Feb 25, 2026

Feb 25, 2026

"My mother was 12 years old when she joined 'nautanki'," says Madhu, herself a renowned nautanki artiste, and the daughter of the famous Gulab Bai. "She was fascinated when she saw a nautanki at a mela (fair). She had a natural flair for singing," Madhu says of her mother.

"My mother was 12 years old when she joined 'nautanki'," says Madhu, herself a renowned nautanki artiste, and the daughter of the famous Gulab Bai. "She was fascinated when she saw a nautanki at a mela (fair). She had a natural flair for singing," Madhu says of her mother.

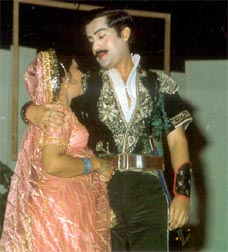

Nautanki or song-dance-drama, was in the secular folk theatre tradition. And it was once a major form of entertainment, communication and education for the masses throughout northern India. Up until the mid-1930s, men performed all the roles in a nautanki.

Gulab Bai however, was the first female nautanki artiste. Within a couple of years, she was playing the heroine - roles that are the stuff of dream and legend - Laila in 'Laila Majnu', Taramati in 'Raja Harishchandra', Shireen in 'Shireen Farhad', Farida in 'Bahadur Ladki' and so on. She honed her innate talent through disciplined practice. By the late 1930s, she had reached the heights of fame and popularity.

Gulab Bai died in 1996; but her influence lingers still. And while she lived and performed, she received several awards - a Padma Shree, the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Sangeet Natak Akademi award, and the Yash Bharati. No mean achievements, these, for a woman born into a landless, low-caste family. The eldest of 10 siblings, Gulab would recall during her last years, "When we were small, my mother spread out one lehenga (long skirt) to cover all of us as we slept. We slept on straw in the winter, in a tiny hut".

By the 1940s, Gulab Bai's salary was Rs 2,200 per month - a huge sum in those days. She supported her parents and younger siblings, and built a magnificent haveli (mansion) in Balpurva, her home village in Farrukhabad district of UP. She also renovated the Phoolmati Devi temple where she had worshipped since childhood. The first nautanki show of every season was performed at the temple. Gulab Bai's sisters Chahetan, Paati Kali and Sukhbadan followed her to the stage.

In the mid-1950s, Gulab Bai set up her own company - the Gulab Theatrical Company. Recalls 60-year-old Binda Prasad Nigam, who joined the company as an actor in the early '60s, "Gulab Bai was totally immersed in the world of song, dance and story. She was a great performer, and a superb manager. She stood in the wings and looked over each artiste - makeup, costumes, etc. She was equally concerned about the words, punctuation, music and dialogue. She made sure every detail was correct."

Crowds of men, women and children flocked for nautanki performances, which were held in the open, or in a large tent, on a makeshift stage. Artistes sang full-throated, their voices carrying across a crowd of two or three thousand people. Audiences sat spellbound. Performances began at 10 or 11

at night, and continued up to 4 or 5 am.

Women on stage were an anomaly in north-India's patriarchal, purdah-bound society. Says Munni Bai, Gulab Bai's niece, "We always had men falling for us, boys would follow us. We women stayed in the tents in the daytime; we slept till late morning. We were Hindus, Muslims, all together."

Troupes of 60 to 70 people - artistes, musicians, technicians, carpenters, tailors, and cooks - would travel together, and set up camp at the site of the fairs. A mela would sometimes go on for a month. The company would perform a different nautanki every night.

Ramprasad Verma played the harmonium in Gulab Bai's company, and was its music director for over three decades. "Bai understood what art is. She was concerned about each artiste, and took care of entire families. Everybody loved her."

Adds Saajan, who acted in her Company - "After her death, we feel we have no protector." His aged mother, Hiramani, nods agreement. Hiramani came from Benaras to work in Gulab Bai's company. Other artistes came from Aligarh, Mathura, Banda, Agra, Mahoba and several other towns and villages.

By the '60s, Gulab Bai had retired from playing the role of a heroine. Sukhbadan, her youngest sister, filled the vacuum. And soon Asha Rani, Gulab Bai's elder daughter, also began to perform. Both Sukhbadan and Asha were talented, and became popular.

Meanwhile, Gulab Bai continued singing to packed halls. Her most famous 'dadra' was the rage for decades throughout north India - 'Nadi naare na jao Shyam, paiyan padoon'. The song was among several recorded by HMV in the '50s and '60s. Film producers approached Gulab Bai more than once. But she refused to look towards cinema - "If we go off to Bombay, what will happen to nautanki?" she would say.

During her last years Gulab Bai was sorely concerned about the decline of nautanki. Partly due to the impact of cinema and television, nautanki began to change for the worse. "We performed roles. We went on the stage fully robed, wearing elaborate costumes. Today, the tradition survives only in

some areas. In most places the audience watches a drama for a while, then the young men start shouting for dancing girls. These girls cannot sing or act. Earlier we were treated with enormous respect, as artistes," rues 55-year-old Kamlesh, a nautanki heroine in her youth.

Older nautanki artistes now live in abject poverty - packed into tiny rooms in tumbledown colonies such as Kanpur's Bakarganj and Rail Bazaar. Gulab Bai had lobbied with the government to set up a housing colony for nautanki artistes, and pensions for the aged impoverished artistes. As a result, the Sangeet Natak Akademi has been doling out a pension of Rs 1,000 per month (1US$=Rs47) to a few older artistes.

Madhu and Asha, who continue to run the Gulab Theatrical Company, say more thought has to go into supporting nautanki. Older artistes could well teach the intricacies of the art to others, but their art is dying with them. Explains Madhu, "Many artistes' daughters have taken up commercial dancing - at weddings, functions, and hotels. Girls who grow up in nautanki families are good dancers. What option do they have? These girls run the risk of becoming sexual commodities, which was not the case earlier."

Madhu herself is an exception - her mother Gulab Bai had sent her to school. She excelled in studies, and wanted to become a doctor. But when she joined college, Gulab Bai was unwell, and there was a financial crisis. Madhu pitched in by giving a few performances. Finally, she gave up her

studies. In her early 40s now, she says, "We get only a few contracts a year. We cannot keep permanent staff. Most melas only want dancing-girls. Even if there is demand for a nautanki, it is performed in one hour. The payment is very low. Most artistes are unemployed most of the time."

Clearly, it is time for the government and art agencies to provide sensitive support to nautanki artistes, to enable the survival of this grand, operatic form of theatre.

20-Jul-2003

More by : Deepti Priya Mehrotra