Nov 03, 2025

Nov 03, 2025

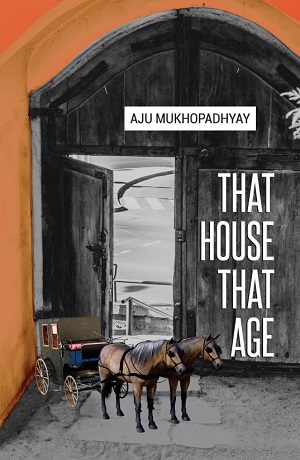

That House That Age – Chapter 14

L arge numbers of deaths occurred of known and unknown persons in his circle in his lifetime. He witnessed many cremations of bodies done as per the age-old beliefs and customs. Burning the bodies of the ones who lived in recent past creates long lasting grief. It creates a hiatus in our life, a gulf unbridgeable, as it seems. It is known that ultimately time consoles us, drying the tears from our eyes, healing the wounds in our hearts and rejuvenating our bodies. It helps us to forget the loss of our near and dear ones.

arge numbers of deaths occurred of known and unknown persons in his circle in his lifetime. He witnessed many cremations of bodies done as per the age-old beliefs and customs. Burning the bodies of the ones who lived in recent past creates long lasting grief. It creates a hiatus in our life, a gulf unbridgeable, as it seems. It is known that ultimately time consoles us, drying the tears from our eyes, healing the wounds in our hearts and rejuvenating our bodies. It helps us to forget the loss of our near and dear ones.

In his advanced age Rano was informed over the mobile phone that one of his cousin brothers-in-law suddenly died. They lived quite at a distance from their residence. Many in his position would not but he preferred to go lamenting the untimely loss to his cousin sister as the dead was married to her at his instance and he negotiated and made most of the arrangements for their marriage. For this particularly he felt an urge to go and meet the bereaved family. By the time he reached their home it was late in the evening. All were sitting in a grief-stricken circle listening to his nephew who was the only son of the dead. He had not seen them for long. They were out of sight out of mind, as it often happens in our life. However, he remembered the marriage of his sister and how

he took an energetic part in it. The dead brother-in-law was quite younger to him. He felt very sad.

The nephew who lived with his parents in the same house was telling that his mother had informed him of his father’s sudden death when he was very busy with business contacts and could not readily respond. After some time, he rang up to know the fact but said that he was too busy to come anon. He came in the afternoon when all ritual arrangements were already made, and they were waiting for him. Even without seeing the dead body he immediately left for the MLA’s home for he knew that crematoriums often remained crowded. He knew that such dignitaries have quotas for everything, getting preference over the others. Not that their family members died more often than the ordinary people, but the quotas were the symbols of their status; power to wield to keep the followers ever bowed and bound to them in their constituencies; a democratic power over the plebeians; weapons of a leader over the commoners.

However, as he knew him personally, my nephew could immediately manage to get the preferential order of burning his father out of the MLA’s quota. So only could he manage to get the work done by late evening. The funeral party had come back a little before Ranadeb visited them. The nephew was feeling a sense of success as he was narrating his part of the job. It seemed that he became successful in getting his dead father rid of the problem of waiting, maybe for the whole night. Even after death he would have to wait indefinitely but for his able son who relieved him of his pains of waiting. “Who knows?” The nephew said. His pride was tagged with this, “Who knows?”

Ranadeb did not know them intimately, especially after the marriage of his cousin sister who had lived together with him in the old joint family. He knew the brother-in-law as they were in a jovial family. His sister Minu and her husband Lalit used to sing even publicly in local functions. And he learnt that they taught their son too to sing and dance and he learnt that he had become a local celebrity even at his teens. Rano lived quite apart, and they met very occasionally. Now for the first time he saw his nephew closely. His sister had always spoken highly of her son at family gatherings. Ranadeb was wondering, when the son relieved all the pains and worries of his father after his death, how much he had relieved his pains and sorrows in the struggles of his life when he was alive!

While others were engaged in talks his mind went back to a forgotten village. Long back in his teens he went to a remote village with his father on the occasion of the death of one of their distant relatives. The dead was sort of a Zamindar of the village, a wealthy man with huge land holdings and some residential houses besides farmhouse, outhouse, garden house and others. He lived with numbers of relatives including his brothers’ families and their children and many dependents. He was a good-natured man who loved women too among others and married thrice as the first two were considered barren. But his third too could not gift him a child. No one verified if he was fit to create the gift. He was the Karta or head of the ancestral family. His own share of the property was the weightiest. He died at mature age but no one except perhaps his bosom friend, the city lawyer, knew to whom he bestowed most of his properties.

That was the first time that Rano accompanied the elders to such a place on such an occasion as his father did not object to his experiencing the burning of a body at night in a village burning ghat with a flowing river close by.

Someone in ochre dress coming out from the Kali Temple worshipped the dead and then all other rituals followed. Someone he doesn’t remember ignited the fire touching the mouth first, followed by others. In a half dark night with sickle moon overhead the shadowy gathering surrounding the burning body seemed ghostly. There were bushes and trees around.

At deep night when the sky seemed clearer, he saw some jackal like eyes burning in the bush. He distinctly remembered having seen eyes of the three wives of the late husband who had been sitting at the feet of the dead in the morning. They were as if observing what the men were doing with their dead. Occasional hooting of the owls, combined howling of the jackals at some distance, fireflies emitting lights and brighter stars scattered over the vast sky with the air around blowing haphazardly from the river side created an eerie ambience. The pyre was burning in fire licking the sky at its utmost height. Rano’s experience was exclusively his at that time.

Suddenly the three ladies who had been observing all that happened around the body vanished somewhere he could not follow with his eyes. By their eyes he recognised them. If they returned through the surrounding fields, they would be seen but they weren’t. All stood all along till the body was charred gradually. The billowing fire in the blowing air and the resulting smoke were reduced by stages.

The crowd was in its place till the burning was over. It was a hair-raising sensation to Rano. When asked, his father taking him aside said that it was impossible for ladies of that family to come out at night and observe the burning without permission. It was impossible! He smiled; “You have seen some others from the village,” he confirmed.

However, much Rano tried to convince himself that his observations were wrong he failed for the eyes never failed him, three eyes with different hues and shades had created an indelible impression in his mind when he saw them in the morning as well as at night. Was it a relationship between husband and wives that was beyond his comprehension? Were they apprehending that their widowhood would be ruinous? Were they guessing that they would get nothing out of the huge properties of the wealthy dead who was survived by the three miserable women! The most pernicious prospect of it was that none of them had any children.

Each burning is a history, each going into the grave is wrought by others unknown to the one who goes for burning or into the pit. How would he know how decorative or pompous way his, her burning or going into grave was! The dead isn’t responsible for any action at the state they attend. It is beyond his, her jurisdiction. any awareness beyond death is not an issue here. Whatever one does during his or her lifetime; for the others, for the country or for so many other entities, one maybe responsible too for one’s own life and actions but after death all responsibilities cease to exist. Putting into grave or burning a body or giving it to vultures to be eaten away is the responsibility of the living, not of the dead.

If Rano participated in talks or simply nodded, he didn’t remember but this he realized suddenly that the gathering in the room was thinned, and someone pointed out that it was eleven at night. After an hour another day would begin though it was night still. He would surely reach home but only on the next day.

The driver was sleeping in the car. He woke him up and they got ready for the journey when his nephew came out. Rano told him that he would have to do lots. Lots of works were to be done till the ceremony of the dead would be over including the feasting of relatives and others. He was replied that he would hardly get time for all work for which he would engage some friends and relatives who had already gathered hearing about the sickness of his father of which he wasn’t quite aware. His mother didn’t tell him. They were staying put for some days, they would be responsible for the rest of the work to be done. He continued to tell Rano that he would be awfully busy for some more days because it was the season of his business cycle that shapes the trend for the whole year. However, he promised to come to invite them. He seemed worried for possible loss of time which is more required for his business than for these funeral rituals. At last, Minu came out to bid him good night. Consoling her Rano waited for his car to start.

As the car ran through the less crowded road at night, the thought of cremation engaged all his attention touching him to the core bringing back to his memory the other near and dear ones who left the earth. Once again it dawned on him that the time for it in their lives might not be far away. He thought with some foreboding that in this busy nuclear age his own off springs living in distant countries would be more embarrassed than becoming grief stricken when that time would arrive though he had clear hope that it would be different for them as confirmed by the very active participation and presence of one of them in helping them to survive while in sickbed. All worries are up to their passing away; it would be beyond them to do anything more once that happens. Kind of grief, remorse and repentance began gnawing at his heart when it came to deaths of more near and dear ones like his parents.

His mother died when Rano was just eight years old. He remembers that she was in a secluded bed in a corner of the room. She was nursed by her sisters-in-law and others from time to time. For how long he did not remember. She was consumptive; frail and emaciated then. He learnt later that she had been suffering from tuberculosis. Doctors came from time to time, but he did not know what they said, what was discussed. Suddenly in the morning of a fated day he found her lying in her bed as usual but was shifted in the middle of the room surrounded by a gathering. She died at the very early age of 30 years. Her face was being cleaned and freshened with some unguents and spicy materials, maybe with something like sandalwood paste and vermilion paste as she was survived by her husband. She was garlanded. Though she did not look very nice she looked quite better compared to her look during the past few days.

There were adults and children around. Rano could not make out how it happened. Elders did not answer. As others, he too cried with his brothers and sisters, with all cousins who were allowed to remain there. His father was lamenting in deep sorrow. He remembers him uttering something like she looked as if she was getting married again. Once again, she looked like a bride. As the day wore on further arrangements were made towards the funeral and children with others not useful for anything then, were asked to go. They were consoled by the elders and separated from the mourning crowd.

Rano was not allowed to accompany her dead body to the crematorium. In those days incinerators were not introduced in the crematoriums. The traditional process of burning using big logs of wood was followed. Following the age-old tradition her body was carried in a cot held on the shoulders of four persons holding four legs of the cot, followed by others in the funeral procession which led to the Nimtola Smashan Ghat at the bank of Hooghly River, part of Ganges. It was the usual crematorium, for the dead in their locality, not far away from their home. Men accompanying the body came back in the evening. Elaborate rituals were followed which continued for about a fortnight.

Rano heard his father telling with remorse and frustration how his utmost efforts almost saved her but for a mistake in complying with the request of the kaviraj, the ayurvedic physician, all the fruits of his efforts for some days were ruined. He said then and many times thereafter to good number of their relatives and well-wishers how he was betrayed by himself. The story was that usual treatment could not cure her; the disease was taking toll rapidly on her body when he approached many for possible remedies and then what happened at last was the story of stories.

Hearing from someone that a saintly man, a Tantric worshipper of Goddess Kali, used to have trances from time to time. During his meditation he used to be guided directly by the Goddess when something unexpected might happen through him.

Rano’s father went to that man and requested for a cure as his mother was still young in age and was carrying big responsibility on her shoulder as Housewife-in-charge of the household, being the wife of the eldest son in the joint family. His father implored him on many days before the day he was granted time during his meditation to hear her case. He was present during the meditation session. After some time of his beginning to meditate invoking the power of the Goddess, the adept Tantric began sweating profusely when winter was approaching with some chill in the air. It was October. He started talking with someone. During this time his father was hearing him intently. The Tantric was heard imploring the one he was talking to, to give the remedy but he was being repeatedly told that the life span of the person involved was very limited, she was fated to leave her body soon and that nothing could be done. Very frustrated, the husband of the sick touched the feet of the Tantric and repeatedly implored to do something to save her. After some time, he again tried and this time he got a remedy. He prescribed the juice of the leaves of snake plant (Sansevieria Cylindrica) in particular dose but with a strict condition that he should not divulge the remedy to anybody. If he broke the vow of secrecy the remedy would not work. Usually, this plant was not used as medicine for any ailment, at least in their known circle. It is poisonous to some extent. But when this was tried on the sick it worked miraculously as she was visibly recovering, the husband asserted. That kaviraj was one of the physicians who had treated Rano’s mother for some time. He lived nearby and often met Rano’s father on his way. He would enquire casually as before about the progress of the treatment. Once he was replied, “Well, it is to our great fortune that she is recovering.” Then the physician requested him to tell who the doctor and what was the medicine given. Again and again, even coming to their home, the man persistently requested Rano’s father to tell him the medicine, saying that he would never tell it in his life to anybody else. The husband of the sick avoided him for sometimes but on his regular request once narrated half of the story, saying that he was under vow of secrecy never to tell the name of the remedy. By nature, Rano’s father was a simple man without the capacity to hide anything; he never was secretive. He passed through a hard time in keeping the secrecy. Finally, he could not keep his promise and one day disclosed everything to the physician who was very amicable, well known to his family, but knew how to get his work done for he might have thought that with this miraculous remedy he would cure many of his patients and would get adequate name and fame and consequently increased business.

The narrator felt duped but could not say anything to the Kaviraj because he knew that it was a play with himself; that it was a ploy by the unknown agent to make him break his promise as it was, to assure that fate would be fulfilled in death. Under repeated submission she was granted the boon to be taken back on its disclosure thereby proving the truth of fate. Fate of course, those who believe it believe that it works beyond reason. So, this was something great to learn how chance came to be lost; a providential judgment!

Rano’s father lived almost up to a century. From his childhood Rano lived with his father. He remembers his life when his mother was there; she was drowned in domestic works with little rest and entertainment and his father was never quite active. He relished his stay in bed, rather than busying for anything else. Sometimes he sat for a while talking to someone or the other. He had a good physique; a big belly and big chest, both measuring 48 inches while he said that his father had them measured up to 52 inches. While his weight was quarter to three maunds or about 105 kilograms his father’s weight was quarter to four maunds or 135 kilograms. Rano heard many times the feat of his father’s eating capacity as he said. He witnessed something of it in his childhood.

But some disease developed in his father Balaram Roy Chowdhury in advanced age like sort of bronchial problem causing hemorrhage from the throat. He had sort of confidence about the non-vulnerability of his body. After some weakness or defect in his chest was detected and he was taken to a hospital where he was asked by the specialist Doctor, what was his problem, to which he replied, “Nothing!” He was not examined further and was released at the onset. However, at the old age beyond 70 neither he could eat as before, nor he could manage to obtain as much food. His health was gradually broken down. Rano thinks that it was so because he did not work; no exercise, neither of body nor of mind except hearing the radio for some time and joking with the juniors from time to time. He had developed problems in his Hernia. Once after returning home Rano found that his father had been badly suffering from pain lying in bed and none present before him could find a clue, offer a remedy. Deciding to take him to the hospital in no time Rano, while getting ready, had a foreboding about the fate of his father. He immediately took him to a hospital where he was diagnosed having his Hernia strangulated for which they suggested immediate surgical operation as it was the only way

to save the patient. Doctors and Rano agreed, his father remaining neutral. But there was no time; it was to be performed immediately.

While he was taken in he was asked to leave his shoes outside. He hesitated first for even at home he used sandals and never walked with naked feet. He was proud of the soles of his feet which were reddish and as glazy as the face. He was over conscious of his body. When he was told that that was a must, he told Rano to keep the shoes properly and take them home later. That was done. When some other relatives came to see him, he complained that the doctor prohibited his taking water while he was thirsty. They had to keep mum. When Rano suggested something to the doctor he was asked, “Are you a doctor?” He said, “No”. Rano knew that a General Hospital was different from a Nursing Home where good amount of money was claimed from the beginning, but they behaved better. However, the ailing part of the body of the patient was operated upon successfully and he survived. Rano went to his bed to find that he was sleeping with oxygen tubes fitted to his noses.

At midnight they were informed by the hospital that the patient had expired. In the early morning they went to find his body sifted to morgue. It was a case of post operation cardiac arrest. None was there to explain it further as to how it could happen when the operation was successful, and the patient was resting. But it happens, normal in medical history, he was told. Formalities over, his body was taken out and carried to their rented residence. That old house was sold quite some time ago.

Rano was upset finding his father in the morgue sent so soon after his death. While trying to open the kurta from his body, usually mentioned as Punjabi in Bangla, he felt obstruction though none obstructed. Certainly, he was very agitated at the death of his father as it happened unexpectedly even as he had some foreboding. Mentally he was knocked down, psychologically upset. In fact, he was involved personally in it and intimately too as they were remaining then in separate rented shelter, none of his elders were there belonging to that house to guide and help him. He remained affected mentally for a long time with a kind of frustration and failure in running the affairs of the family. His father was there just to be carried in his old age, lazily lying down, an extension of his lifestyle. His presence in the new atmosphere was kind of bewilderment but Rano never wished anything like that to happen as happened at last. Sort of indecision he was involved in as if a novice who could not act properly and in time though many deaths he had seen before. It was a hesitation, a jolt received in the movement of life; a groping for something not yet within reach.

After some rituals, with the help from neighbors he carried the body to the crematorium, and it was assigned to fire after he touched the mouth with fire on a stalk as per their religious system. Then the paraphernalia followed as usual. It was a Holi festival or Dol day when all smeared others with colours in different ways; a festival of colours. His action with others of his group was in contrast to the festive mood of the day. But then, Rano considered later that that day comes in a mortal’s life once only after birth when he leaves the earth, on any day of the year; it did not matter even if it was a festival for others.

Rano felt mentally disturbed for something not exactly explainable at the death of his father. His father, towards the

last, did not possess many items for personal use or consumption. There weren’t many things preserved by him or kept for him except the very usual items like dresses. But he had a small metal hand box. No one knew when he handled it. It was found in a remote niche at the corner of the room after two, three days of his death when everything in the room was getting rearranged. When opened with some curiosity it was found that there were two, three notebooks with some jottings by him and some small items like butt of a pencil and an ink bottle, some coins, bundle of bidis coiled and bound by threads and two match boxes. There was a small chisel and a small hammer. It flashed in Rano’s mind that the chisel was sometimes used by his father to cut a portion from a gold bar to be sold to the goldsmith when he had deficiency of cash in hand. The most important thing Rano got from the box was a small, printed post card size white card, a record of his mother’s admission to the maternity home and her release after his birth. In a corner of the card his father noted the time and date of his birth with a pencil which was the correct record of his birth. A portion of the timeworn card was torn at the corner. Let that be so but it was the true record, Rano assured himself as during that time few insisted on birth certificates, and many were born at home without the help of any doctors or nurse. The wet nurse was enough. His date of birth as recorded in the school was based on verbal words of mouth by the guardian who took his ward for admission. There might be trifle reason for the difference between that recording and the actual record of birth; the guardian did not remember the exact date and year of birth. It was no part of essential statement then about the student getting admission.

He carried his simple life physically doing pretty little, thinking lesser; mostly reminiscing the existence and activities of his father, the happenings around them at that time and frustrating about the failure of living a life dreamt due to the untimely death of his father; telling and retelling the stories regurgitating from his memories throughout his remaining life to all old and new to the family, to all guests, family friends and others who might meet and stay for some time to help him relate them.

His grandfather’s death also was caused by operation on his body by an efficient European surgeon, as Rano heard. The operation was done while the patient was aware of it and it was said that he shouted in pain to such a volume and pitch of his voice that most in the vicinity, even in the spreading locality heard it. Rano was not involved in it in the least except feeling distress and pity for the patient gone by long ago. He could not do anything other than hearing it later.

His grandmother whom he saw in his childhood as a kindhearted aged woman, calling a crying child, taking it in her lap and giving something like sweetmeat or chocolate to eat. She loved all her grandchildren like her own children but loved the first granddaughter most who was very fond of her. She used to give her chewed pan (betel leaf and betel nut) to further chew. Both enjoyed it. She died of dropsy before Rano's mother, Rano was child aged less than eight at the time of his mother’s death. He faintly remembers his grandmother's body to be carried down rolled in mattresses and heavy cloth coverings; none could look at her body.

Rano was loved by her sometimes with extra affection as the child experienced. She loved his mother most as the wife of her first son and also as a very obedient housewife doing all odd jobs as required without a question. Rano heard that overruling the usual custom she went to the bride’s home where she was getting married with her first son at the dead of the night as it was the right time for their marriage according to the almanac. She went alone with the carriage driver without any prior arrangement or appointment. Usually, the mother of the bridegroom never accompanied the marriage party.

Rano remembers observing her when she used to water her plants kept in rows on the roof. No one else used to be near her at that time except Rano. She too knew it. She was Shodashibala Devi. Rano still keeps and maintains rows of plants on the roof, in the balcony and on the ground floor of the home he lives in. He was indirectly introduced to this love for the plants in his childhood by his grandmother as a booster towards his natural relationship of love for plants. He has been maintaining many flowering and leafy plants; varieties of cacti and other species of plants throughout his life. This he did even when he was posted at distant places; nurturing plants varying in quantity is a part of his lifestyle. Now his wife waters the plants to help him. Rano has ever been a virtual gardener indeed.

Rano witnessed his uncles’ death, even the death of some children as a member of the old household but he was not directly involved though once at the death of his youngest uncle in their changed house he became emotionally moved and cried aloud.

Ranadeb witnessed or became concerned with some deaths; sometimes participating in the funeral procession or taking parts in rituals but he was not involved personally on most occasions as there were many in that big family to take care of them. The subject of death took him to the sublime ideas about it, how it was understood or dealt in by some others, sometimes people of some extraordinary capacity. Sometimes Rano ruminates over some extraordinary deaths; either heard or read by him; the spot of death visited by him at one time or the other like an extraordinary man welcomed death and arranged for its visit. A divine personality denying death to take hold of her and fought vigorously but finally her body yielded to its pressure while she escaped to another plain of existence. Someone did not easily succumb to it. He fought valiantly with it, quite consciously and finally yielded to it and someone merged into it.

Death was not a surprise nor a wonder or occasion for fear or cowardice to them. Someone like Tagore really suffered actual death from the time he was ailing for the last time and was in his deathbed. But earlier he was romantic enough to call it a lover like Sri Radha to Krishna. Ranadeb always recapitulates some deaths extraordinary; the owners of the bodies did not easily accept death’s entrance but finally allowed without any remorse. He remembers them with utmost reverence. Some greater ones entered into death at will; they knew its time of coning and merged into it.

Pavhari Baba, an Indian saint and yogi, used to live in an underground cave dug and constructed by him near the river Ganga at Ghazipur. He lived by such trifles as leaves and chilies if someone gave him. He was called ‘air eater’. He silently did the Yoga without involving others. He self-immolated his body sensing the footsteps of death near him in 1898; that was his last oblation to the divine. Smelling burning flesh people went down to witness it, know the truth.

Mother of Sri Aurobindo Ashram felt alarmed at the approach of Death at her door for some months. She was spiritually transforming her body cells as her most important job at that time. Few days before her departure to the other world she challenged Death. She did not care for her failing heart, weak body succumbing to the pressure of various diseases dwelling in her, she didn’t care much about the death's alarm bells near her. Towards the end she asked her disciples to raise her head and body and help her walk. They did. Legs failing, she forced them to move while feeling the grip of death. Even half an hour before her death she asked them to lift her body. They complied. She and Death gripped each other. She, a spiritually conscious being, the Mother of Eternity, Mother of Love and Compassion, Mother the valiant fighter, sensed well the approach of Death at every moment; an obstruction to her most important work, the transformation of the body, and tried to defy it. Pain and fear were beyond her, but she realized that her body, part of the old creation, could not serve her more than 95 years this time. She had her second body prepared in the subtle world to give her shelter when she would finally leave her old abode. She left it in the evening on 17 November, 1973, at 7.26 pm, a year after the centenary of Sri Aurobindo’s birth, after celebrating it properly.

This body was earthly body unlike her body in the other world. She was earlier in other bodies that suited her work. From the beginning of the earth, whenever and wherever there was a spark of consciousness. She was there. She is; She will be with us even in her physical absence.

Soldiers may die any time in war. A simple soldier became great by defying death. He was Jaswant Singh Rawat, a

rifleman hailing from Uttarakhand. He was one of the three soldiers belonging to 4th Garhwal Rifles, given charge of Nuranang post in the Himalayas in Arunachal Pradesh during the Indo-China conflict in 1962. When the last two soldiers in his group died after fighting heroically, Jaswant alone clearing the obstruction created by the five sentries of the enemy soldiers, captured the machine gun (MMG) of the enemy which was firing on them continuously and accurately. He brought it home.

After the death of the last two Jaswant was ordered to retreat but he defied the order and continued to fight alone from three-gun points created by him, helped by two local girls, Sela and Nura, who with emotional and sympathetic attachment to him and out of patriotic zeal came forward voluntarily to help him though they weren’t soldiers. Jaswant fought alone against a battalion of enemy soldiers who came under the illusion that they faced a big Indian battalion; actually, headed and executed by one person. There were casualties of 300 soldiers, dead on the enemy side. The fight continued for three days. Jaswant alone fought from three points valiantly jumping from point to point, getting injured and losing one or two limbs; his other body parts eventually fought with the rest till the end. When the enemies could know the actual Indian position through the betrayal, maybe under compulsion, of a food supplier caught by them, Jaswant was alone. Facing the risk of being caught he committed suicide by shooting himself.

While he was court-martialed by the Indian Military for defying order, must be posthumously, the Chinese soldiers out of revenge chopped his head and took it to their side. Then after realizing his great courage and inhuman feat they returned the head with a brass bass in his honour. And Indian side later honoured their extraordinary soldier by keeping his room reserved under the supervision of soldiers and by providing him breakfast, lunch and dinner at the right times till the present day; changing his bed sheet and everything as if he lives. Government keeps him on the role and records as if he is in service, promoting him up to Major General, giving him leave and remitting his salary to his dependents.

Jaswant has become a legend in the Army, as if he really lives and guards Indian soldiers under all conditions. Jaswant Singh Rawat the legend lives still in all respects except his bodily presence. Eye witnessing soldiers say that his bed and other things seem to have been used during the night when seen in the next morning. He has become a Saint in the eyes of Indian soldiers and the monument erected in Arunachal Pradesh at the site he fought but not fell, is named “Jaswant Garh”. His Sainthood seems more natural than a decision by an institutional authority. Jaswant was and still is real. Rano visited Jaswant Garh.

Rano celebrates another valiant soldier; a great monk who won the world by his spiritual power, intellectual depth and the height of truth he represented. He was Swami Vivekananda. Saint Sri Ramakrishna predicted about his greatest disciple Swami Vivekananda who was nicknamed Naren, that when he would realise who he was actually, he would refuse to remain in body and that after the end of his work on earth in this life he would enter Nirvikalpa Samadhi. Sister Nivedita (Margaret Nobel), the prime disciple of Swami Vivekananda was once recalling an incident, “Not long before his departure some of his brother-monks were one day talking about the old days, and one of them asked him

quite casually ‘Do you know yet who you were, Swamiji?’ His unexpected reply, ‘Yes, I know now!’ awed them into silence, and none dared to question him further.”

One day Mrs. Macleod was in Swamiji’s room at Belur Math when the Swami said to her, “I shall never be forty.”

Knowing that he was 39 she said, “But Swami, Buddha did not do his great work until between forty and eighty.”

“But”, he said, “I have delivered my message and I must go.”

Three days before his passing away when the Swami was walking up and down on the spacious lawn of the monastery in the afternoon with Swami Premananda, he pointed to a particular spot on the bank of the Ganga, and said gravely to him, “When I give up the body cremate it there!”

On that very spot stands today a temple in his honour as his Samadhi.

Two days before his passing, on 2 July 1902 when Sister Nivedita visited the Math Swamiji insisted on serving her the lunch with boiled jackfruit seeds, boiled potatoes, boiled rice and ice-cold milk. When she finished, he poured water on her hands to wash and after that he himself dried them with a towel. At this the sister protested, “It is I who should do these things for you, Swamiji! Not you for me!” But his answer was startling in its solemnity: “Jesus washed the feet of his disciples!” to which Sister’s reply could not be uttered though it came to her lips, “But that was the last time!”

Then came the last day in his life. He rose up early and meditated for three long hours in the chapel of the monastery

closing all the windows and bolting all the doors. And at last broke into a beautiful song dedicated to the Goddess Kali. He was immersed in Vedeanta philosophy, worshiper of the One and One without a second as the absolute truth but as his Guru ever remained a Kali worshiper in spite of getting initiated in many religions, he too never opposed worshiping the idol of Gods and Goddesses. He introduced Durga Puja at Belur Math and now he proposed Kali Puja on the next day. Though it was not done then as he himself left the earth on that day. It was performed a month later and it is being done in all the years thereafter.

He had to say many more things on that day. He said that he would do something for Japan and that he would meet Ramesh Chandra Dutta, the great savant and historian, somewhere in the universe. He asked a disciple to fetch a book titled Shukla-Yajur-Veda, an ancient script. He pointed out that the fortieth verse in its eighteenth chapter referred to Sushumna nerve in the spinal cord of the body, a subtle passage through which Tantrics tell us that the Mother force or what is described by them as the serpent power, passes which usually sleeps coiled at the base of the spine. In the above Veda it referred to the Moon in the form of Gandharva which is Sushumna which gives supreme happiness, etc. Thus, Swamiji wished to mention that Veda was the original source of Tantra. The basic idea of Tantra, Sushumna, was mentioned in that Veda much before the advent of Tantra. There is a belief among some tantrics and other scholars that Tantra Shastra was older than Vedas. Swamiji asked his disciples to further study the subject with reference to that Veda to ascertain the truth. It is not known how far such studies were made and what result was obtained. However, it seems that Swami Vivekananda wished to point out in accordance with the common belief that Vedas were the source of the great religions that emerged later in the subcontinent which influenced Buddhism too as there was a distinct branch called Buddhist Tantra.

Many unusual things happened on that day. It was unusual for him to dine with other brother monks but on that day, he dined at the refectory with all of them and felt quite better praising the quality of foods and his satisfaction in taking them. After some forty-five minutes of the lunch, he entered the area of the Brahmacharins or the celibates and taught Sanskrit grammar for three hours making the heavy subject lighter spiced with jokes and remarks. And in the evening, he walked to a long distance up to the Bazar accompanied by Swami Premananda which too was not usual. It seemed that he wanted to do many things on that single day which he did from time to time on other days. He was soliloquizing while moving in the courtyard of the monastery that had there been another Vivekananda, he would have understood what Vivekananda had done! Swami Premananda who moved close to him overheard them.

In the evening when call was given for all to assemble for evening rituals, he retired in his room at 7 pm telling others that none was to disturb him until called by him. And again, the doors and windows were closed and he immersed in meditation. After an hour he lay down in his bed and called a disciple to massage his head. Someone was fanning him. He asked him not to fan but massage his feet. Thus, he remained for an hour, as if meditating or sleeping. And then his hands trembled a little, body was slightly shaken, and he released a deep breath. After a minute or so he again deep breathed and then lay motionless. It seemed that he was gone. His eyes were fixed in the middle of his eyebrows and in the morning, it was found that his eyes were bloodshot; slight blood oozed out from his mouth and nostrils. Doctors could not find the real cause of his death other than making some guesses with plausible remarks. Monks thought that due to intense japa and meditation the aperture at the crown of his head, the Brahmarandhra was pierced; he breathed his last while in Samadhi as it was predicted by his master. By all circumstantial evidence it seemed that he died at his Will at the age of thirty-nine years, five months and twenty-four days; much earlier than forty.

Continued to Next Page

06-Nov-2021

More by : Aju Mukhopadhyay