Mar 11, 2026

Mar 11, 2026

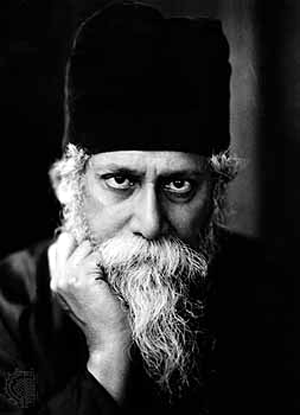

When Rabindranath was born 150 years ago in

When Rabindranath was born 150 years ago in

About

He was yet to win his freedom. It came with his journey with his father to the

What was his attitude towards nature? According to him man is an integral part of nature. Let us refer to two famous poems Sukh and Madhyahna from the collections Chitra and Chaitali respectively, published in boloji in my translation as Happiness and The Noon. Both were written during this period. Here are the links - https://www.boloji.com/poetry/1301-1400/1350.htm and https://www.boloji.com/poetry/1500-1600/1591.htm. To elucidate this the concluding lines of Madhyahna are reproduced below –

In the midst of all these

I am a stranger

Yet I do not feel estranged

I feel I am one of them

It also seems

After a long time

I have returned

To my own native place

I have gone back in time

To my former life

To that fresh morning

When like an infant

Clinging on to its mother's breast

I was inseparably mixed

With land, air, water and the sky

And along with all living beings

That thrive on this earth

I was joyously sucking

The elixir of my first existence.’

And nearness to nature is nearness to God. That is what he says in the poem Palligrame from the collection Chaitali, also published in boloji in my translation –

In The Country

Here I get him closest to my heart –

As close is the earth beneath my feet

As are close to me

The fruits, flowers and the air and water.

Here I love him too

As I love the songs of birds

The murmur of streams

The mellowness around

The light of dawn and the greeneries of trees.

Here I find him beautiful

As the evening is beautiful

As the fragrance of flowers filling the night

And the dew-drenched morning

With its clean air

And a lone star in its sky.

Here he is dear to my heart

As the rain water dropping from the sky

The sweet sleep of night

The water of rivers

And the cool shade of trees.

Like the tears trickling down my eyes

Here my song flows with ease.

Here his love fills my heart

As life fills all my limbs.

Examples can be multiplied from his writings, here only some of those poems which are available in translations on boloji have been cited. A few more links are given below.

All These I loved

https://www.boloji.com/poetry/2801-2900/2893.htm

Akash bhara surya-tara

https://www.boloji.com/poetry/3601-3700/3697.htm

Evening

https://www.boloji.com/poetry/3001-3100/3050.htm

The Music of the Rains

https://www.boloji.com/poetry/4001-4500/4205.htm

The Call of the Far

https://www.boloji.com/poetry/4501-5000/4528.htm

Most significant are his songs written exclusively on the seasons. They are about 283 in number and all of them were set to tune by the poet himself. He introduced the celebration of different seasons when accompanied with dancing these songs were sung. Perhaps in world literature they have no parallel. Tagore rarely, if ever, boasted about his writings, but his songs were a different matter. He once said that everything else of his writings may be forgotten but his songs will never die. One has only to listen to his wonderful songs to know how eminently he was justified in making such a large claim. Let us conclude by quoting one rainy day song in my translation, also published in boloji under the caption – My friend, come in these rains – which was recited in the poet’s prose translation by W.B.Yeats during the reception given to the poet at Trocadero Restaurant in

My friend, come in these rains

On this misty overclouded rainy day

Evading all

Like silent night

In stealthy steps you have come.

The morning has closed its eyes

The wind is hopelessly sighing

And the blue naked sky

Is overcast with endless clouds

In the woodland the birds do not sing

In every home the doors are closed

You are a lonely wayfarer on a lonely road.

Now you are alone, O my dearest friend,

My doors I have kept open

Ignoring me

Like a dream

Please don’t glide past my home.

-------------------------

Transcreation of one of the sweetest rainy day songs – Aji shravanghanagahan mohe/gopan tabo charan phele/nishar mato nirab ohe/sabar dithi eraye ele – by Rabindranath Tagore. Best recording of this song is by Debabrata Biswas.

|

|

Dear Index, You may very well do so with the permission of the editor of boloji. |

|

|

Dear Dr. Mallick, Thanks for visiting my blogpage and reading the translations. |

|

Dear Kumud, well I have been reading all your translations of Tagore poems. You have created a niche for yourself by your dedication. Thanks. |

|

Dear Mouri, Very happy to know that all your time is not taken by your naughty son and your work - you have time to spare for the things of the mind. And don't forget the films. |

|

Enjoyed this write up immensely! Thank you for sharing this with us at Boloji. |

|

Dear Dipankar, My condition you can compare with a fly that has fallen into a pot full of honey. Thanks for your appreciation of my modest efforts. |

|

Dear Kumud-babu: Finally I got the chance to read your second blog post. I have to admit that I was not aware of all the details that you have brought out, though I have had some exposure through chhinna-potraboli and other writings. And, of course, through his songs dedicated to nature. The depth as well as breadth of Tagore is, to say the least, mind boggling. I admire your one track dedication -- the endless love for the man -- the uncompromising desire to present him to the world. I do wish you the success that you richly deserve. In trying to translate Tagore, I have often felt that he defies translation. He defies translation not because of a language barrier. He defies translation because he was too deep a thinker to be translated. Nonetheless, at least the language barrier should be removed between him and the rest of the world. I am hoping to learn a lot from your blog. Your knowledge and reading of Tagore is vast and increases the thirst in any sensitive soul. Wishing you all the best. Dipankar |

|

Thank you Mr. Ghosh for your appreciative comments. Compared to the vast works of Rabindranath his writings available in English translation is very negligible. It is the moral obligation of his fellow Bengalis to make him available to those who cannot reach him because of language barrier. In my first blog 'Meeting Rabindranath' I have invited you all to explore the poet. To my modest efforts I would request to join yours too. |

|

A very nicely researched article. I admire the writer's dedication on Tagore. Have read quite a few of poetry transcreations and it has helped me to understand Gurudev better. |