Feb 08, 2026

Feb 08, 2026

During the latter half of the 17th century another foreign power set its eyes on the fruitful Indian trade. They were the last of the four Europeans to make their mark in India (Portuguese, Dutch and the English had preceded them). A French dreamer and entrepreneur Jean-Baptiste Colbert started the French East India Company (Compagnie des Indes Orientales) in 1664 with an investment of fifteen million livres tournois (about 600,000 British Pounds.) The early steps taken to colonize Madagascar proved futile. But in 1669 a trading post was established in Surat by the Francois Caron with the help a Persian named Marcara. Marcara also helped to broker a deal with the ruler of Golconda and established a French trading post in Masulipatam (called Machlipatnam now) giving them access to Bay of Bengal. Within a decade after the birth of the French compagnie, Francois Martin established its Indian headquarters at Pondicherry, eighty-five miles south of Madras. Francois Martin obtained the land from the Muslim governor of Valikondapuram and transformed the small village into a major center after 1674. Another trading post on the banks of the river Hughli named Chandarnagar in 1690, purchased from the Nawab of Bengal completed the tripod of trading posts on both coasts of India, thus emulating the British.

The French also entered into severe competition with the British for the Indian merchandise. Soon the profits posted by the French company surpassed that of the British East India Company. In 1721 the French seized two strategically important islands, Mauritius and Bourbon, in the Indian Ocean that gave them the advantage of swift action to defend its posts in India, if needed. Mahe on the Malabar Coast was annexed in 1725 and Karikal, to the south of Pondicherry was taken over in 1739.

Pondicherry had a checkered beginning. The British, nervous about the intrusion of the newly arrived French, let the Dutch do the fighting with the French. Pondicherry was taken by the Dutch in 1693 but given back to the French in 1697 as part of theTreaty of Ryswick. Francois Martin once again saw to the prosperity of Pondicherry and when he died in 1706, the population of Pondicherry rivaled that of Madras, at about fifty thousand. In contrast Calcutta only had a population of twenty-two thousand in that year. However, they had to abandon their post in Surat and Masulipatam, as it was becoming more and more difficult to defend them.

By the early 18th century the Dutch had appeared to be tired of their Indian trade. After fighting the Catholic Portuguese on religious basis and then the British on the basis of trade rivalry, the Dutch retreated to their Southeast spice trade in Java and left India after 1759. Now there were only two players left in India, the British and the French, not counting the diminished power of the Portuguese, who confined themselves to Goa and its vicinity.

In 1741 a visionary Joseph Francois Dupleix (1697-1764) was given charge of Pondicherry presidency. He was the son of the director-general of the company and had a vision of building a French Empire in India. So far the foreign nationals in Indian soil seemed to have no other interest but to profit from trade so that their mother countries could prosper. But Dupleix had other ideas.

Nabobism of Dupleix

At the home front in Europe, trouble was brewing between the French and the English. Maria Theresa’s disputed claim to the throne in Austria saw both these countries on the opposite sides of the dispute. The European war between them soon spilled over to South India in the summer of 1746. The British captured some French ships and Dupleix summoned help from Admiral Mahe de la Bourdonnais from Mauritius, who sowed up with a formidable armada of naval fleet to quickly defeat the British along the Coromandal coast. Madras fell to the French on September of 1746. Soon Dupleix would become so powerful that he would be the de facto Nawab and Nizam of the Princely states of South India. He never acknowledged the title in public but played a behind the scene game, while maintaining all controls. This ‘game’ of politicking came to be known as ‘nabobism’. Soon the British would emulate this tactic in their pursuit of a British Empire in India.

At the home front in Europe, trouble was brewing between the French and the English. Maria Theresa’s disputed claim to the throne in Austria saw both these countries on the opposite sides of the dispute. The European war between them soon spilled over to South India in the summer of 1746. The British captured some French ships and Dupleix summoned help from Admiral Mahe de la Bourdonnais from Mauritius, who sowed up with a formidable armada of naval fleet to quickly defeat the British along the Coromandal coast. Madras fell to the French on September of 1746. Soon Dupleix would become so powerful that he would be the de facto Nawab and Nizam of the Princely states of South India. He never acknowledged the title in public but played a behind the scene game, while maintaining all controls. This ‘game’ of politicking came to be known as ‘nabobism’. Soon the British would emulate this tactic in their pursuit of a British Empire in India.

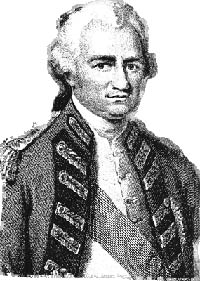

Among the prisoners Dupleix held in Fort St. George in Madras was an English Company ‘writer’ named Robert Clive (1725-1774). The clerk of the British East India Company had attempted suicide out of sheer ‘boredom’ of his hapless job. His life had been spared only because the gun had misfired. Now as a prisoner of the French in Fort St. George, writer Robert Clive analyzed from the motives of Dupleix that all of India was in such political turmoil that it was the right time to attempt imperial conquest and establishment of an empire.

Dupleix played his part as the king maker like the game of chess. There were two principal nawab states in South India, namely Arcot and Hyderabad. Internal rivalry and fratricide had reduced them to bickering kingdoms ready for intrigue and interference. Dupleix got his chance serendipitously. Nawab of Arcot, one Anwar-ud-din, who had been appointed by Nizam of Hyderabad laid claim on Madras and insisted the French hand it over to him in October of 1746. When Dupleix refused Anwar-ud-din attacked Fort St. George with a force of ten thousand men. He was soundly defeated by the smaller French force, a tenth of its size, with the discipline of European fighting squad. Then in 1748 the Nizam of Hyderabad died and this created a vacuum in the most powerful kingdom of the South. He bought freedom for a Chanda Sahib, a son-in-law of the deceased ruler of Arcot, from the Maratha prison by paying a ransom and appointed him as the nawab of Arcot. Dupleix himself refused to be named the nawab three times when proffered the throne. He was content to play the puppetry from behind the screen.

The next chance came when the new Nizam of Hyderabad was assassinated in 1750. Under the command of French lieutenant, Marquis de Bussey, a force marched on Hyderabad and placed Salabat Jang, one of the deceased Nizam’s sons on the throne in Hyderabad. French power in India had reached the zenith as both Hyderabad and Arcot fell under them. The English were scrambling and licking their wounds. But a historic turn of events beyond the control of Dupleix gave the British an opening and thus altered the course of history of India. It came in the wake of a peace treaty between England and France in the continent of Europe.

Reversal of Fortunes - Rise of Robert Clive

The European peace treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle forced Dupleix to return Madras to the English in 1749. Louis the XV and Madame de Pompadour, the rulers in Paris showed little interest in the events in India. With any support from the French rulers in Paris, Dupleix could have been the undisputed de facto emperor on India. Even the Marathas who were very much involved in the South were powerless in the face of brilliant political maneuvering of Dupleix.

British with the second wind they had been afforded by events, learned quickly to play the same game Dupleix had played. Muhammad Ali, who was the son of the deceased Anwar-ud-din, (the erstwhile nawab of Arcot before the French had dethroned him), had fled to Trichinopoly, to the south of the peninsula, where he had fortified his position. The British quickly took his side in his bid to win back the throne in Arcot. Chanda Sahib laid siege on Trichinopoly but waited too long, thus creating a vacuum in Arcot.

Robert Clive, the writer of East India Company now had found his true calling. His failed suicide attempt had given him a new impetus in advancing his position within the Company. Moreover, he found blowing off other’s brains was lot more sporting and to his liking than his blowing his own. Now a captain, Robert Clive volunteered to lead a march more than one thousand miles south in the heat of the summer of 1751 to Arcot. There he found little resistance as the whole garrison was in Trichinopoly laying siege on the fort where Muhammad Ali was trapped. Chanda Sahib had no choice but to end his siege in Trichinopoly and return to Arcot with his army. But “brave” Clive held off for over fifty days with a diminished band of soldiers, and staved off Chanda Sahib. Then with the help of Maratha troops Muhammad Ali triumphed in Trichinopoly and came to the rescue of Clive in Arcot. Chanda Sahib was captured and executed in 1752. Now Clive had become the new “nawab-maker.” The French government did not show any appreciation of the brilliant successes of Dupleix and he was unceremoniously recalled back to France in 1754 for “wasting too much investment on unprofitable ventures.” The last nail on the coffin of any design of French imperialism in India by Dupleix had been hammered by nonchalant French rulers in Paris. Dupleix lived out the rest of his years in disgrace and in oblivion.

Robert Clive, the writer of East India Company now had found his true calling. His failed suicide attempt had given him a new impetus in advancing his position within the Company. Moreover, he found blowing off other’s brains was lot more sporting and to his liking than his blowing his own. Now a captain, Robert Clive volunteered to lead a march more than one thousand miles south in the heat of the summer of 1751 to Arcot. There he found little resistance as the whole garrison was in Trichinopoly laying siege on the fort where Muhammad Ali was trapped. Chanda Sahib had no choice but to end his siege in Trichinopoly and return to Arcot with his army. But “brave” Clive held off for over fifty days with a diminished band of soldiers, and staved off Chanda Sahib. Then with the help of Maratha troops Muhammad Ali triumphed in Trichinopoly and came to the rescue of Clive in Arcot. Chanda Sahib was captured and executed in 1752. Now Clive had become the new “nawab-maker.” The French government did not show any appreciation of the brilliant successes of Dupleix and he was unceremoniously recalled back to France in 1754 for “wasting too much investment on unprofitable ventures.” The last nail on the coffin of any design of French imperialism in India by Dupleix had been hammered by nonchalant French rulers in Paris. Dupleix lived out the rest of his years in disgrace and in oblivion.

Following the peace treaty the hostilities between the two rivals ceased for a while until another war erupted in Europe that saw them on the opposite sides again. The Seven Years’ War (1756 – 1763) spilled over to India but this time saw weakened French against a much stronger British force. Bengal became the casualty this time to Clive’s ambitions.

The Black Hole Tragedy and its aftermath

The British had fortified their position at Fort William in Calcutta, thus breaking their agreement with the Nawab of Bengal. When the wily Nawab Ali Vardi Khan died without a son, his impetuous twenty year old grandson Siraj-ud-daula became the Nawab of Bengal. He decided to march his army of fifty thousand on Calcutta. The thousand man British army had no chance and hence decided to largely flee. In the frantic stampede the vulnerable women and children were left behind with about 170 soldiers. That night on June 20, 1756, according to erroneous British report 146 English prisoners had been sequestered in the dungeons of Fort Williams and only twenty-three prisoners survived. This report of merciless death in the “Black Hole” of Fort Williams did much disservice to the British and Indian relationships that perhaps irreparably was damaged. There was little mention of the fact that the dungeons were built by the British to incarcerate their enemies in this foreign land. The true report recorded shows only 64 prisoners had been incarcerated and twenty one were alive in the morning. Siraj-ud-daula had not ordered the imprisonment or the torture though he was blamed for it. The furor over the prisoner death in captivity brought about a swift action from the British base in Madras.

Robert Clive, who now had risen in ranks to the position of Lieutenant Colonel, was once again dispatched. Siraj-u-daula was soundly defeated in the Battle of Plassey, where a mere 800 troops belonging to swashbuckling Clive defeated a fifty thousand strong army of the Nawab. Taking advantage of the hostilities in Europe, the British bombarded the French at Chandarnagar and captured the fortress on the river Hughli. Fort William in Calcutta was recaptured in January of 1757. The French were now totally removed from Bengal and Clive was the new de facto ‘nabob’ of Bengal, able to extract any price both in land and personal wealth.

The defeat of Siraj-ud-daula was assisted by his greatuncle, one Mir Jafar, who felt that he was deprived of the nawabship in Bengal after the death of his brother-in-law, Nawab Ali Vardi Khan. Mir Jafar soon was the elevated to Nawab of Bengal but found that he was ruling an empty shell of a kingdom. The real power was with the British, who amassed immense wealth without paying any taxes and effectively ruled the region without taking responsibility.

Beginnings of the British Raj

| History helped Clive as well. After the assault by Nadir Shah in 1739, the Mughal power had visibly dwindled. To add insult to injury, Shah Abdali, an Afghan picked up where Nadir Shah had left off, and attacked Lahore and Delhi repeatedly between 1748 and 1761. The Sikhs in Punjab, who were gaining prominence because of the Mughal weakness, only could harass the army of Shah Abdali as it returned with its plunder to Kabul but could not defeat it. |

|

The only power mighty enough to defeat any enemy at this time in Indian history was the Marathas. Peshwa Balaji Rao of Poona sent his brother Raghunathrao to Delhi to assist Nizam of Hyderabad’s grandson to secure his position in Delhi. Nizam’s grandson Imad-ul-Mulk, had designs about usurping the weakened Mughal Emperor and take power away from him. In this regard he was successful, albeit with the help of the Maratha army to provide security. Raghunathrao succeeded in driving the son of Shah Abdali from Lahore back into Afghanistan and Maratha power remained supreme. Shah Abdali returned to Delhi to win again, but was not interested in remaining in Delhi during its hot summer months. He placed a claimant of Mughal Empire, Shah Alam on the throne (whose father Alamgir II was hastily murdered by the grandson of the Nizam, as Shah Abdali approached Delhi). Wretched Shah Alam ruled Delhi for more than forty miserable years, until 1806, even after he was blinded by an Afghan in 1788. Mughal power was slipping into oblivion and this suited the British East India Company very well.

In 1760 Robert Clive returned to England as a rich man. He then bought precious stocks of East India Company (at 500 pounds each) in order to be in control of the directorship of the company. Thus Clive, who started as a lowly clerk in the company, and one bullet wound away from suicidal death, managed to amass a fortune in India, and now became the investor-owner of the company.

After 1761 Maratha power also got diluted due to infighting between the pentarchy of the Marathas (Gaikwad of Baroda, Holkar of Indore, Sindia of Gwalior, Bhonsle of Nagpur and the Peshwa of Satara). A large contingency of Maratha troops marched against the Abdali Afghans who were then in Delhi, savoring their plunder. The Muslim armies of Delhi, Audh and Bengal joined together and fought a jihadi battle against the Hindu infidel Marathas and defeated them in Panipat in 1761. Seventy five thousand Marathas were killed and another thirty thousand were taken as prisoner. Maratha dominance of both the North and South effectively ended in Panipat in 1761.

The French had already been weakened after the defeat in Bengal. They suffered similar fate in the south as well. Further advances by the British in the south resulted in a decisive victory against the French in Wandiwash in the south in 1760. A year later Pondicherry fell into British hands, but later returned as part of the treaty of Paris in 1763. However, Pondicherry’s fortifications had been breached and permanently destroyed and the French remained in India in a much weakened state from then on, without any wild ambitions of territorial gains.

By 1764 Bengal had been so rapaciously plundered by the British that the puppet Nawab could not take it any longer. The weakened Mughal emperor in Delhi and the rulers at Audh (which by now was an independent state) saw the writing on the wall, though too late. Their army was soundly defeated by the British forces and the diminished Mughal emperor sued for peace once again.

In 1765 Robert Clive returned as to govern Bengal. Though he could march to Delhi and take control of the heart of India, he played a cautious game. Taking a page out of Dupleix, from whom he had learnt the craft, he resorted to reap the benefits of the revenue from India’s heartland but not take the responsibility of governing it. He did not want to kindle the patriotic spirits of Indians or to damage their conscience at this juncture and risk losing the enormous power he had amassed in such a short period in this far off land. The British Raj had been established at least in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and an enormous sum was paid to the company from the coffers, tax free, in exchange for promise of no further military interventions. Mughal emperor Shah Alam was paid an annual compensation. The Company was officially a ‘diwan’ of the Mughals and thus was in charge of collecting revenue, under no obligation to pay anything to the Nawab of Bengal. With the chokehold and complete control of greater Bengal, the seeds of a British empire had been sown in India.

In 1765 Robert Clive returned as to govern Bengal. Though he could march to Delhi and take control of the heart of India, he played a cautious game. Taking a page out of Dupleix, from whom he had learnt the craft, he resorted to reap the benefits of the revenue from India’s heartland but not take the responsibility of governing it. He did not want to kindle the patriotic spirits of Indians or to damage their conscience at this juncture and risk losing the enormous power he had amassed in such a short period in this far off land. The British Raj had been established at least in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and an enormous sum was paid to the company from the coffers, tax free, in exchange for promise of no further military interventions. Mughal emperor Shah Alam was paid an annual compensation. The Company was officially a ‘diwan’ of the Mughals and thus was in charge of collecting revenue, under no obligation to pay anything to the Nawab of Bengal. With the chokehold and complete control of greater Bengal, the seeds of a British empire had been sown in India.

In 1772 Clive had been called back and replaced by Warren Hastings. Corruption among the company servants including Clive’s alleged abuse of power drew much criticism in London. Clive was kept busy for the next two years defending his actions (and his ill-gotten riches) in India in the British parliament. In 1774, Robert Clive at the age forty-nine successfully committed suicide at his home in London, an act that had eluded him as a young man of twenty-one, because of a malfunctioning handgun.

13-Nov-2005

More by : Dr. Neria H. Hebbar

|

Does the term 'Nabob' used in this script akin to 'Nawab' as we know ? |