Feb 08, 2026

Feb 08, 2026

By 500 BC, Vedic society was slowly stratifying into a rigid class system of the familiar four Varnas which exist in some form in Indian society even today - the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. The former, being the priestly class, were gradually assuming dominance over society with a tenacious grasp over tedious rituals that controlled every aspect of life. This added a superfluous complication to the busy life of an increasingly urban social fabric.

In stepped two major reformers, Gautama and Mahavira, They made an impact on this scene when, almost contemporaneously, they founded new doctrines based loosely on existing Hindu precepts but denying the role of the priests as media between Man and God. In fact, Buddhism held that only the soul was of import - God was a metaphysical construct of Man's mind. Buddhism was destined to have mass appeal worldwide. Yet at the crucial point of its nascence, it was fortunate to initially receive the patronage of the mercantile class, and later, of a king who would provide vital support - Ashoka the Great. Ashoka proclaimed Buddhism as the state religion and spread its message to the four corners of the land through state-funded monasteries, grants, and his famous rock-edicts, which dot the face of modern Orissa and central India.

After Ashoka, by 200 B.C., the royal patronage enjoyed by Buddhism was on the wane. Gradually, under a succession of kings, Brahmanism regained the prestige it used to enjoy. Under the circumstances, Buddhist monks retired from urban conglomerates to secluded spots, where they built their places of worship and in general led a life of penance and meditation. However, assistance from the mercantile class, who had little interest in Brahmanism, was still available, and thus the Buddhist monks could, over the years, transform their humble centers into truly magnificent works of art. The foremost among these centers was Sanchi, near modern Bhopal. Here craftsmen labored for over a hundred years to make Sanchi a point of pilgrimage for devoted Buddhists and scholars from all over Asia for centuries. The magnificent ruin still attracts a large number of tourists today.

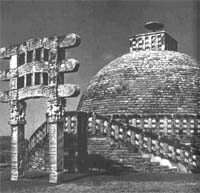

After Ashoka, by 200 B.C., the royal patronage enjoyed by Buddhism was on the wane. Gradually, under a succession of kings, Brahmanism regained the prestige it used to enjoy. Under the circumstances, Buddhist monks retired from urban conglomerates to secluded spots, where they built their places of worship and in general led a life of penance and meditation. However, assistance from the mercantile class, who had little interest in Brahmanism, was still available, and thus the Buddhist monks could, over the years, transform their humble centers into truly magnificent works of art. The foremost among these centers was Sanchi, near modern Bhopal. Here craftsmen labored for over a hundred years to make Sanchi a point of pilgrimage for devoted Buddhists and scholars from all over Asia for centuries. The magnificent ruin still attracts a large number of tourists today.  The Sanchi Stupa basically is a dome, surmounted by a finial or 'harmika', with a circumambulatory path around it, delineated by a railing or 'vedika'. As mentioned earlier, the spherical shape of the Stupa was a structural culmination of rubble masonry piled up, and also had metaphysical connotations with the apparent shape of the universe. The harmika on top represented the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha first gained enlightenment. And the path around provided a passage for monks who could circle the Stupa, chanting endlessly.

The Sanchi Stupa basically is a dome, surmounted by a finial or 'harmika', with a circumambulatory path around it, delineated by a railing or 'vedika'. As mentioned earlier, the spherical shape of the Stupa was a structural culmination of rubble masonry piled up, and also had metaphysical connotations with the apparent shape of the universe. The harmika on top represented the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha first gained enlightenment. And the path around provided a passage for monks who could circle the Stupa, chanting endlessly.  It has been observed (Satish Grover, 1980**) that the chaitya hall evolved due to the fact that the Sanchi Stupa was an outdoor structure - not permitting use in inclement weather. Hence the evolution of the chaitya as a sort of indoor Stupa. However, this reason seems to be a trifle strange - totally against the ethos of the monks of a life of penance and hardship. The author surmises that the chaitya served the purpose of a 'minor deity', so often found in large Hindu temples, where niches hold images of 'lesser' gods. The Buddhist monks, still a part of predominantly Hindu society, expressed this subconscious desire by building a number of chaitya halls around the main Stupa.

It has been observed (Satish Grover, 1980**) that the chaitya hall evolved due to the fact that the Sanchi Stupa was an outdoor structure - not permitting use in inclement weather. Hence the evolution of the chaitya as a sort of indoor Stupa. However, this reason seems to be a trifle strange - totally against the ethos of the monks of a life of penance and hardship. The author surmises that the chaitya served the purpose of a 'minor deity', so often found in large Hindu temples, where niches hold images of 'lesser' gods. The Buddhist monks, still a part of predominantly Hindu society, expressed this subconscious desire by building a number of chaitya halls around the main Stupa.

04-Jan-2001

More by : Ashish Nangia