Feb 13, 2026

Feb 13, 2026

The evening of Sunday, the 3rd of March 2002. The carefully manicured verdant sward of UDITA overlooked by soaring apartment blocks, providing occupants of the UDAYAN condoville a unique grandstand view of the multi-layered permanent open-air stage set against the shimmering cascade of a forty feet wide waterfall. The expectant crowd settles down, waiting for the performance. Lightning scars the night-blue sky; a heavy drizzle scatters the disappointed crowd. Some leave, but most stick on hopefully. Stars sparkle out a little later and the crowd reassembles. Dr Mallika Sarabhai steps up on stage in an ashram maiden's ochre robes to recount the astonishing concatenation of events that brought Darpana, Schubert and Shakuntala together.

The evening of Sunday, the 3rd of March 2002. The carefully manicured verdant sward of UDITA overlooked by soaring apartment blocks, providing occupants of the UDAYAN condoville a unique grandstand view of the multi-layered permanent open-air stage set against the shimmering cascade of a forty feet wide waterfall. The expectant crowd settles down, waiting for the performance. Lightning scars the night-blue sky; a heavy drizzle scatters the disappointed crowd. Some leave, but most stick on hopefully. Stars sparkle out a little later and the crowd reassembles. Dr Mallika Sarabhai steps up on stage in an ashram maiden's ochre robes to recount the astonishing concatenation of events that brought Darpana, Schubert and Shakuntala together.

In 1977, the German director Jorn Thiel, while making a documentary on Schubert for SDF TV, was handed a manuscript by the curator of a museum. Preoccupied with his work, Thiel put it aside in his car and forgot about it. When the car was sent for servicing, this manuscript surfaced and Thiel was astonished to find that it was an unfinished composition by Schubert entitled 'Sakuntala' (1820). Thiel took it to the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, who filled in the gaps. But who would stage the performance? Someone mentioned to him the Sarabhai mother-daughter duo. Serendipitously, as Thiel was changing trains in one station, he found himself staring at a poster: 'Mallika Sarabhai dances here today'. They met in October 1978. Early next year the performance was filmed.

What sets Mallika apart is her constant awareness that 'Time present and time past are both present in time future.' She is no Lady of Shallot spinning enchanting tapestries in an ivory tower, jealously guarding aesthetics from the rude touch of reality. Deliberately she took the audience out of the sylvan ambience to remind us all that here was a German Christian composer so inspired by a Hindu play that he bridged the civilizational chasm by music, while in Gujarat today Indians are slaughtering one another in the name of religion.

Dr Sarabhai introduced the theme as taken from Mahabharata without mentioning that it was Kalidasa's play and not Vyasa's original that inspired Schubert. Vyasa's heroine is a rare picture of a nubile orphan who is mature and self-assured enough to fight for her rights and plan out her future at the shortest notice, quick to grab Fortune by the proverbial forelock. She has nothing of the helpless, swooning romantic heroine of Kalidasa in her. Dushyanta is the opportunist, ever ready to grasp the easiest way out of a situation. The scenario is indeed vastly different from Kalidasa's romantic, hedonistic world. Moreover, Mahabharata is not just a man's world. It is the women who mould its men. In the Epic-of-epics, through the murky fog of the noisome fumes of lust, hatred, ambition and greed, we glimpse a few statuesque figures radiating beauty, power, grace and an inflexible determination: Devayani and Sharmishtha, lust-crazed Yayati's unforgettable queens who create the dynasties that rule the country; Ganga and Satyavati, ruling over doting Shantanu and deciding the fate of the kingdom; Gandhari and Draupadi, loser and winner in the holocaust but both surrounded Niobe-like by the corpses of their children and brothers; Kunti, raising five heroes alone yet, curiously, leaving them after the pyrrhic victory to welcome death in a forest-fire. Perhaps the most significant of them is Shakuntala, for our country takes its name from her son Bharata.

Vyasa's Shakuntala arrives with her son to confront the king who remembers all, yet denies her. She launches a frontal attack on him that contains the most direct utterances in Indian tradition on a wife's status. One expected that Mallika, with her commitment to women's empowerment, to have incorporated these in her presentation:

A wife is a man's half;

A wife is a man's closest friend;

A wife is Dharma, Artha and Kama;

A wife is Moksha too;

A sweet speaking wife is a companion in happy times;

A wife is like a father on religious occasions;

A wife is like a mother in illness and sorrow; '

A man who has a wife is trusted by all;

The wife is a means to a man's salvation'

No man, not even in anger, should displease his wife;

Happiness, joy, virtue, everything depends on her.

She is the hallowed soil in which he is born a second time.

--[Sambhava Parva, 74.40, 42, 43, 50, 51]

When Dushyanta insults her parents, Vishvamitra the Kshatriya-turned-rishi and Menaka the celestial nymph, as lustful and abuses her as a slut, Shakuntala's indignation flares up in a splendid flash of pride:

My birth Dushyanta is nobler than yours.

You walk on earth, I roam the sky. [82-83]'.

A pig delights in filth even in a flower garden;

A wicked man finds evil even where there's good [89]

She ends with a calm prophecy of her son's inevitable succession to Dushyanta's throne even without his help. Later, the king explains that he had decided against accepting them because his subjects would have suspected him and not considered his son of pure birth [sloka 116].

Kalidasa's Abhinjnanasakuntalam (The Recognition of Sakuntala) was translated into English by Sir William Jones in 1789. Jones first came to hear about Indian Natakas during his sojourn in Europe in 1787. He began to investigate these on his return to Calcutta. Pandit Radhakant pointed out to Jones the similarity of these Natakas to English plays staged in Calcutta and, as an example, gave him a Bengali recension of Sakuntala. Ramlochan, a Sanskrit teacher of Nadia, helped Jones read the play and in 1789, Joseph Cooper published the English translation of Sacontala. The impact of this work was soon felt in Europe. By 1791, Sacontala was translated into German by Forster and by 1792 into Russian by Karamsin. Translations in Danish (1793), French (1803) and Italian (1815) appeared soon after. In particular, Goethe was deeply influenced by the play, as he wrote in a letter:

"The first time I came across this inexhaustible work it aroused such enthusiasm in me and so held me that I could not stop studying it. I even felt impelled to make the impossible attempt to bring it in some form to the German stage. These efforts were fruitless but they made me so thoroughly acquainted with this most valuable work, it represented such an epoch in my life, I was so absorbed it, that for thirty years I did not look at either the English or the German version...It is only now that I understand the enormous impression that work made on me at an earlier age."

No wonder he modelled the jester in the prologue of Faust (1797) on the vidusaka in Abhinjnanasakuntalam as noted by Heinrich Heine. Goethe's friend Schiller wrote of the play, "In the whole world of Greek antiquity there is no poetical representation of beautiful love which approaches even afar."

But what of Schubert's composition? Here is an extract from a posting on the World Wide Web:

'DISORIENTED EXPRESS Issue 52-A 14th February 2000, e-mail address: metzke@san.rr.com

Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828), one of the great men of classical music but also one of the greatest failures in music history in the realm of the theatre. He wrote, or started to write, sixteen works for the stage. Only two were ever performed in his lifetime, and none holds the stage today. Half a dozen were left unfinished, usually because they were rejected by the Viennese opera management even before the music had been completed. And such is the case with the present case, "Sakuntala," a fragment begun in 1820 but quickly abandoned - only a few sketches remain - when the play on which it was based was essentially laughed at by opera management. Schubert wrote wonderful music, but he had absolutely no sense of drama. The play has not survived so we have no idea what it was about, and no way of knowing just how bad it was, but apparently it was pretty awful. It remains to this day the one and only Schubert stage work of which not one note has been performed for the public, anywhere, ever. (One would guess from the title that it was probably one of those faux-Turkish silly comedies so popular in that era, with slaves or captured Crusaders falling in love with concubines or Ottoman princesses. Half the composers in Europe did one of those. Two or three aren't bad. Mozart's "Abduction from the Seraglio" is the best. Mostly they are utter rubbish.)'

What the play was about is quite apparent to anyone who has heard of Kalidasa. Our Internet correspondent is ignorant of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra having performed this 'pretty awful' piece, and of the remarkable impact it creates on any audience when choreographed inimitably by Mallika Sarabhai.

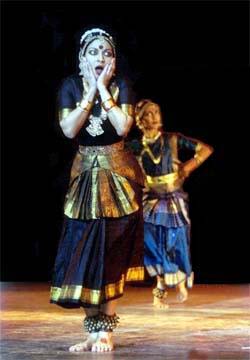

The Kolkata crowd watched enraptured that March evening an amazing use of the landscape in Mallika's choreography that had taken her just two hours to finalise. Once the performance began, its impact was so magnetic that almost immediately the entire crowd moved forward to get closer to the massive stage. Last year she had performed at Daulatabad fort. In UDITA every depression, elevation, flight of steps, the entire meadow was used with remarkable imagination to create the forest, Rishi Kanva's ashram, Dushyanta's wooing of Shakuntala, the royal palace and courtroom, Shakuntala oblivious of Durvasa's fury loosing the signet ring while bathing, the fishermen netting their catch (Mallika's son Revanta performed the role of the fisherman who cuts open the fish and hands over the ring to the king), and finally Dushyanta's discovery of his rejected beloved and their son Bharata (played by Mallika's daughter). The finale came with a striking torch-lit procession in the surrounding darkness that accompanied the reunited couple and their son to their palace.

An extremely unusual fusion of Western opera music and Indian classical dance incorporating ballet movements, it brought to life every nuance of the major incidents of Kalidasa's play through mudras and miming. Even the bee from which Dushyanta rescued Shakuntala, the fawn and each plant and vine from whom she took leave'all were figured forth in Mallika's exquisitely sensitive and graceful dance. Kept to an absolute minimum, the voice-overs in Sanskrit, such as Durvasa's curse, had a resounding impact.

A single viewing is just not adequate to take in the beauty of the production. The very amplitude and massive dimensions of the open-air stage militate against an instant appreciation of the multifarious nuances and delicate touches that scintillate in Mallika Sarabhai's production. That evening the truth of Goethe's apostrophe came home to me:

Would you the young year's blossoms and fruits of it's decline,

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted and fed,

Would you the earth and heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name you, O Sakuntala, and all at once is said. (1791)

17-Mar-2002

More by : Dr. Pradip Bhattacharya