Nov 04, 2025

Nov 04, 2025

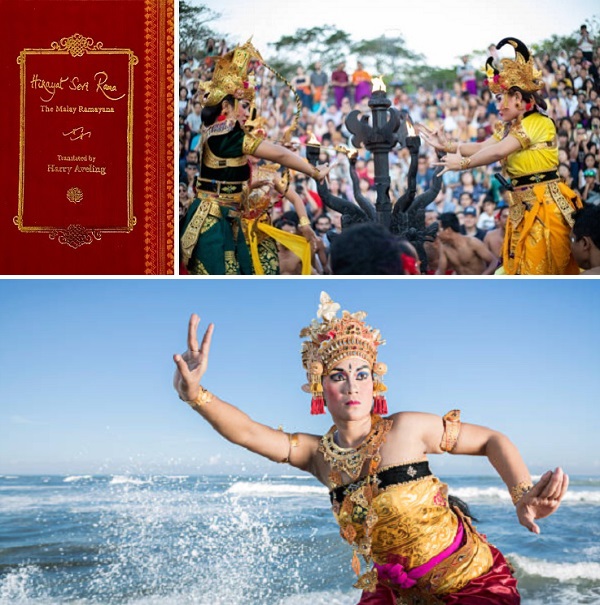

Hikayat Seri Rama, The Malay Ramayana, Harry Aveling (tr.), Writers Workshop, Kolkata, 2020, p. 287, Rs. 900.

The remarkable story of the ‘Indianisation’ of South-East Asia is an instance of historical spontaneity. It was not a result of the imperialistic ambitions of any Indian king. The invasions of Rajendra Chola (1025 AD) and his son, Virarajendra Chola (1068 AD) were not motivated by any expansionist design. These were the results of the rivalry between the Cholas and the Sailendras of South-East Asia to gain supremacy over the maritime trade routes. Besides, these came quite late into the Hindu/Buddhist period in the history of South-east Asia. Hinduism and Buddhism travelled to South-East Asia following the footsteps of the indomitable traders. The traders reached these countries through the sea-route as well as the land route. They were followed by many adventurers and priests. They married local girls and settled down in the peninsula and the islands. They took with them their religion and culture. The native population accepted the new religions and culture with great enthusiasm. The Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, became an important part of their own cultural tradition.

It is not possible to determine exactly when this process of Indianisation began. The earliest encounter between South-East Asia and India began in very ancient times. Both were strong maritime nations. Both had excellent ports and powerful ship-building industries. Traders of both these countries were skilled navigators. Consequently, India and South-East Asia had a significant commercial link with each other. R.C. Majumdar observes, “… trade and commerce must have been a supreme passion in the centuries immediately preceding and following the Christian era.” In fact, South-East Asia and its prosperity was quite well-known in India from much before the Christian era. Even in the Ramayana itself, there is mention of these islands. Sugreeva instructs Vinata, the leader of the team of vanaras going eastwards in search of Sita, to go “… to Yavadvipa, splendid with seven kingdoms and embellished with gold mines.” (Critical Edition, 4.39.28-30). Emperor Ashoka sent Soma and Uttara as preachers to South-East Asia. Reference to Suvarnadvipa and Suvarnabhumi is found in many pre-CE books, e.g., Arthashastra, Jatakas, Milinda Panha, etc. Mahaniddesa, a Pali canon, refers to the difficult journey of sailors to these islands which are named according to the items of their trade, - Rupyakadvipa, Tamradvipa, Yavadvipa, Karpuradvipa, etc. Even in Tamil Sangam Literature, in a love poem named, Pattinappalai, we find reference to these prosperous islands. Kathakosha has reference to these islands. We find mention of Suvarnadvipa in later works too, namely, Vrihatkatha, Kathasaritsagara, etc. Interestingly, Atisha Dipankar Srijnan, an eminent Buddhist scholar of 11th century, studied under the guidance of Dharmakirti at Suvarnadvipa (Sumatra).

Therefore, it is difficult to establish a timeline for the cultural absorption of Indian lifestyle in the South-East Asia. Politically it is seen that by the first century AD, kings with Sanskritised names are ruling at many places. This trend continued till the 13th century. All the kings who ruled Burma, Malaya, Siam, Cambodia, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Bali, etc. had Sanskrit names. During this time span, the amazing Hindu and Buddhist temples were built by these kings, depicting stories from Ramayana and Mahabharata on the walls. By the 9th century we find the profound impact that Indian culture exerted on the way of life in South-East Asia in every field, namely, writing, language, literature, religion, philosophy, politics, law, architecture, sculpture, etc. But this influence did not displace anything local. It was never perceived as a threat. It blended with the local traditions. It merely helped to enrich and enlarge. Just as the Indian traders and travellers took the Indian cultural traditions to South-East Asia, the sailors from those countries too came in contact with Indian customs religions, literature, etc. during their visits to the Indian ports and carried those back to their countries. This free and intimate intercourse between the two races resulted in a gradual and spontaneous fusion of two cultures.

Of all that went from India to South-East Asia what impressed the South-East Asians most were perhaps the two Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. These permeated all walks of their life. They made their way into their social customs, religion, literature, folklore, art, sculpture and architecture. In time, they had their own Ramayana and Mahabharata. It must be noted that in the beginning, these were orally transmitted. Therefore, as these travelled through space and time, the narratives absorbed the customs, folklore and social traditions extant among the South-East Asians. Even after these were written down, changes kept creeping in prompted by the inclinations and background of the copyists. It is not really surprising as the same thing happened in India too where we have a plethora of different versions of the epics, quite different from the originals. Consequently, the epics available in South-East Asia are not really as we know them here though the main frames remain the same. Since we are discussing the Ramayana extant in Malaya, we shall limit our discussion to the Ramayana only.

Ramayana too underwent changes here. It included local stories and incorporated many non-Valmiki lores which, as mentioned earlier, the sailors heard during their visits to the Indian ports and also brought in by Indian traders and travellers. As a result, we have Rama Zadtaw (oral) and Rama Thagyin (written) in Burma, Ramakien in Thailand (Siam), Reamkien in Khmer, Ramakirti in Kambodia, Phra Lak Phra Ram or Pha Lak Pha Lam in Laos (there is no ‘R’ in modern Lao), Ramayana Kakawin in the Indonesian archipelago, Ramacavacha in Bali and Hikayat Seri Rama in Malaya. Also, we have Phra Ram Sadok in Laos which is a Buddhist version following the Jataka tales. Even in the Philippines, there is a Rama story, named, Maharadia Lawana.

Due to their frequent contact with Arab traders and their burgeoning influence, the South-East Asians were impressed with Islam. Frequent visits by Muslim priests, mainly Sufis, from the Indian mainland also helped in the quick proliferation of Islam in South-East Asia. Many kings accepted Islam and the people too adopted the new religion as eagerly as they had accepted Hinduism and Buddhism. Islam too blended into the local culture smoothly. By the early 16th century, the Islamisation of South-East Asia was more or less complete. Interestingly, though the religion changed, cultural traditions did not. The epics continued to dominate the cultural life of the inhabitants, but to honour their new religion, they brought in certain minor changes: “…the text was written down for a Muslim court... which was still conservative enough to like the old tales of the Hindu period, provided they were presented in a form which Muslim pundits could condone.” The author also assures that, “I shall delete anything that is bad.” The title itself became Arabic, Hikayat Seri Rama, meaning ‘The Story of Sri Rama’; the script was Arabic; the Hindu Triad was replaced by Allah and his prophet was named Adam/Nabi. Besides that, very few Islamic changes were introduced in the narrative – Rawana is blessed by Allah through Nabi Adam, Sita asks Hanuman to pay his respects to the stone on which Nabi Adam landed on earth, the roots, leaves and the bark of the tree planted by Nabi Adam are used as medicine to revive Rama and Dasharatha is the great-grandson of Nabi Adam.

Harry Aveling, the translator, informs us, “The translation offered here is based on an edition of the Malay manuscript from Acheh in North Sumatra, presented in 1633 by the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud to the Bodleian Library at Oxford.” This was edited by Rev. W.G. Shellabear, published in 1915 and romanised by Wahi Bin Long in 1964. It is interesting to note that this Malayan manuscript was brought to England by an English sea-captain from Acheh in 1612. How Archbishop Laud got hold of it is not known. The other important manuscript was edited and published by P.P. Roorda van Eysenga (1843). There are two other manuscripts available, namely, the Wilkinson Manuscript and the Raffles Malay Manuscript. It must be understood at the outset that, “The Malay Language has long had a role of a lingua franca in maritime South-East Asia. When we reach the twentieth century, the Indonesian nationalist movement adopts it as the national language of Indonesia. Bhasa Indonesia is the Malay language with variations reflecting local language and evolution.” (M. Saran and V.C. Khanna, The Ramayana in Indonesia.) Therefore, the Hikayat is extant in most parts of South-East Asia.

The Hikayat Seri Rama (HSR) follows the Valmikian main frame but it is full of non-Valmiki motifs the origin of many of which can be traced back to Indian non-Valmiki stories. It also includes stories which are purely of local origin. Therefore, the large number of stories narrated in the HSR can be divided into three genres, namely, Valmiki, Indian non-Valmiki and HSR originals. It will be pertinent to discuss some of them.

The first four chapters have nothing to do with the Valmiki Ramayana. These are of local origin including the story of the birth of Rawana and his siblings, their marriage and children, young Rawana’s banishment for misbehaviour to Serandib Hill (Sri Lanka), his intense ascesis for twelve years and the boon of Allah through Nabi Adam granting him suzerainty over earth, heaven, sea and the netherworlds. However, Adam imposed one condition on Rawana, ‘…whenever you do something wrong or when your subjects do something wrong…and you do not judge them according to the way required by law, then everything, you too, will be destroyed by Allah Ta’alah.”

Rawana (HSR spelling) marries Nila Utama in heaven and begets a very tall and handsome son, named Inderajit who, when angry, grows three heads and six arms; in the Netherworld, he marries Pertiwi Devi and begets a son named Patala Maharayana; in the Sea, he marries Gangga Maha Dewi and begets a son named Gangga Mahasura. He then establishes a beautiful ‘state’ around Serandib Hill from where he rules “justly and compassionately.” Four states are not under his rule, - Indera Puri, Biru Harsha Purwa, Lekor Katakina and Aspaha Boga. There is a great battle between Raja Shaksha of Indera Puri and Balikasha of Biru Harsha Purwa. They are Rawana’s relatives. So, Rawana plays the role of a peacemaker successfully. This is a South-East Asian story and quite unrelated to the Ramayana, though at a later stage there is a rather weak attempt to establish some kind of relationship.

The main story begins from Chapter 5. As noted earlier, the HSR follows the Valmikian main frame but while travelling through time and space, a lot of confusion involving the characters and incidents enters the narrative creating a singular admixture of Valmiki, non-Valmiki and South-Asian stories. All the characters and incidents/episodes, though interesting, appear to be somewhat confusing and occasionally bereft of logic. A story begins with Valmiki but he is soon pushed aside and HSR takes over. Dasarata still is Rama’s father but he is also the great grandson of Prophet Adam himself. He builds his capital, Mandu Puri Nagara (Ayodhya?) and marries the exquisitely pretty Mandu-Dari, MahaBisnu’s daughter, whom he finds in a bamboo bush while building his capital. The royal couple is saved by a concubine, named, Bali-dari (Kaikeyi), from a fatal accident. Bali-dari also cures Dasarata of a painful boil by sucking out pus from it. So, Dasarata promises to make her son, begotten by him later, the king. On consuming four sanctified pomegranate seeds given by Maharishi Dewata, Mandu-dari gives birth to Seri Rama and Laksamana and Bali-dari, to Bardan (Bharata) and Chatardan (Shatrughna). Seri Rama being very naughty Mandu-dari suggests that Bardan should be the king as Rama is not fit to be a king. Dasarata agrees, recalling his earlier promise. One would notice that there is no question of the dramatic blackmail perpetrated by Manthara and Kaikeyi.

At this stage Rawana enters Dasarata’s story. Having heard of the beauty of Mandu-dari, he comes to Dasarata and demands Mandu-dari. Dasarata agrees and orders Mandu-dari to go with Rawana. Women appear to be nothing more than chattel in the world of HSR. Mandu-dari produces a green frog from the dirt (daki) of her body and, casting a spell, turns it into an exact replica of herself. The clone is known henceforth as Mandu-daki. The story of the frog turning into Mandu-daki is a tale also prevalent in the Oriya Ramayana. Rawana, ignorant of the replacement, departs happily. On the way back, he insults Maharishi Kasubarasa, ‘Are you a man or a monkey?’ Kasabarasa curses him, ‘You will die at the hands of men and monkeys.’

Dasarata, as soon as he discovers the secret, departs forthwith for Langkapuri, disguised first as a bird, and then as a little boy, meets Mandu-daki in secret, impregnates her by making love twice at night and happily returns to his capital. Rawana, unaware of all this, celebrates his marriage with Mandu-daki. In time, Mandu-daki gives birth to a daughter.

Therefore, in Dasarata’s story, Valmiki’s presence is marginal. From him only King Dasarata and his four sons have been taken merely to establish Rama’s background. The rest of the story is purely South-East Asian invention. Rama here has no divine connection perhaps keeping in mind the Islamic traditions – he is not an incarnation of ‘Wishnu’ but an ordinary man. However, he has been provided with a great ancestry – MahaBisnu on one side and prophet Adam on the other, a superb convergence of Islam and Hinduism!

Let us consider the story of Sita. She is born to Rawana and Mandu-daki. No one knows that she is actually Dasarata’s daughter. Rawana’s brother, Bibasenam (Bibhishana), a famous astrologer, predicts that Rawana’s life and death would depend on her. Rawana decides to kill her but on Mandu-daki’s prayer he places her in an iron box and throws the box in the sea. Mandu-daki wraps her in a chindai cloth and places two valuable jewels with her. ‘By the will of Allah-Ta’ala’ the iron box reaches Maharishi Kala (Janaka), king of Darwata Purwa. He and his wife, Queen Minuram Dewi (Sunayana of Valmiki), are pleased to have her and name her Sita. Here we are on familiar ground. Even though Valmiki does not tell this story, it is present in many non-Valmiki versions in India. In Valmiki’s Uttarakanda, we come across the story of Vedavati. While she is engaged in ascesis, Ravana attempts to molest her. She gives up her life in fire promising to be born again and be the cause of Ravana’s death. She is reborn as Sita. In Vasudevahindi of Sanghadasa, a Jaina Ramayana, Sita is Ravana’s daughter. It is predicted that she would be the cause of Ravana’s destruction and, therefore, she is put in a jewel box and abandoned in Janaka’s field. In Adbhut Ramayana too a similar story is narrated. In Dasaratha Jataka, a Buddhist tale of Rama, Dasharatha’s first wife has three issues, Rama, Lakshmana and Sita. After the death of his first wife, he marries again and has Bharata. When Rama and Lakshmana go to the forest, Sita accompanies her brothers. On return from the forest, she becomes the queen. In the conclusion it is said that in a previous birth Buddha was Rama and Yashodhara, Sita. It appears that marrying a sister does not invite any social stigma. In HSR too we see the same thing happening. In Gunabhadra’s Uttara Purana, Ravana disturbs the ascesis of Manivati of Alkapuri. She pledges to take revenge on Ravana. She is reborn as the daughter of Ravana and Mandodari. Here too the astrologers predict that she will be the cause of Ravana’s ruin. So, she is placed in a casket and buried in the ground of Mithila. Farmers discover her and Janaka adopts her. Jaimini in Sahasramukharavanacharitam knits a long story, taking elements from all Sita legends. She has three births. The first one is Vedavati who immolates herself in fire. She is then “born from sea-water on a lotus in form like Sree.” This inspires Ravisena to name her Padmaja, the one born on a lotus, in his Padmacarita, a Jain Ramayana. Ravana, found her and struck by lust, took her along with the lotus. A skyey voice warns him, “For lust do not touch her. She is your death.” Ravana throws her into the sea. Borne by the waves, she reaches the sacrificial grounds of Janaka. While ploughing the field, Janaka finds her. Happily, he adopts her and names her Sita. HSR incorporates all these stories and produces the story of Sita’s birth.

Time passes. Kala decides to get her married. Princes from everywhere gather except the sons of Dasarata. So, Kala goes to invite them. Rama and Laksamana accompany him. Here, the HSR spins a marvellous tale. There are four roads going to Kala’s kingdom. The forty-day road has no danger. The other three, taking 17, 20 and 30 days respectively, have three monsters, a terrible rakshasi named Jenkin, a gigantic rhino named Gigando and an enormous python named Suli Nagina. Rama chooses the 17-day road first, slays Jenkin and then travels through the other two roads too and kills Gigando and Suli Nagina, establishing his prowess in the eyes of Kala. This Jenkin story is possibly inspired by the slaying of Tadaka. The rest is entirely a South-East Asian creation. At least, I have not come across any such Indian tradition. The author of HSR has thrown in the rhino and the python for good measure in addition to the rakshasi.

Kala offers a challenge for the princes: he who can shoot an arrow through the seven palm trees (those he had planted when Sita was found and adopted), a parallel to Valmiki’s Haradhanu, gets to marry Sita. All the princes fail the test. Rama succeeds and qualifies to marry Sita. All are happy except four princes who plan to intercept Rama on his return journey.

Before the marriage, Rama has to solve a long-standing problem. A demonic crow named Gagak Sura has to be prevented from defecating in the two ponds containing milk and honey, thereby spoiling Kala’s rituals. Rama subdues Gagak Sura and extracts a promise from him that he will not spoil Kala’s rituals henceforth. This story has shades of Rama’s subduing of the rakshasas at the ritual grounds of Vishvamitra at Siddhashram. Rama is now ready to marry Sita.

But there is a further complication of South-East Asian origin. Kala, reluctant to lose his daughter, hides her among the statues in a temple. Rama displays his ingenuity in finding her by making her blink. This is again a product of the HSR creativity. Three brothers of Rama, however, do not get married here.

After the marriage, Rama does not go back to his father but decides to go to the forest directly since the kingdom had already been pledged to Bardan. So, Rama, Sita and Laksamana enter the forest, “with all followers”. In HSR, he has a large entourage. Here, we hear the curious story of Hanuman’s birth. At Maharishi Astana’s hermitage, Astana warns Laksamana about the existence of two enchanted ponds in the forest, one containing clear water and the other, muddy water. If one bathes in the pond with clear water, he will become an animal. The muddy water is safe. If turned into an animal, bathing in it will return one to his original form. While travelling, before Laksamana can warn Rama and Sita, they jump into the pond of clear water. They become monkeys, quickly get out of the water, climb a nearby tree, feel sexually aroused and make love, with Laksamana watching helplessly. He then forces the monkey couple out of the tree and throws them into the muddy water. They regain their human form. Laksamana is worried – will the baby be a monkey? The nursemaid, Baya Bata, is summoned and she makes Sita spew out a jewel. Rama dispatches Baya Bata to put the jewel in Anjati Dewi’s (Anjana) mouth who is performing ascesis with open mouth. Baya Bata does so and Anjati Dewi conceives. Hanuman is born with a human face with earrings and the body of a monkey. Here the name Baya Bata seems to be significant. It may be a replacement of Vayu. In Islamic traditions, gods of different denominations are not permitted. So, Vayu is replaced by Baya Bata – the name resembles the names of the Wind god, Vayu and Vata, - and she travels with the speed of Vayu.

The three settle down in Kasta Kastalanam forest on the banks of River Nadamna (Panchavati on the banks of Godavari in Valmiki). Here Rama slays a rakshasa who has no head and no arms and has his mouth in his belly. (Valmiki’s Kabandha, though the placement of the story is premature in HSR). The Surpanakha story is quite different in HSR though we find shades of Valmiki at places. For instance, Sura Pandaki’s (Surpanakha) husband, Barga Singa (Vidyutjihva) is killed accidentally. Her son too is killed by chance by Laksamana. So, she goes to their place of residence to take revenge but changes her mind and tries to seduce Rama and Laksamana. Having failed, she grabs Laksamana and rises to the sky. He cuts off her nose. She returns and Rawana promises to avenge her insult. So, he goes with two rakshasas, Teki and Martanja, who look like dogs, to Kasta and turns them into golden and silver deer (Maricha in a double role). Sita wants them alive. Rama goes to catch them leaving Laksamana to protect Sita. Here Rawana, not Maricha, lets out the cry for help in Rama’s voice. Sita forces Laksamana to go to help Rama. Laksamana draws a line, the famous Lakshman-rekha, and goes. This Lakshman-rekha is not Valmiki’s creation. It is not clear who started this tradition but in most non-Valmiki Ramayanas, this story occupies a prominent and popular status. Its popularity is such that it has come to be used as a metaphor in Indian society. Krittibas includes it in his Bengali Ramayana. Ranganatha Ramayana in Telugu too mentions this. We find Lakshman-rekha in Anandaramayana too (Mayyaitaam dhanusho rekham kritaam…). Though Tulsidas does not speak about Lakshman-rekha in the Aranyakanda of his Ramcharitmanas, in his Lankakanda, Mandodari tells Ravana that his claim to valour is useless because he could not even cross a small line drawn by Rama’s younger brother (Ramanuj laghurekh khachaii/so’u nahi naghehu asi manusai). Rawana comes and Sita offers him flowers instead of alms. She is then persuaded to cross the line and Rawana abducts her. The housemaids inform Rama of the abduction when he returns.

Sita is wearing a pink dress and she drops pieces of that dress to guide Rama, instead of ornaments. In Valmiki, she is ‘peeta-kausheyavasana’ (wearing a yellow silk dress) and drops her gold-coloured ‘uttariya’ (scarf, stole) and ornaments when she sees five vanaras on a mountain-top.

A Garuda bird, Jentayu Kasubarasa (Jatayu), son of sage Kasubarasa who had cursed Rawana that he would be killed by men and monkeys, tries to stop Rawana but is mortally wounded in the ensuing battle. Rawana escapes with Sita on his aerial chariot. How he fixes his chariot, which Jentayu had broken, is not clear. Jentayu’s elder brother, Aran-Aran (Arun), is the charioteer of Moon. One notices that the relationships narrated by Valmiki are all mixed up in HSR. In Valmiki, Jatayu is Arun’s son and Arun is the elder brother of Garuda and the charioteer of Sun.

Rawana deposits Sita in the Lotus garden instead of Valmiki’s Ashokavana and places Seri Jati (Trijata), Bibesanam’s young daughter here as her guard and companion. In Valmiki and Krittibas, Trijata is an old raksasi and not related to Vibhishana. After Rawana shows Sita the heads of two gods, supposed to be the heads of Rama and Laksamana, Seri Jati goes, meets Rama, returns with Hanuman and reassures Sita. In Valmiki, Ravana shows only Rama’s false head and Sarama, Vibhishana’s wife and Sita’s guard and companion, reassures her and offers to go to meet Rama – she has special powers to move incognito. Sita refuses and sends her instead to spy on Ravana. How Seri Jati meets Rama and returns immediately ‘walking’ the entire distance even before the bridge is built, remains unexplained. There are lots of inconsistencies like this in the entire book.

Sita plays an important role in Rawana’s death. This too is a HSR original. She reveals to Hanuman how Rawana can be killed: there is a small head “as big as a candle-nut” behind his right ear. If that is hit he will become powerless and his heads and limbs will not re-grow. He will not die but he will not be able even to stand up. Secondly, there is a sword with Madu-daki. She prays before it when Rawana is in battle and it makes him very strong. That sword has to be removed. How does she know this? She has heard. Such an important secret appears to be common knowledge!

Sita’s fire ordeal at the end of the war, is a lesson in fairness in HSR - Rama himself sits with Sita on the pyre! Fortunately, the fire refuses even to touch them. Rama is happy. Though Sita escapes the fire ordeal, she cannot avoid her exile. A non-Valmiki story sends her on exile. Kikewi Dewi, Bibasenam’s younger sister, makes her draw a picture of Rawana on her fan. When Sita falls asleep, Kikewi Dewi places the picture on the sleeping Sita. Rama finds her in that position, accuses her of infidelity on being instigated by Kikewi Dewi and sends her on exile. The parallel in the Indian non-Valmiki tradition is found in Chandravati’s Bengali Ramayana in which Kakua Devi, Dasharatha’s daughter, plays this malevolent role.

Sita goes on exile but not to a forest. With four hundred attendants she goes to her father Maharishi Kala. In HSR, Kala, being a Maharishi himself, plays a dual role as Janaka and Valmiki. At Kala’s palace, she gives birth to one son, not two: Tabalawi (Lava). One day, Kala goes to a spring with Tabalawi to bathe and forgets about Tabalawi. When he finishes bathing and meditating, he does not find Tabalawi. So, he creates an exact replica of Tabalawi casting a spell on a bunch of reeds and goes home with the child. There he finds Tabalawi sitting with Sita. He narrates the tale to Sita. Sita accepts him as her son and he is named Gusi. The story of Valmiki creating the twins appeared for the first time most probably in a Tibetan version of the epic. The HSR story is perhaps inspired by Somdeva’s story of Rama’s Naramedh Yajna included in the Kathasaritsagara, in which Lava is born as a single child. Here Sita goes, alone, to take a bath in the river. Valmiki, not finding Lava in the hermitage and thinking that he is lost, creates a duplicate by means of kusha grass. Lava returns. Sita too comes back. From now on they are two. The new boy is named Kusha as he is created from kusha grass. The story of a single child is narrated in Anandaramayana too.

In the HSR Sita is provided with a happy ending. After her return from exile, she is not taken away by Madhavi, Mother Earth. Rama and Sita spend forty blissful years together in a hermitage cared for by their children, grandchildren and vassal kings.

Let us now examine Rama’s position. Rama in HSR goes to the forest with his newly wedded wife and Laksamana. On the way, he subdues the four princes, angry at Sita’s marriage with Rama, a fascinating story entirely of South-East Asian origin and unknown in India. Sita never gets to see her father-in-law’s home. Rama settles down on the banks of Nadamna River with his family and a large entourage. After the Sura Pandaki episode, Rawana kidnaps Sita and imprisons her in the lotus garden. Rama and Laksamana set out to find her.

Rama-Laksamana walk on following the pieces of pink rag. They meet the birds, the crane who gets a long neck by Rama’s grace, the mortally wounded Jentayu who describes his battle with Rawana and dies, the gentle rakshasa of the cave who describes him as a descendant of Maha Bisnu and finally find Sugriwa hiding in the tamarind tree because the large leaves became tiny as those are now – all these, except Jentayu, are South-East Asian originals.

The story of Bali-Sugreeva conflict is more or less similar to that of Valmiki with a few exceptions. HSR has combined Valmiki’s Mayavi rakshasa and the buffalo-demon, Dundubhi, into one gigantic buffalo named Raja Safi and has included a South-East Asian story describing the history of the Raja Safi. After Beliya Raja (Bali) slays Raja Safi and finds that Sugriwa has usurped his kingdom, he banishes Sugriwa who takes shelter in a tamarind tree the leaves of which used to be very large in those days. Rishyamuk of Valmiki and the connected story is absent.

The story of Rama’s display of prowess is more or less the same in both Valmiki and HSR, both Ramas throw the gigantic skeletal frames of the demons and both cut down seven trees with a single arrow except that instead of seven sal trees (Valmiki) HSR has seven jackfruit trees – most probably sal tree is not available in HSR country – which are standing on the back of a coiled snake that Rama straightens by ‘chasing’ it.

In the ensuing battle between Bali and Sugreeva, as a mark of identification, Sugreeva wears a garland of Gajapushpi creeper in Valmiki and Rama rubs some betel-nut oil on Sugriwa’s back in HSR. Bali’s slaying is also somewhat different in HSR – Rama does shoot an arrow from hiding but Beliya Raja catches it. So, Rama has to reveal himself. He asks Beliya Raja to return the arrow but Beliya Raja refuses saying that this is the great arrow of MahaBisnu and if he lets go of it, it will surely kill him. Finally, he has to release it from his grip and it shoots up and slays him.

In HSR, Dasarata dies at this stage. Bardan and Chatardan come to Lekor Katakina (Kishkindhya) to request Rama to take over the kingdom. But Rama refuses and sends them back with his sandals and some good advice on administration. Compared to Valmiki, the positioning of the story is late but the description is similar.

Sugriwa is now ready to help Rama to find Sita. It will take a three -month jump to reach Langkapuri. None but Hanuman can do it. Rama recognises him, a tiny monkey covered in excreta, as his son by the ear ornament. He agrees to jump but he must be allowed to eat from the same leaf with Rama – this appears to be a South-East Asian custom making way into the story. Rama agrees but Hanuman must bathe in the sea before that. After all this is done, he is ready to jump. But he cannot, as everything, a tree, a stone, even earth, disappears from under his feet as he tries to jump. So, Rama asks him to jump from his arm, which he does. He reaches the house of the Maharishi Kipabara who possesses magical powers, meets the women of Langkapuri, goes with them carrying a water-pot in the guise of a Brahmin, places Rama’s ring in the water-pot and reaches Sita. Sita recognises the ring and converses affectionately with Hanuman. Then he proceeds to destroy Rawana’s mango tree and turns it upside down. The rakshasas capture him and take him to Rawana. On Hanuman’s own suggestion, he is wrapped in cloth and put on fire. He then burns Lankapuri and returns to Sita. She advises him to go to Mount Serandib and pay his respects to the black rock where Prophet Adam had come down from heaven. Hanuman does that and, jumping from the rock, returns to Rama. Except for the part in which Hanuman jumps to Lanka, meets Sita, shows her Rama’s ring and burns Langkapuri, the rest of the story is a South-East Asian invention. It is neither found in Valmiki nor in any other Indian tradition.

This story is followed by another curious story of the Maharishi Mahaganta who is not a human but a stick created by Betara Indera (Indra) to protect the celestial garden and lake on Mount Aruda from where the bridge to Langkapuri is to be built. But there is a problem. A rakshasa king, Jaya Sang and his son harass him and loot the garden continually. So, Rama sends his monkey army to subdue Maharaja Jaya Sang. They wage a long battle against Jaya Sang and his associates of three kingdoms and subdue them. Rama then gets the two pretty rakshasa princesses married to the two sons of Beliya Raja. This story is also an instance of South-East Asian creativity.

The story of subduing the sea follows it, which this time is inspired by Valmiki. When the bridge kept sinking in the sea, Rama got angry and wanted to dry up the sea. A beautiful woman, an emissary of Allah, appears and prevents him informing him of the existence of the fountain of the water of life at the bottom of the sea, which is the cause of his bridge sinking. Rama prays to Allah and the bridge floats up. Rawana tries again by sending his son, Gangga Mahasura, ruler of the water-world, to prevent the construction of the bridge. He and his army of fish try their best but the monkeys take care of them and have a sumptuous meal of fish and a giant crab. In Valmiki, the story is not so colourful. There, an angry Rama simply disciplines Varuna and he promises to remain quiet when the monkeys build the bridge.

Rawana then sends Saga Dasana, disguised as a monkey, to spy on the monkey army. Hanuman catches him and the monkeys rag him brutally. Rama has pity on him and lets him go. He reports back to Rawana and his description of the tails of the monkeys, all studded with various kinds of jewels and covered with gold, silver and marble, and an exaggerated narration of their prowess, is quite funny. This is similar to the Valmiki’s story of Suka, sans the HSR embellishments, followed by Suka and Sarana’s embassy. Suka and Sarana, however, do not face the misfortunes endured by Suka/Saga Dasana.

Rama reaches Langkapuri. Bibasenam joins him with his wife, Santaka Dewi (Sarama) and two sons. (In Chapter 2, Bibesanam’s wife is Marchu Dewi.) In Valmiki, Vibhishana joins Rama before Rama crosses the bridge, not after, and Sarama remains at Lanka as companion/guard of Sita, a role assigned to Trijata/Seri Jati, daughter of Bibasenam in HSR. War breaks out. Rawana’s troops are badly mauled. Rawana wakes up Kambakarna (Kumbhakarna). He fights for three days as against Valmiki’s one day. Then Rama slays him with just one arrow, a kind act as against Valmiki’s rather cruel killing of Kumbhakarna.

Rama then makes an attempt to establish peace. He sends a letter to Rawana suggesting a cessation of hostilities if Rawana returns Sita. Hanuman takes the message to Rawana’s court and delivers the message sitting on his coiled tail. This story of the coiled tail is not there in Valmiki but is available in Krittibas’ Bengali Ramayana though there it is Angada, not Hanuman, who sits on the coiled tail. The story must have been popular, especially in South India at the time since we find the image of a monkey sitting on his coiled tail in the sculptures of Pattadakal and Punjai temples. The story must have travelled to South-East Asia from these sources.

Badayasa, Rawana’s son, has a special power. If he looks at anyone, he turns into dust. That is why he is confined in a room, deep into earth, with a golden cover on his eyes. Rawana brings him out and sends him to destroy Rama by turning him into dust. Rama, forewarned by Bibasenam, creates a large mirror and places it in front of himself. Badayasa removes his eye-cover, looks at the mirror and destroys himself. This story is inspired by the story of Bhasmaksha/Bhashmalochana, narrated by Krittibas in his Bengali Ramayana, in which the demon burns himself to ashes by looking at the array of mirrors created by Rama with his Brahmastra.

The HSR resorts even to the Srimadbhagavat Geeta occasionally. One monkey tells a demon, “How can you kill Seri Rama if arrows don’t pierce his skin, swords can’t cut him, fire can’t burn him, water can’t drown him, poison can’t affect him?”

The story of Patala Maharayana, another son of Rawana, more or less follows Jaimini’s Mairavanacharitam, with minor differences. The story does not occur in Valmiki. In both the stories, Maharayana/Mairavana has magical powers, Hanuman protects Rama, Maharayana appears in various disguises to penetrate Hanuman’s defence and finally succeeds, takes Rama through a lotus-stalk to the netherworld, imprisons him in the temple of the goddess. Hanuman discovers the kidnapping, follows Rama through the lotus-stalk, reaches the netherworlds, defeats Maharayana’s Generals, meets Nerawati (Durdandi in Jaimini) whose son is in Maharayana’s prison, enters Maharayana’s city through the tricky balance-gate riding inside Nerawati’s pitcher, fights with Tamnat Gangga (King of Fishes in Jaimini, no name), the protector of the city, discovers that Tamnat is his own son, fights with Maharayana and his forces. Maharayana runs away. Hanuman makes Nerawati’s son king, picks up the sleeping Rama and returns through the lotus stalk. The main differences are: in Jaimini, Hanuman protects Rama by turning his tail into an impregnable rampart around Rama and Lakshmana, both Rama and Lakshmana are kidnapped and Mairavana is slain by Hanuman by destroying the seven bees who hold Mairavana’s life, whereas in HSR, Hanuman protects Rama by extending the hairs of his body, each hair long as Melima vine and sharp as a razor, Rama alone is kidnapped and Maharayana is not slain. However, Maharayana was slain on the battlefield the next day by Rama with a single arrow. Though I believe that Jaimini must be the source of the HSR story, I must mention that there is a plethora of literature on the Mairavana story in India. Any of these could have been used as the base. For example, Advaita’s Ramalingaamrita, Ramadasa’s Ananda Ramayana, etc. in Sanskrit, numerous tribal variations and many versions in vernacular, e.g., Mahiravanacharita in Telugu, Ram-katha in Assamese and most importantly, Krittibas’ Ramayana in Bengali, and some others.

The HSR long story of Inderajit, the three-headed handsome son of Rawana, is more or less a South-East Asian original with Valmiki and Vyasa peeping through it occasionally. He, being the king of Heaven, can do anything from the sky. So, he rains stones from the sky. Hanuman makes a fort with his tail of which the roof is provided by Garuda Mahavira. Garuda finds it difficult to hold the weight of the stones on his wings. Rama touches him and the stones slide off. Rama is injured by his poison arrow. Angkada brings the roots, leaves and bark of the tree planted by Nabi Adam on Adam’s Hill and Bibasenam saves Rama with these. Inderajit releases the Wimutasara arrow and puts everyone in the monkey camp to sleep, except Bibasenam. Inderajit enters surreptitiously and kills almost all. He is discovered by Bibasenam before he reaches Rama and runs away. We detect a whiff of Vyasa’s Ashvatthama in Sauptikaparva here. Rama sends Hanuman to Malaikiri (Malaygiri?) to bring the Vasliwayan (Vishalyakarani?) tree. Hanuman brings the entire mountain. All the dead monkeys come back to life. Hanuman takes the mountain back. We see Valmiki here again with slight modification. Hanuman then finds out about the special ritual Inderajit is about to perform. If he completes it successfully then all the dead relatives and warriors will regain life and all the enemies will lose. Laksamana and Hanuman go to Nikam Bali (Nikumbhila), the place of the ritual, with a large army and a great battle ensues. The ritual is incomplete. Inderajit rides a golden chariot and Laksamana rides Hanuman. Inderajit releases a special arrow, given to him by Adi Berma which will not hurt anyone if weapons are dropped. On the advice of Bibasenam, all drop their weapons. The deadly arrow does not find anyone to slay and lands on Rama’s neck as a garland – a story that combines two stories of Vyasa’s Mahabharata. After Drona is slain, Ashvatthama, out of desperate rage, releases the Narayana arrow. Krishna advises all to drop their weapons. The arrow is therefore thwarted. In another battle in the Dronaparva, Bhagadatta launches the terrible Vaishnava weapon at Arjuna. Krishna sees the danger and receives it on his own chest. The weapon becomes a garland on his neck. HSR has combined these two Mahabharata stories. Inderajit returns. Before he sets out for his final battle, the HSR describes a touching encounter between Inderajit and his wife, Kamala Dewi. It is narrated beautifully and is perhaps the best piece in the entire book. It reminds one of the parting encounter between Sudhanva and his wife before Sudhanva’s last battle in Jaimini’s Ashvamedhaparva. After a terrific battle between Laksamana and Inderajit, Rama, not Laksamana, slays Inderajit. Kamala Dewi joins her husband on the pyre. The story of Inderajit’s wife joining her husband’s body on the pyre, is not unique to HSR. Though Valmiki does not speak about it, it is available in many non-Valmiki traditions in India. The story appears for the first time in the Telugu Dvipada Ramayana where Sulochana, Inderajit’s wife, mounts her husband’s pyre and becomes a ‘suttee’. The story of Sulochana is also found in the Ananda Ramayana and Bhavartha Ramayana. We find this story in later works too, e.g., Jagatram’s Bengali Ramayana, Ramalingamrita, Maguni’s Oriya Ramayana, Rasamrita Ramayana, Rasikabihari’s Ramarasayana, Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s Meghnadbadh Kavya (the wife is named Pramila here) in Bengali, etc. Tulsidas also mentions Sulochana.

The story of Mula Matani, a fierce god with five hundred heads and a thousand arms, is an HSR original, not found anywhere in India. He is so big that “if he caught a fish in the river, he held it against the sun to cook it.” He and the seven god kings of the netherworld are asked by Rawana to fight for him. Mula Matani comes riding a huge chariot drawn by one lakh elephants (even lions draw chariots here). He wages a great battle but is finally slain by Rama.

Rawana, angry at Bibasenam for leaking all his secrets, now joins the war and launches a weapon named Widi, received from Berma Raja (Valmiki’s Shaktishel). Seeing it coming at Bibasenam, Laksamana rushes in and takes it on his chest. To save Laksamana, Hanuman is again dispatched to bring medicine. The weapon cannot be pulled out as it has grown roots and branches inside Laksamana’s body. Rawana sends a magician rakshasa to intercept Hanuman. Here the Krittibas story of Kalnemi-Gandhakali (crocodile/apsara) is deftly inserted by HSR. The rakshasa (Kalnemi) intercepts Hanuman and makes him drink water from the lake. The crocodile attacks Hanuman who kills it and releases the apsara (Gandhakali) from her curse. Interestingly, she becomes Hanuman’s lady love. In HSR, the rakshasa and the apsara are not named. He then kills the rakshasa, and not being able to identify the plants, returns with the entire mountain. But the medicine can be made only on the special mortar hidden under the bed of Rawana. Hanuman manages to penetrate the convoluted defence system of Rawana’s dragon bedroom and steals the mortar. Laksamana is saved. The mountain is thrown into the sea and the remaining medicine is used to revive all those who had died in the battle. The story is a nice mixture of HSR, Valmiki and Krittibas. We also see that Hanuman carries the medicine mountain twice, not once.

Then Rawana takes the field for the last time. He wages a great battle for four days. Rama could not overcome him. Hanuman then learns about Rawana’s vulnerability from Sita. Rama successfully uses the knowledge and Rawana falls, powerless. Rama stabs him repeatedly but he does not die. HSR does not mention Rawana’s death. It is presumed that he succumbs to his injuries later.

After Rawana’s fall, there is very little of Valmiki or any other Indian story in HSR except Chandravati’s Bengali story of Sita and Kakua Dewi. The last five chapters of HSR are entirely South-East Asian. Rama does not return to his own country but becomes the king of Langkapuri, not Bibasenam. Bardan, Chatardan and Maharishi Kala come to visit Rama and Sita. Kala, Bibasenam and Mandu-daki reveal the secret of Sita’s birth. Rama accepts Mandu-daki as his mother. Rama gets Bibasenam married to Bardan’s younger sister, Keluwi Dewi. Rama then founds a new city named Duria Puri Nagara on Mt. Maha Purita. Ramrajya, as described by Valmiki, is established in HSR too. Bibasenam is appointed as the Mangkubumi, Supreme Administrative officer.

Rama then sends Sita on exile due to the unfortunate misunderstanding engineered by Kikewi Dewi. She goes to her father and gives birth to Tabalawi (Lava). Kala creates Gusi (Kusha). They grow up to be brave and full of prowess. They kill many rakshasas. Rama realises his mistake and brings Sita back with her sons. Rama summons everyone including Bardan and Chatardan to his capital and launches himself into a spree of getting everyone married. Laksamana refuses, pledges never to get married and dedicates himself to a life-long service to Rama. Indera Kusuma Dewi, daughter of Inderajit, is brought from heaven and got married to Tabalawi. They are made king and queen of Duriya Puri Nagara, Rama’s new kingdom. Gangga Surani Dewi, daughter of Gangga Mahasura, king of the waterworld, is brought from under the sea and got married to Gusi. Later, Gusi becomes the king of Langkapuri. Bibasenam’s daughter, Dewi Sandari, is promised to Jama Menteri’s son, though she later gets married to Tabalawi. Bibasenam’s son gets married to Bardan’s daughter. Even Hanuman is asked to go and find his lady love, the apsara/crocodile (Gandhakali) which he does and has a nice time in the forest. Here HSR makes a feeble attempt to bring in a connection between the main story and the first four chapters – Rama asks Hanuman to settle down in Biru Harsha Purwa, the kingdom of Raja Balikasha whose story is described in the first four chapters. Rama also asks Bibasenam to be the king of Biru Harsha Purwa or Indera Puri Nagara, both of which were the kingdoms of Bibasenam’s grandfather. Bibasenam however prefers to stay on at Langkapuri. Rama then gets all his commanders married to the daughters of the rakshasa commanders. Finally, all the rakshasa widows are married to his army of monkeys.

An interesting story of Hanuman’s sexual misadventure is narrated at the end of the book. Hanuman is not the saintly ascetic we know him to be. Not only does he romp around in the forest with his lady love, the apsara, he also has glad eyes for Tabalawi’s lovely wife, Sandari Dewi. One day Hanuman escorts her home and seeing her exquisite beauty, falls for her, head over heels. He changes shape as Tabalawi and makes love to her. Tabalawi discovers this and challenges Hanuman. They fight and Gusi joins his brother. Hanuman is powerless against the brothers. Rama intervenes and stops the fight, but Tabalawi nurtures a lasting grudge against Hanuman. This story too appears to be of South-East Asian origin, possibly drawing inspiration from the fight between the twins and Hanuman during Rama’s Ashvamedha sacrifice described by Jaimini and Krittivas.

Rama builds a small hermitage at Andia Puri which the translator indicates to be Ayodhya in brackets. The reason for identifying Andia Puri with Ayodhya is not very clear. Rama spends the last forty years of his life peacefully with Sita, Laksamana and Hanuman, visited regularly by his sons, grandchildren and vassal kings.

This then is the Hikayat Seri Rama, the Malayan version of the epic, covered in 287 pages. The grand scale of the Ramayana is naturally lost here, “But it represents the popular form of the Rama saga…” The content, as has been seen, has a lot of “Indonesian leveling” influenced by local sources which has caused a large amount of intrusion of non-Indian motifs.

Harry Aveling, a much awarded and highly felicitated scholar, who received in 1991 the coveted Anugerah Pengembangan Sastera for his “commitment to the international understanding of Malay literature,” has translated directly from the Malayan manuscript held in the Bodelian Library. Most importantly, this is the first ever translation into English of the Hikayat Seri Rama. For that, the world readership will certainly be grateful to Aveling. It is a straight translation without any footnote or any explanatory note of any kind. The only explanations are provided in the Introduction and a select list of main characters. Some footnotes explaining the Malayan words, e,g., Betara, bezoar stone, lontar palm, chindai, penyuru, khalambak, birah, maja, etc, would have been useful. For instance, the word Betara stands for ‘god’ in Javanese, derived from the Sanskrit word, Bhattaraka. It would have been interesting to know that even an Islamic rendition of the epic does not refuse to recognise the use of a word referring to a Hindu god (Betara Indera) when it declares clearly at the very beginning that “I shall delete anything that is bad…” The language is smooth, creating a fitting ambience for such a book. In the Rama Katha of C. Bulcke, there is reference to a book entitled, Hikayet Maharaj Ravan. If Harry Aveling considers translating that too, it can be a good complement to his Hikayat Seri Rama and enrich the readership further.

There are many inconsistencies in the text. The numbers become confusing. Three lakhs become thirty lakhs in the following page, characters change their sex suddenly, distances increase or decrease according to the convenience of the story, etc. But these do not really disturb the reader. Those slips are natural in oral transmissions and multiple copying.

Similes and hyperboles, commonly used in mythological stories, like, blood flowed like a river, arrows fell like rain, ten lakh rakshasas, one lakh elephants drawing the chariot, etc. are used abundantly. But one simile appears to be quite unusual, “The weeping was unending like waves crashing on the shores of the Red Sea in Palestine.” I wonder where this comes from in the Ramayana! It must have been inspired by the author’s visit to those shores with the traders. There are some other interesting similes like, “arrow as big as a burning shrine,” “white rock as white as a newly-washed piece of cloth,” etc.

Writers Workshop has done an excellent job in producing this volume. It is obvious that a lot of care has been devoted to editing and proof-reading. Sturdily bound, well-printed, without noticeable printers’ devils, the book is worth possessing.

Images of artists performing Ramayana in Indonesia (c) istock.com

05-Jun-2021

More by : Maj. Gen. Shekhar Sen