Mar 13, 2026

Mar 13, 2026

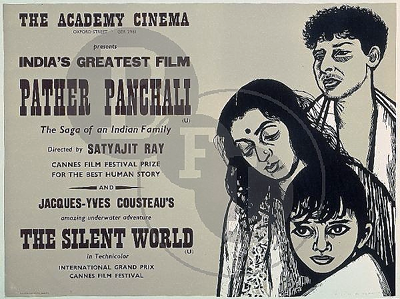

Pather Panchali, inspite of its stark depiction of extreme poverty is never morbid. Nor is it ever dull. And the reason for this is its lyrical treatment of the beauty of rural Bengal, and its dramatic and humourous interludes. The director takes care to show that even midst severe deprivation, life can be intensely enjoyable, and that love can add sparkle to the most humdrum existence.

Pather Panchali, inspite of its stark depiction of extreme poverty is never morbid. Nor is it ever dull. And the reason for this is its lyrical treatment of the beauty of rural Bengal, and its dramatic and humourous interludes. The director takes care to show that even midst severe deprivation, life can be intensely enjoyable, and that love can add sparkle to the most humdrum existence.

Pastoral Lyricism

Durga is introduced through a long shot.

We barely catch a glimpse of her as she scampers off. She skips through the bamboo grove, almost like a spirit of the grove, one with nature,as she hides behind a lotus leaf, peering surreptitiously at her mother. The background score, lilting and sweet, establishes the lyrical nature of the film. The music underscores Durga’s carefree nature.

We barely catch a glimpse of her as she scampers off. She skips through the bamboo grove, almost like a spirit of the grove, one with nature,as she hides behind a lotus leaf, peering surreptitiously at her mother. The background score, lilting and sweet, establishes the lyrical nature of the film. The music underscores Durga’s carefree nature.

The next time Durga appears as a child of nature, she is older and now a didi. Apu, she and the dog follow the sweet-seller through the village. As they pass the pond, their reflection merges with that of the trees on the embankment. A wind ripples through the pond. They traverse through fields, a composite trio, scattering the ducks that flock around the arched gateway of sejo-thakrun’s house.

A dusk sequence best illustrates the lyrical quality of the film. As dusk falls, the cows come home.Women in the village pay obeisance to the tulsi; the camera tracks to Harihar and Apu studying under the light of the lamp. Indir tries stitching together her threadbare shawl. Sarbojaya ties Durga’s hair. And then...Apu asks Durga about the train. The entire sequence showcases the quiet harmony that settles down on a village household once night falls.

Indir singing a bhajan in the hushed stillness of the night is another poignant moment of lyrical beauty.

Lyricism in the film reaches a climax in the rain sequence. First there is the roll of thunder, followed by a rapidly darkening sky. Banana leaves start swaying the in the breeze. Apu rushes home to fling his books through the window and race out into the open fields. Lotus leaves start dancing in the pond. The first drop of rain falls on the bald pate of a man who had dozed off while fishing in the pond. This is immediately followed by a rapid pitter-patter of raindrops on the pond. We see the dog running home and shaking himself dry. In direct contrast Durga rushes outside and revels getting drenched to her skin. Soon the rain comes down in a torrential downpour. Brother and sister huddle together under the tree. Sarbojaya returns home and on the sly picks up a coconut that had fallen to the ground in the rain (ironical since she had repeatedly rebuked her daughter for the very same act). The sequence communicates solely through visuals and Ravi Shankar's background score, based on raga Desh.

Love

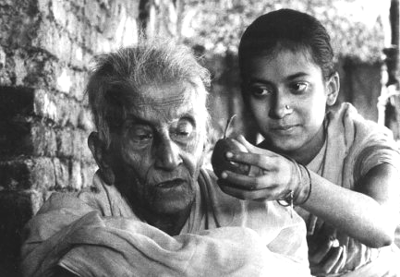

Durga and her old pishi Indir, share a most deep, abiding love that defies threats of severe disciplining by Sarbojaya. Durga steals for her pishi because she knows her mother grudges her any extra delicacies from the kitchen store. The warmth of the smile that lights up pishi’s face when she discovers the guava that Durga has got for her envelops the little girl. When pishi has a hearty meal, Durga watches her with a quiet contentment. There is so much unspoken camaraderie between the two, seen most when pishi rushes to defend Durga from her mother’s blows.

Durga and her old pishi Indir, share a most deep, abiding love that defies threats of severe disciplining by Sarbojaya. Durga steals for her pishi because she knows her mother grudges her any extra delicacies from the kitchen store. The warmth of the smile that lights up pishi’s face when she discovers the guava that Durga has got for her envelops the little girl. When pishi has a hearty meal, Durga watches her with a quiet contentment. There is so much unspoken camaraderie between the two, seen most when pishi rushes to defend Durga from her mother’s blows.

When pishi returns the first time, after a quarrel with Sarbojaya, Durga keeps Pishi’s belongings in her room with a proprietary air about her. Pishi is back where she belongs. Pishi and Durga are a pair, communicated visually as two faces framed together as pishi looks down at her new born nephew. When Sarbojaya beats up Durga and throws her out of the house, it is pishi who gathers the useless baubles that lie scattered on the floor, all of Durga’s worldly possessions.

Ranu, of the Mukherjee household, and Durga’s friend lights up Durga’s life with her sweetness and compassion. She never begrudges Durga a tasty titbit and acts peacemaker when the children start squabbling at the picnic. When she gets married, Durga weeps at losing her closest friend. Her bond with Durga is the only close relationship that Durga has with someone of her age. Her other two closest relationships are separated by considerable years; one with Apu, and the other with the doddering Indir.

Drama

The first scene begins with a theft; minor no doubt, but it generates sufficient drama. The wealthy and irate sejo-thakrun tries to intercept the little thief but fails.The object stolen is a guava, which will bring such joy to Indir Pishi, but will eventually lead up to the confrontation scene between Sejo-thakrun and Sarbojaya, climaxing in the terrifying thrashing that Durga receives from her mother.

The scene in which Durga is dragged by her hair and beaten for stealing begins with a most dramatic entry. Apu is playing with his bow and arrow. His arrow falls near the main door. As he runs to pick it up the door is violently pushed open and sejo-thakrun is framed by the door. The impact is almost menacing – as if an ogre is about to descend on the peaceful inhabitants of this hut. Sarbojaya’s anger at Durga is particularly frightening because it is such a cold fury. Each person’s response to her fury makes the scene all the more dramatic. Durga cowers in fear and pain; Indir hobbles across desperately trying to protect her niece from the merciless blows that are raining down on her; Apu watches numb with terror. After Durga is thrown out, Indir quietly gathers Durga’s baubles lying scattered on the ground, giving us a much needed breather, a lull after the storm has blown over.

Interestingly the incident of stealing the fruit, introduced so early in the film, is also a critical plot point. Other than Hariharan’s uncertain employment, it is Durga’s reputation as a thief that causes the most upheavals in the story. It is what causes Sarbojaya to drive out the old and frail Inder from her house, for it is she, so feels Sarbojoya, who is corrupting her daughter. The movie ends with Apu discovering the necklace Durga had been accusing of stealing. An innocent,childish act of wanting to possess someone’s else’s pretty trinket, but it bookends the film as it were: the film started with Durga being accused of theft; it ends with Apu, and with him, us, the audience discovering, that Durga is indeed what the nasty sejo-thakrun had accused her of being, a petty thief.

A recurring motif in the film is one of the thrill of discovery. Whether it be Durga’s little treasure troves, or Durga prying Apu’s eyes open through a tear in the sheet,or the most magical of them all, the wonder of a train whistling and chugging along through a field full of kaash phool, the joy of discovery casts a veil of romanticism over the lives of Durga, Apu and their old pishi. Durga’s various hidden treasures are shot in a manner that make them appear mysterious. Whether it be her pishi’s earthen bowl, or the recess in which she hides the kittens or the coconut shell, each of them reveal their secrets with a heightened sense of drama. The earthen bowl just holds a few bananas and a guava, but the camera dwells on its dark, cavernous interiors, piquing our interest and curiosity – what was it about to reveal!

When Durga peers into the earthen jar, in which she had kept the kittens, there is an extreme close up of her face. We don’t see what it is she is smiling at.When she pulls out the kittens, for a moment one fears she might be nursing something dangerous. Would she be pulling out snakes from within the dark, humid earthen jar tucked away in the corner of the garden patch? As she brings out the kittens, the sky is projected in the background, a perfectly poetic pastoral composition– child, animal, nature, in one tightly shot frame.

When Durga peers into the earthen jar, in which she had kept the kittens, there is an extreme close up of her face. We don’t see what it is she is smiling at.When she pulls out the kittens, for a moment one fears she might be nursing something dangerous. Would she be pulling out snakes from within the dark, humid earthen jar tucked away in the corner of the garden patch? As she brings out the kittens, the sky is projected in the background, a perfectly poetic pastoral composition– child, animal, nature, in one tightly shot frame.Train scene

In Act I, Durga and her pishi are accomplices in crime, enjoying the joys of forbidden fruit! In Act 2, Apu replaces pishi as Durga’s co-conspirator. Together they lick some tamarind paste, prepared in secrecy by Durga. Their many surreptitious escapades break the monotony of their otherwise humdrum lives. Thus, they trail the sweet-seller, through the bamboo grove, across the fields and the village pond, right up to the sejo-thakrun’s mansion, another day well-spent for they end up getting a free sweet and get to play with their friends in the mansion.

Their most exciting adventure is the day spent in the fields when the spot the train for the first time. In the story-telling scene, all three, pishi, Durga and Apu escape together to an imaginary world of princes and demons, pishi’s shadow looming ominously over them, while she whispers the story to them in exaggerated, conspiratorial over tones.

Their most exciting adventure is the day spent in the fields when the spot the train for the first time. In the story-telling scene, all three, pishi, Durga and Apu escape together to an imaginary world of princes and demons, pishi’s shadow looming ominously over them, while she whispers the story to them in exaggerated, conspiratorial over tones.

The rhythm of the film is slow, with deliberate long pauses, but it never sinks into dullness for Ray interjects joyous rapid activities to dispel any feeling of torpor. One such scene is when Durga chases Apu for stealing her tinsel paper to make himself a crown. In and out they weave out of the broken-down wall, each outsmarting the other, until Durga finally catches Apu and hits him. To teach him a lesson she runs off into the fields, leaving him behind. Not being able to bear the thought of losing his closest companion, Apu runs after his sister.Another scene of similar sprightliness is the bioscope scene in which the children crowd round the bioscope man to see the wonders of India.

Indir’s comings and goings mark moments of heightened emotional drama in the story. The first time she leaves, it is because Sarbojaya accuses her of spoiling her daughter.She returns to celebrate the birth of her nephew, Apu. The second time she leaves it is because of another scathing verbal onslaught by Sarbajoya who resents that Indir had begged a shawl from her other relative. Couldn’t she have waited until her nephew got her one, she rebukes Indir? Did she care only about her own comforts? The third time she returns, it is to die. She begs for a place to rest her tired, ailing bones.Sarbojaya turns her out of the house. Indir dies all alone, without a soul to ease her intense discomfort as she takes her last gasp of breath.

Durga discovering her dead aunt is one of the most dramatic moments in the film, more so because it contrasts so strikingly with the preceding scene, the train scene. The train scene is magnificent – larger than life, both visually and aurally, beyond comprehension to the children. Indir’s death scene is very intimate and after the thundering of the train, very still and silent, and yet it is equally dramatic in its impact. Durga thinks her aunt has fallen asleep in the bamboo grove. She shakes her gently and then more vigorously. The audience waits with baited breath – at which moment would Durga realize her beloved pishi was no more? Indir falls with a thud on the ground. Her water pitcher, her only constant worldly possession, other than the tattered mattress she carried with her everywhere, rolls off the grove and drifts away into the pond. A beautifully composed scene that combines drama, lyricism and symbolism, an example of how Ray weaves magic around his scenarios.

Humour

Gentle humour interlaces and uplifts the sombre mood of the film. Instances such as:

Though Aparajito is considered a greater film, my personal favourite is Pather Panchali. Aparajito lacks the myriad hues of Pather Panchali. The lyricism of the beauty of rural Bengal, the joy of discovery and the poignancy of unrestrained love among children and sorrow that is mitigated by the innocent forgetfulness of childhood, all this makes Pather Panchali linger on in our minds and hearts, long after the film has ceased to play.