archives, Udupi District (official website).

— “The Tulu Brahmins: Beginnings and Evolution,” ShivalliBrahmins.com, 2023.

— “Trojan for Trampling Temples,” Organiser.org, April 26, 2018.

— Madras Regulation VII of 1817 and Religious Endowments Act of 1863, British India.

— South Canara District Gazetteer, 1894.

— Epigraphia Carnatica, Volumes II–V, Karnataka State Archives.

— Wikipedia – Sthanika Brahmin

— Tamil Brahmins Historical Blog, “Temples and the State in India,” 2015.

08-Nov-2025

More by : Prof. Kiran Shanbhag