Feb 16, 2026

Feb 16, 2026

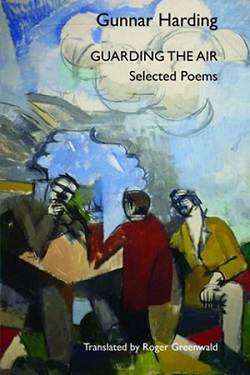

Guarding The Air: Selected Poems of Gunnar Harding

translated and edited by Roger Greenwald (Black Widow Press, 2014).

321 pages. ISBN 978-0-9856122-7-6. US $24

To arrive at nothing is no reason for disappointment

if arriving at something was never one’s purpose.

(from “The Star-diver”)

While many poetry readers are familiar with the Swedish Poet Tomas Tranströmer, the 2012 Nobel Laureate for literature, they may not know that Sweden harbors other great poets. Guarding the Air pays wonderful homage to one of them, Gunnar Harding, by presenting work that spans a lifetime of poetry.

For nearly half a century, as a poet, writer, translator, editor and literary critic, Gunnar Harding has been at the center of Swedish literary life. He started as a jazz musician, studied painting in Stockholm, and made his literary debut in 1967. He has published eighteen volumes of poetry, as well as translations and nonfiction, and has won many prestigious literary awards in Sweden, including the Dobloug Prize from the Swedish Academy.

Guarding the Air is the first comprehensive selection of Harding’s work drawn from most of his volumes of poetry written in verse (prose poems are not included). It begins with a crisp but essential introduction by the translator and editor, Roger Greenwald, an American poet who is well known for his translations of Scandinavian poetry. (His selections of work by such poets as Norway’s Rolf Jacobsen and Tarjei Vesaas have won him many translation awards.) He has also done readers a service by translating Gunnar Harding’s prefaces to three of his Swedish volumes of selected poems. The book also features line drawings by the poet that lend it a special charm.

Harding’s interest in poetry and culture spans many continents and cultures, and he is candid in listing his inspirational sources. In a preface to one of his volumes of selected poems, Wherever the Wind Is Blowing, he refers to the English orator Edward Young’s saying that “we are born originals but we die as copies.” But Harding argues that in “conversation” with others, we gradually become original. His evolution as a poet bears witness to that process. Art, freedom, love, memory and shared experiences, the passage of time, sensuality, and mortality are some of the many themes that get beautifully woven into the rich tapestries of Harding’s poems. The diversity of the subject matter helps to make this collection resonate, whether in a poem about a wandering shoemaker or in poems exploring music and art. And Greenwald has done a magical job in capturing the intensity and depth of feeling in the poetry.

Life pulsating in many corners forms an integral part of Harding’s poetry. His poems achieve a fine balance of emotional and philosophical content. One can never underestimate his capacity for tenderness, as in the first poem in this collection, “Northwest Express,” which starts with these lovely lines:

For Harding, feelings are important in poetry. He articulates this in a preface: “I know it sounds sentimental, but I believe it is important to keep faith in this truth of the imagination. Moreover — even though it sounds still more sentimental — I believe that it is important to insist that the feelings that come from the heart are sacred. If they are missing, then we are facing a devaluation not only of truth and beauty, but also of poetry.”

Although love is the best balm for man’s soul, the poet knows the absurdity and misery of loving everyone, as finely evoked in these lines:

The poet is also aware of the ambivalence that hides behind love:

Obstacles to experiencing the true feel of changes in the beautiful outer world also command the poet’s attention. The poem “Ich Weiss nicht, was soll es bedeuten” (whose title is from the opening lines of Heinrich Heine’s “Die Lorelei”: “I do not know what it might mean / that I am so sad”) starts with a question that arises from Heine’s and then moves on to the predicament of our consciousness amidst mechanized urban life. The last line in the poem’s final stanza has a certain poignancy.

Memory and the associated feelings surface in many poems. In the fascinating poem “Puberty,” the speaker conjures up his school years, a whole class that has been submerged in his memory just as it once was submerged in the green water of a chlorinated swimming pool. The poem ends with an image of a boy (no doubt the poet himself) diving into those waters/memories — and being brought up short by the passage of time:

In “Persephone,” the poet comes up with a striking simile: “He will carry her like eczema in his memory.” Again, in “Triptych for Nils Kölare,” the poet notes:

As the image of white hair reminds us, the longer our memories are, the closer thoughts of mortality come. Even Harding’s early poems are mindful of this. “September,” for example, is set against the backdrop of the war in Vietnam. A frayed poster says “USA OUT OF INDOCHINA,” and the poet observes: “Many / have died so that you might be born, this / unites you with those / who are dying right now.” The poem proceeds to this moving passage.

But the poem concludes with a touch of surprising, if somewhat grim, humor:

In a later poem, “The National Hospital, Oslo, September 1976,” mortality is considerably more concrete and immediate. Although the poem is tinged with some humor in the poet’s dreamt conversation with his dying father, it turns somber towards the end:

Art is an ever-present theme in Harding’s work, and thanks to his background, the poems engage not only with poetry but with music, painting, sculpture, and the lives of various artists. Harding’s deep connection with various genres of music emerges in many poems in this collection. One can spot it in poems such as “Europe—A Winter Journey,” “Davenport Blues,” “Danny’s Dream,” “Für Elise,” and “The Flute Player.” In “Winter Tour,” the poet moves from depiction of a cold winter day when even “the shining lake of summer has shrunk to a traffic mirror” to an evening immersed in jazz.

The beginning of “Persephone,” a poem inspired in part by a Magritte painting, illustrates the precision of Harding’s imagery:

Color symbols add richness to “Rugosa Roses,” with its sexual undertones:

Again at the end of the poem, when the couple muse over their stay in the house, the color symbols turn into sensual images:

Harding’s fascination with painting is evident in many of his poems. “Painting has also meant a great deal to me,” says the poet in a preface. “At one time that was really what I wanted to devote myself to.” This urge is sometimes stronger than the urge to write poems, as the poet remarks with disarming (or defensive) humor in “Watercolors.” He steps into a river and sees the beautiful reflection of blue sky, the mountains, and the landscape nearby.

The underlying anxiety evident here about quality in art and in particular in painting crops up in other poems, like “1958 (Miss Setterdahl’s Art School)” and “Imperfect Tense,” from Harding’s sequence about Dante Gabriel Rossetti:

In the brilliant title poem of this selection, “Guarding the Air,” contemplations of art slowly evolve into a somber philosophical musing on the way we live and how we can change to find the right path. The poem starts with these arresting lines:

This grand poem, which has a circular pattern, is replete with images and speaks about unexpected correspondences in the urban space, our somnambulistic existence, freedom, love, and the innocence of childhood.

This poem demonstrates that Harding is a visual poet of the highest order. His poems are rainbows of colors that acquire symbolic meanings dependent on their themes and their contexts. This is understandable, since he started out as a painter. Harding says as much in a preface: “I’ve never been ashamed of the visual qualities in my poetry, even though they have never been in fashion during the whole time I’ve been writing. Because at a certain time in my youth I took the step over to poetry from painting, I have always regarded the poetic image as central.”

That the poetic image is central means it is not there for its own sake: Harding’s poetry explores many themes of everyday life that engage the heart and the mind of the reader. His poetry is thus a rare combination of beauty and intellect. There are lines in almost all the poems that made me pause, ponder, and move forward, such as these from “The Star-diver,” one of the finest poems in this selection:

“The Star-diver” is a magnum opus on our identity and alienation, on disorder and the void that surrounds us. The poem pulls the reader into its magical canvas, thanks to the translation’s fluid grace.

Roger Greenwald deserves thanks for making the gift of this book to serious poetry readers across the globe. These translations of Gunnar Harding’s poems are so pellucid that I can only agree with an advance comment by the American poet Kenneth Koch, who wrote: “It is hard to believe these poems are translations — they are so clear, so exhilarating, have such immediate and uninterrupted effect.”

Guarding the Air proves beyond doubt that Gunnar Harding is a modern poet with a distinctive stamp of his own. Steeped in broad cross-cultural influences, Harding has masterfully crafted vision and music into free verse. His integration of literary and artistic traditions into imaginative creations of broad scope allows us to experience a new realm of poetry that is accessible, reflective, and rich with depth and inventiveness.

Gunnar Harding (Author, Photo by Paula Tranströmer) and Roger Greenwald (Translator and Editor)

16-Nov-2014

More by : P. G. R. Nair