Feb 22, 2026

Feb 22, 2026

I do not know who I am.

Let me be precise, clearer: I know what people call me to my face, sometimes I even know what they think of me. But this is all reflected knowing-ness, a construction of myself as a mosaic. So lets put it this way - I am everything that everything else isnot. I am not my mother, not my father, neither my aunt nor my uncle. I am not this pen on the wooden desk in front of me, nor the tilted lamp that hangs above. I am not this rotting plastic diskette slotted into a drawer, nor this pile of paper on the right. I am not this curtain, and neither am I the wet monsoon shower that comes down slowly outside this window. I am not the mosquitoes caught in the netting at night, nor the maid that sweeps out the room. I am none of these things, nor anything that has ever been anything that I can name.

If I cannot say what I am, let me first, at the very least, find a measure of comfort in knowing what I am not. In the way logic works this is an important first step, eliminating the poisoned bottles, as it were, and coming down to a final, fatal choice.

And when I think about it, it seems simple to know why I am not any of these things. I can move my hands and feet upon command. I can wriggle my fingers, I can raise my eyebrows, I can stop my breath (for a while, at least), and I can wipe tears from my face, or another's. So then this 'myself' comes down to being those things I have a measure of control over. But what, then, is their name? There are labels for all of these things, but none of them is me.

Lets not digress, lets come back to definitions, lines and facts. Its simple to think of the world as divided into nations, but right now I'm not sure if that is a luxury that I can afford. In the land of my birth, people ask me if I am a foreigner and deny what is to me an essential part of myself. I have always thought of myself as Indian, schooled in these things by education and society. Yet this concept is difficult to hold on to, is constantly under attack by the very people with whom I profess similar citizenship. I asked a man in Jaipur once - he was trying to sell me kurtas - what it was about me that he took to be 'foreign'. 'Your clothes, your hair, the air that you have - he replied. And yet I doubt that the answer is as simple as that. Perhaps you breathe and live in another land, and you become, in some ways, part of it, something that goes inside you and is not easily removed. I am sure I am not alone, but just a very small part of a global community of people who feel the same - foreigners in their own land, and foreigners outside. This is an uncomfortable feeling in the beginning, for I feel the need to belong; to be part ofsomething, and do not like my patriotism or loyalty being tested. I did what I did not because of choice, or free will, or an expectation of reward, but because this is the way my life turned out and because there was something that needed to be answered, a need to see what was beyond the horizon.

To be fair, this process works in reverse as well. If I am seen as different, then I too look out with different eyes. This trip across India is a (re) discovery, of the land, of its people, but also of myself. I went outside this land to find myself, to answer a call of what-I-know-not, and I find that the process is not over. There are new layers to this land, waiting to be uncovered, and as I uncover each I find a little of myself revealed - like a reflection in a hall of mirrors that repeats infinitely; or a fractal pattern in a kaleidoscope that twirls around to catch its own tail. But if a point of origin has to be taken, then let it be here, right now, from where I grew up, in a town that came out of the dust, a creation of modern India, a 'foreign' implant that, in a fantastic reversal, is now becoming 'Indian', in all the problematic senses of that word.

So then let us start, and choose a beginning. Let's zoom into Chandigarh from the air. The mighty Himalayas border and defend India, and give rise to five great rivers and a land named after them, the Punjab. And then in 1947 an Englishman draws a line in the sand and cuts off one from the other. A few years later a Frenchman draws still more lines - a grid laid out on a plain at the foot of the mountains, he calls this a town, a new capital town for a new country. But this is 60 years ago, and a different story. We are here today, in the center of this town, where there is a clunky structure in concrete and stone. Zoom in a little more and we'll see people, thousands of them, and buses, hundreds of them, and now we know this is a bus terminal. An incongruous beginning, but at least is a point in time and space. Oh wait! - we know the space, but lets also set a time - and so its morning, the 24th of June, and lets add a little color and describe how it feels.

Of all the seasons there are in north India needs to be added another one - that of the time spent waiting for the monsoon. While one can write lyrical stories of Indian summer and the beauty and fury of the rains, very little can actually describe being in this time - when to the full heat of summer is added the tension and humidity in the air. Its exactly this time that I chose for a trip, of all places, to Rajasthan - that land of kings and forts. Getting there, however, is not so easy from Chandigarh - a young city though curiously old, that epitomizes the best of new India, and in some ways, its worst.

The bus from Chandigarh to Delhi takes 5 hours and costs between 100 and 300 rupees. This depends on the kind of bus, the 'deluxe' stopping rarely, its interiors padded with fake leather, and a television hanging in the front providing movie entertainment. Public road transport remains the almost exclusive preserve of state governments, and in this case Haryana Roadways paints its deluxe buses an inevitable blue and grey reflecting the monsoon sky, scurrying and swarming over the state like ants to a feast. Monsters on the road, these buses are the lifeline of India, accessible to all for a price lesser than, for most things, the cost of a beer. The fleet was new some years back, now the buses are beginning to reflect the toll of years of use and misuse, and heavy service. In the de-luxe version and the anonymity that marks public transport there are, if nothing else, two events of social significance - the first when the ticket assistant hands out bottled water; and the second when the bus stops for its passengers to have a meal. Suffice it to say that 'deluxe' and bottled water go together. A potentially potent status symbol, bottled water is right up there with the other icons of new India - the mobile phone and the Hyundai - and goes well with the 'deluxe' of the bus, and the price of the ticket.

The bus from Chandigarh to Delhi takes 5 hours and costs between 100 and 300 rupees. This depends on the kind of bus, the 'deluxe' stopping rarely, its interiors padded with fake leather, and a television hanging in the front providing movie entertainment. Public road transport remains the almost exclusive preserve of state governments, and in this case Haryana Roadways paints its deluxe buses an inevitable blue and grey reflecting the monsoon sky, scurrying and swarming over the state like ants to a feast. Monsters on the road, these buses are the lifeline of India, accessible to all for a price lesser than, for most things, the cost of a beer. The fleet was new some years back, now the buses are beginning to reflect the toll of years of use and misuse, and heavy service. In the de-luxe version and the anonymity that marks public transport there are, if nothing else, two events of social significance - the first when the ticket assistant hands out bottled water; and the second when the bus stops for its passengers to have a meal. Suffice it to say that 'deluxe' and bottled water go together. A potentially potent status symbol, bottled water is right up there with the other icons of new India - the mobile phone and the Hyundai - and goes well with the 'deluxe' of the bus, and the price of the ticket.

Its morning at 8 am on the 25th of June, and the day is already hot, and getting hotter. The monsoon hangs in the air without quite being there, an omnipresent mugginess. The bus rumbles its way out of its Chandigarh bus terminal. In 15 minutes we cross the city limits. The road link to Delhi crosses Ambala, the largest military base in north India, where MiGs regularly blast across the sky and trains can be seen loading and unloading lumbering T 72 tanks. This is also historic country, the heart of north India, with Kurukshetra of Mahabharata fame, Shahabad where the river is named after the sage Markandeya, and the battle plains of Panipat, where the fortunes of Delhi were made and unmade more than once. There is history spilling out of the seams, and there is a place for it, but for the moment there is the present. The road is busy, full of traffic now near the middle of the day, and this is India of truckers and new construction projects, of highway towns and content fields smiling upwards, waiting for the next rains. It's fascinating to watch a road link develop. The Delhi-Chandigarh road corridor is one of the busiest in India, and an offshoot from one of India's oldest, the so-called G.T. road. The Grand Trunk Road was constructed by Sher Shah Suri, the Afghan ruler of Delhi who temporarily supplanted the fledgling Mughal dynasty in the 16th century. A prolific builder, he connected the breadth of his empire, from the Punjab to Bengal to cement his rule. Ever since, the G.T. road is the main artery of north India and the vast Gangetic plain. Today the modern road roughly parallels the original, and kos minars from the 16th century and later still mark off distances. Crumbling, in disrepair, they've survived several empires and are witnessing the rise of yet another - the new Indian State.

The Grand Trunk Road is one of the chief sites of the country's efforts to build a world-class road network. Widened to two, and then four lanes, construction continues, with international construction firms joining in the act, bidding for contracts that guarantee work for decades. None of this new road infrastructure comes free - a price has to be paid. The Indian janta, long used to free government sops, is getting used to the idea of paying toll for a road. Perhaps this is not so alien as it sounds, in the time of the Mughals caravans and traders had to pay tax for safe passage and the protection of empire, and what was the British empire but a wholesale toll tax on an entire nation?

The Grand Trunk Road is one of the chief sites of the country's efforts to build a world-class road network. Widened to two, and then four lanes, construction continues, with international construction firms joining in the act, bidding for contracts that guarantee work for decades. None of this new road infrastructure comes free - a price has to be paid. The Indian janta, long used to free government sops, is getting used to the idea of paying toll for a road. Perhaps this is not so alien as it sounds, in the time of the Mughals caravans and traders had to pay tax for safe passage and the protection of empire, and what was the British empire but a wholesale toll tax on an entire nation?

Recognizing the importance of this corridor, the 120 mile/250 kilometer route to Delhi from Chandigarh is now almost a continuous urban ribbon that conceals and complements the agricultural hinterland within. Le Corbusier mooted the idea, in Les Trois Etablissements Humains, of something that looks almost similar ' linear urban development leading to urban centers, and farming lands within the interstitial spaces. There is growing wealth here, and the juxtaposition of the very rich with the very poor, a frisson of society rubbing against each other, mixed with the heat of the plains and the green fertility of the land, villages, luxury pleasure resorts and the inevitable shrines where truckers and the affluent alike stop. India as one gigantic city? ' this is probably unlikely in the near future, but there are times when the thought does not seem impossible. There is energy mixed with vapidity in the air, a miasma of the past mixed with hope and belief in the future that rises like elusive mist from a hot road.

The bus is full today with people short-tempered from the heat and the rattling buzz from overhead speakers. The woman sitting next to me is thin; tired-looking, with a determined face. We make no conversation but share the newspaper; some time down she sleeps ' the sun on her face and her bag on her lap. Some people have the gift of conversing with total strangers ' to make a friend in minutes and share their lives in the anonymity of a public space, in the perfect knowledge that they will never see this person again. The perfect conversation, the best opening line, usually comes to me about one hour too late.

But there is little time to think of this for too long. A short five hours later, there is Delhi. It can be smelt and felt long before it is. At the entrance to the city; a huge government land reclamation/waste disposal project has been on for more than a decade, creating mountains of filth that gives off toxic odors. It is staggering in its sheer scale. We read of statistics about human waste, but this is not a statistic, not a number, it is reality in your face. The colossal mountain of human and industrial waste adorns the entrance to Delhi, a monument to the city and the amazing organizational powers that is a national government. To be fair, this is temporary - another such project along the banks of the Yamuna in Delhi has now been converted into a public park. This too will end sometime, but for the moment the stench is amazing, but it is also an unforgettable memory of Delhi, mingling with everything else.

The rest, of course, is hot, humid, and huge.

Where the lanes of the old town intertwine impossibly into one another, the fort and the huge mosque are the centers of activity; giving slowly out to Lutyen's plan, two cities separated by time and belief, both testimonies to empires that have now gone. They are replaced by a new empire in the making, one that may outlast the ones before. The Delhi Metro is cutting huge ruthless scars across the city, contemptuously stopping traffic and creating a whole new hierarchy of spaces, making the city unrecognizable in the short space of three years. Was this what Haussmann's Paris was like? The difference is that Haussmann is History and this is here, right now; a community of millions whose sense of social space will be changed drastically ' is changing drastically ' for the foreseeable future. Urban History is being created, and one can only pass through and carry a few impressions that will linger.

The metro itself, where it runs, is clean and fast. These are desirable qualities in a city long accustomed to slow buses and overcharging taxis. Multinational construction or not, Delhi Metro's architectural aesthetic is one that can best be described as 'Indian Public Transport Terminal chic', a lasting quality that emerges in bus terminals, airports, railway stations, and now the Delhi Metro. Some of its characteristic features are grey stone finishes on the walls and floor, creeping potted money plants serving as corridor and public space punctuator, aluminum-framed window and door openings, and the ubiquitous wooden security gate that prefaces entrances. The fact that it is often unmanned does not detract from its omnipresence. Having said all this, there is something else, a quality that does not communicate well in words, perhaps a way in which public buildings are built, perhaps it is Delhi itself, that gives to even a new building a sheen of age, like it has always been there, equally legitimate in history right along the Red Fort and the Jumma Mosque. The stones of Delhi breathe and give off their own odor tainted by centuries, and at night the lanes in the Jumma Masjid throb with activity, contemptuous scoffers at the others, the Delhi of the hoi-polloi and art festivals. Art and Culture are the bywords of those who can afford to buy authenticity and make it into a spectacle.

The metro itself, where it runs, is clean and fast. These are desirable qualities in a city long accustomed to slow buses and overcharging taxis. Multinational construction or not, Delhi Metro's architectural aesthetic is one that can best be described as 'Indian Public Transport Terminal chic', a lasting quality that emerges in bus terminals, airports, railway stations, and now the Delhi Metro. Some of its characteristic features are grey stone finishes on the walls and floor, creeping potted money plants serving as corridor and public space punctuator, aluminum-framed window and door openings, and the ubiquitous wooden security gate that prefaces entrances. The fact that it is often unmanned does not detract from its omnipresence. Having said all this, there is something else, a quality that does not communicate well in words, perhaps a way in which public buildings are built, perhaps it is Delhi itself, that gives to even a new building a sheen of age, like it has always been there, equally legitimate in history right along the Red Fort and the Jumma Mosque. The stones of Delhi breathe and give off their own odor tainted by centuries, and at night the lanes in the Jumma Masjid throb with activity, contemptuous scoffers at the others, the Delhi of the hoi-polloi and art festivals. Art and Culture are the bywords of those who can afford to buy authenticity and make it into a spectacle.

But once again, lets keep the thread. For the moment, the staff at the Metro is friendly and efficient, the trains run fast and on time, and I emerge in Connaught Place, or as a (slightly hysterical) Union minister in the Indian government named it once ' Rajiv Chowk. The allegory of a son resting eternally in his mother's arms (the outer circle of Connaught Place was similarly named Indira Chowk) compares unfavorably and ridiculously to Michelangelo's Pieta.

But once again, lets keep the thread. For the moment, the staff at the Metro is friendly and efficient, the trains run fast and on time, and I emerge in Connaught Place, or as a (slightly hysterical) Union minister in the Indian government named it once ' Rajiv Chowk. The allegory of a son resting eternally in his mother's arms (the outer circle of Connaught Place was similarly named Indira Chowk) compares unfavorably and ridiculously to Michelangelo's Pieta.

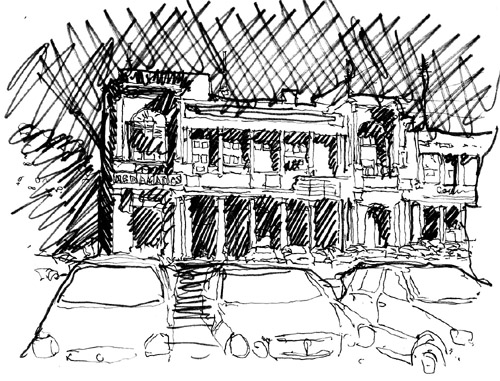

For the moment, Connaught Place remains a familiar, comfortable name for most, and the white-plastered arcades with their Doric colonnades are still the hub and axis around which the two Delhis meet. Much has changed in the last decade, and much is still the same. There are still excellent bookshops, STC's Bankura Restaurant, the Volga where the paparazzi hang out over a beer, the chicken and cheese sandwiches at Janpath, and still Orijit Sen's alternative culture shop the People Tree.

For the moment, Connaught Place remains a familiar, comfortable name for most, and the white-plastered arcades with their Doric colonnades are still the hub and axis around which the two Delhis meet. Much has changed in the last decade, and much is still the same. There are still excellent bookshops, STC's Bankura Restaurant, the Volga where the paparazzi hang out over a beer, the chicken and cheese sandwiches at Janpath, and still Orijit Sen's alternative culture shop the People Tree.

Megha is to meet me at Nizamuddin Station at 2 30 pm, our train to Kota is at 3. There was no real need to stop by Connaught Place, except for the almost inevitability of a visit when passing by Delhi, and to try out the metro. CP is exhausting after a while, its lack of true public spaces for leisure ' and the heat ' meaning that one has to be on the move. What about a redevelopment plan for CP that will connect the roof spaces of the arcades to each other, a public garden that will overlook the Circle, be in it and yet above, connect and still be aloof. This will provide extra real estate that can pay for itself by selling concession spaces, and create that much-needed public green. There are precedents ' examples that have worked well ' the promenade plant'e at Paris for example ' and created new and innovative real estate solutions out of space that lay vacant and unused.

There is time for a little more catching up. Lutyen's Delhi is full of bungalows, their generous space and proximity to Delhi's power centers making it the address of choice for modern India's who's who. Ministers' houses, offices of political parties, judges and generals, the Gandhi family's mini-fortress along Race Course Road, the embassies along Chanakya Puri ' all jostle for space. They are serviced by an army! ' chaiwallahs, taxis, autorickshaws ' and now more recently, patiently-waiting media vans sniffing around and competing for the latest story. The drive to Rashtrapati Bhavan ' that magnificent monument to the British Raj ' is awesome even in the heat, and heat mirages rise up from Rajpath mirroring the illusion. And yet this is not illusion. There is a very real sense of power in the air ' power and opportunity ' and one understands why Delhi has been fought over for centuries. It seems that with each fight the prize grows greater, the stakes higher.

Further away, there is quiet. At Humayun's tomb, there is no more power, not now, though once long ago was a different story. The immensity of this monument is a testament to the incredible power ' concentrated in one man ' that the Mughals wielded at their height. A World Heritage Site, Humayun's Tomb is now accessible for a fee ' Rs. 10 for Indian citizens, Rs. 250 for aliens. Inside, stonecutters work at restoring and repairing the tomb's pink sandstone facing, and the chowkidar offers to open the stairway to the top ' for a fee. I'm content to walk around as it gets time to leave for Nizamuddin, not so far away.

Nizamuddin Railway station is in the heart of one of the older sections of town. Flanked by Humayun's Tomb (gigantic!) on one side, and the kebab sellers of Nizamuddin's old town on the other, the station's recent development is part of a larger project to decongest Delhi's main railway terminals. I sit at the station restaurant, sipping almond milk, waiting. We've been batch-mates in college, Megha and I, and she now works in Delhi with development firms, advising on environmental and management issues. Its almost 3, and then there is Megha hurrying along the platform a few minutes before its time.

27-Aug-2010

More by : Ashish Nangia

|

I like it |